A fantastic new resource has been published – an Agriculture Atlas. This is a really useful introductory to agri-food and rural policy in the EU, and mostly revolves around how CAP is implemented, including in a number of member states. ARC2020 has an article on Pillar 2, written by Helene Schulze and Oliver Moore. Below we feature this article, which we are also featuring as part of this rural dialogues series, as it explains how CAP relates to rural development. Published by Heinrich Boll Stiftung, Birdlife International (Europe and Central Asia) and Friends of the Earth Europe.

Download the Agriculture Atlas: Agriculture Atlas 2019

The Common Agricultural Policy has two “pillars”, or pots of money to draw from. Pillar I, which consists largely of direct payments to farmers according to the area they manage, has come in for a lot of criticism. Pillar II, which supports rural development policy, is seen as more useful. But as the agriculture budget shrinks, it is Pillar II that faces the bigger cuts.

The Common Agricultural Policy is not just about farming. Its second Pillar aims to promote “good practice”, such as cooperation among producers and environment-friendly, climate-resilient farming methods. This “public money for public goods” approach is what distinguishes Pillar II from Pillar I. It is why Pillar II is widely regarded as the socially and environmentally ambitious part of the EU’s farm policy.

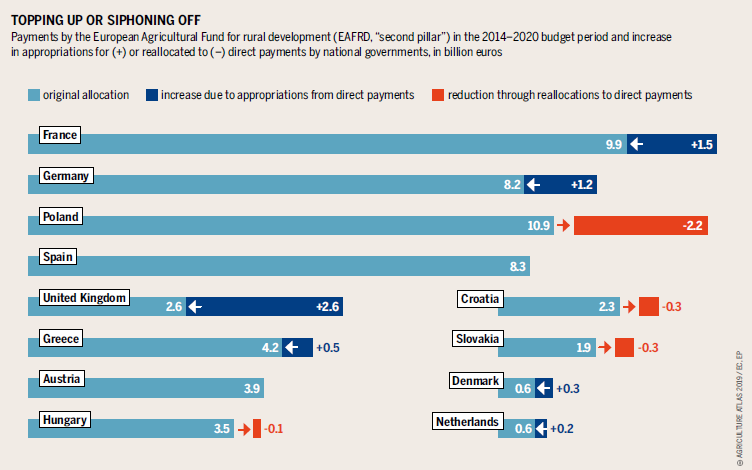

Of the total agricultural budget of €409 billion in 2014–20, less than one-quarter, or €100 billion, was allocated to Pillar II. Co-financing by national governments bumped that up to €161 billion. How effective this money is at promoting sustainable rural development depends on the programmes that the national governments choose to support, and how much of their Common Agricultural Policy budget they allocate to it. Austria devotes 44 percent of its combined pot to Pillar II; France allocates a mere 17 percent. That means that Pillar II overall has had mixed results.

Pillar II is currently supposed to pursue three goals: competitiveness, sustainability and climate action, and regionally balanced development. These overarching priorities translate into six priority areas: knowledge transfer and innovation; farm viability and competitiveness; food chain organization, animal welfare and risk management; ecosystem conservation; climate mitigation and resilient agriculture and forestry; and economic development of rural areas.

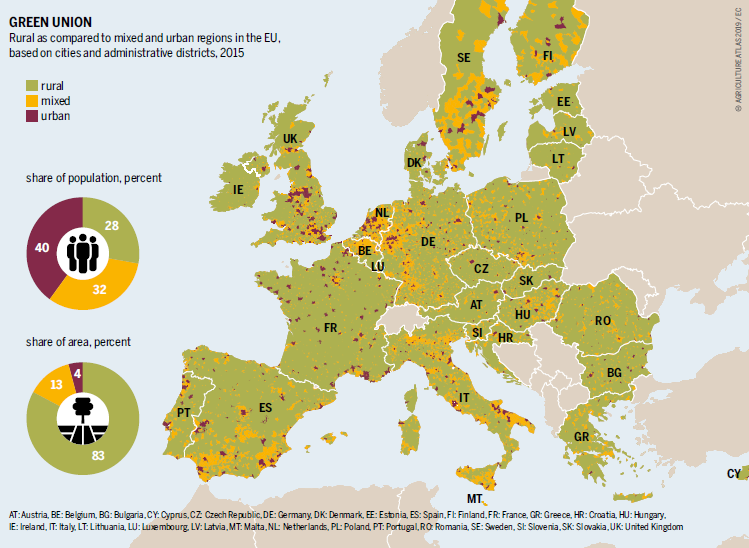

One-fifth of the EU’s population lives in rural areas. These are highly diverse, so Pillar II’s flexible approach makes sense when drawing up programmes to suit local needs. It allows national and regional governments to pick and choose among an extensive menu of options, including for example start-up aid for young farmers, support for tree-planting, and funds to deal with natural disasters. The most frequent measures are physical investment, agri-environment-climate measures, and support for areas facing natural constraints such as difficult climatic conditions, steep slopes, or soil quality. The measures chosen must relate to the three overarching goals. For example, organic farming ticks all three boxes: it contributes to competitiveness, supports environmental sustainability, and helps develop the countryside.

Each government chooses a different approach. Ireland, for example, supports organic farming because it contributes to biodiversity, water management (including fertilizer and pesticide management), soil, resource efficiency and carbon conservation and sequestration. All these relate to Pillar II’s environment and climate goals. Lithuania, with more than 40 percent of its population in the countryside but an ageing farm population, promotes modernization and economic support of small and medium-sized farms that struggle to compete in the European market. It also encourages job creation, rural area and business development, and environmental measures. In the Netherlands, just 0.6% of the total population is classified as rural. The government’s Pillar II funding focuses on stimulating innovation and environmental sustainability of its intensive, specialized and export-oriented farming industry.

Despite differences among countries, Europe shares some major trends and challenges. Rural areas are emptying out, and the people remaining there tend to be older. Young farmers are uncommon; prospective farmers find it difficult to acquire their own land. Small and medium-sized farms are being lost as big farms get bigger. Digital services are poor. A key task of Pillar II is to address such problems.

At least 30% of EU funds under Pillar II have to be directed toward environment and climate goals. This Pillar is the only part of the Common Agricultural Policy that seriously deals with issues such as soil, water and air quality, animal welfare, biodiversity conservation, environmental protection and climate resilience.

Current proposals call for the Pillar II budget to be cut by as much as 28 percent. In part this is to maintain direct payments to farmers in face of an overall drop in funding for agriculture. This has caused an outcry: Pillar II is widely regarded as the part of the Common Agricultural Policy that does the most good because it can be tailored to local needs and supports the public interest rather than giving handouts to individual farms or businesses. If Europe intends to focus on the many social, economic and environmental issues facing rural communities and shift towards climate-resilient agriculture, the second pillar must be protected.

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.