Somewhere between convenience, efficiency, cost saving and a comprehensive EU surveillance mega state, the use of drones and other in-the-sky technologies for ensuring CAP compliance represents, as it were, a Brave New World. By Helene Schulze unpacks the details.

Imagine annual farm audits performed not by EU regulators pacing the fields and talking through the details with farmers but by gently buzzing machines flying overhead, measuring, photographing, assessing compliance to CAP rules and regulations. Whether this image inspires excitement or apprehension has divided opinion in Europe. How have AgTech tools like satellite mapping, remote sensing and drones been implemented in measuring CAP compliance? What are the concerns?

The EU spends almost half of its annual budget on agricultural subsidies, around €59 billion a year. These subsidies are allocated on a two-pillar basis; the first, a basic payment per hectare of agricultural land and the second funds based on voluntary agri-environmental service provision. A form of compensation for farmers, they encourage the maintenance of hedge rows, buffer strips and meadows, the limitation of fertiliser use and adherence to crop rotation plans, for example.

With such vast spending comes the necessity to ensure taxpayer funds are allocated fairly and accurately. High-tech data collection devices such as satellite mapping and drones are a way of doing this. Ray Purdy, Senior Research Fellow in environmental law at the University of Oxford, told me ‘almost all EU countries now use satellite technology, which can produce accurate maps of the size of agricultural parcels (ensuring farmers are only claiming subsidies for genuine farmland), and to check if claimants are complying with certain environmental conditions attached to subsidies.’

Since 1988, the Monitoring of Agriculture and Remote Sensing (MARS) programme has used satellite mapping to measure CAP compliance. Adherence assessment is the responsibility of each member state which must establish a paying agency to perform checks and audits. EU law stipulates that each year at least 5% of all farms must be audited.

In 2012, around 70% of these required inspections performed by satellites, Purdy notes. Primarily, this is a money-saving strategy: satellites are able to cover vast swathes of land in little time. Satellite monitoring a farm costs around a third the price of sending a regulator.

Additionally, Purdy said when queried, ‘they can make farmers happier, if they provide a level playing field i.e. if they know there is less chance of others breaking the law, they don’t have to because they’re not being put in a disadvantageous competitive position.’

As mentioned in a previous Arc2020 article, AgTech hardware is being employed by many farmers across the continent as part of their own farm management strategies. The European Commission supports these efforts, arguing that ‘technological development and digitisation make possible big leaps in resource efficiency enhancing an environment and climate smart agriculture, which reduce the environment-/climate impact of farming, increase resilience and soil health and decrease costs for farmers.’

However, farms that tend to incorporate such AgTech tools currently are large agri-businesses. I asked Chris Henderson from NGO Practical Action about this scale and affordability issue: ‘new hardware such as drones and robots are unlikely to be within the financial reach of smallholders…they are more likely to find application in high-potential commercial areas with better off farmers. One thing that needs careful consideration at the macro level is the negative effects intensive agriculture (driven by new technologies) might have on the poor – perhaps displacing them from their land or out-competing with them for water.’

This points to a divergence in access and response to AgTech. Perhaps, if farmers are not employing drones, robots and satellite imagery on their own land, they may appear more critical of auditing bodies doing the same. Since member states are responsible for their own compliance assessments, there has been some variance in the types of technologies and strategies of inspection, as well as responses to these across the continent. A 2008 study by Ray Purdy found that a third of farmers were opposed to satellite monitoring in the UK, where it has been used to combat subsidy fraud for over a decade. In his interviews with farmers Purdy found that many ‘made reference to ‘1984’ and ‘Big Brother’ and were concerned that the satellite would be ‘peeping’ or ‘spying’ on them.’

These are natural concerns. For one, with a human inspector one at least knows when the assessment is taking place whereas satellite monitoring gives no such indication. Farmers are unaware when they are undergoing an inspection. There are also questions to be raised about who has access to the collected data. This is powerful information, information which could give some farmers a competitive advantage. With the potential implementation of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in CAP compliance testing, these concerns are heightened further. Drones can get a lot closer to the target, taking sharper photographs. Farms are also homes on private land and such inspection could be very intrusive. Whilst UAVs are being explored in the agricultural context and there are pilot projects across Europe, they have yet to be included in CAP monitoring.

When queried, Vicki Hird, food and farming policy coordinator at Sustain, argued that ‘there’s certainly a lot of potential here both in measuring compliance but also from the perspective of the farmers and workers as part of a sustainable farming strategy to assess needs and review progress on land. It can help bring the whole farming community into understanding about how nature and farming should work together on a whole farm basis.’ So, AgTech tools must be incorporated into other governance and management strategies which bring people together rather than alienate them which would risk farmers feeling observed from a distant, invisible body reading to subject penalties.

Purdy reiterates this call for the maintenance of human interaction in farm auditing; ‘if a machine is doing the monitoring it provides less contact between the farmer and the regulator, which might also be an opportunity to discuss other farming issues. Sometimes human contact can be important.’

Irrespective of these fears, CAP auditing will likely become only more technology-dominated in the years to come. Key is to consider in which frameworks such technology can be used to support farmers and prevent feelings of alienation and constant surveillance. Theoretically if collected data were made publicly available, small farmers could begin to benefit from AgTech developments currently too expensive for their own use. Through open-source initiatives, they could have access to information about their land currently only accessible to wealthy agri-businesses. It is also possible to collectively own and manage technologies, as the extensive CUMA machinery co-ops in France show. Again, for this to work these developments must be thought through thoroughly in consultation with farmers. Moreover, the delivery of any such tech should involve farmers – not so much as inspected from the sky, but, rather, as participants in the process of verifying their own management techniques.

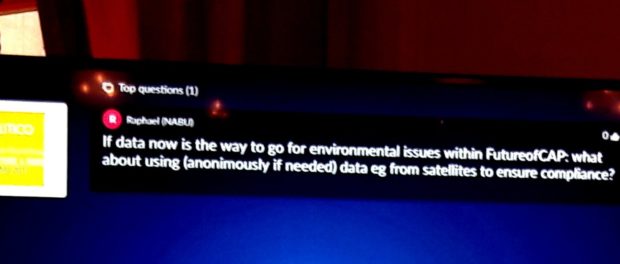

It is also interesting to explore how these technologies might impact the relationships between companies, environmental NGOs, regulators and farmers: if Bayer sound more farmer-concerned than NABU, as the example from the politico event referenced in the image above suggests, we are in strange territory. And if farmers are ignored it is unlikely that such auditing technologies will receive widespread support in a climate of concern over an increasingly intrusive surveillance state.

More

Future of CAP: Robots in the field? (European Commission)

How Copernicus is paving the way for the future of the CAP and Farming 2.0