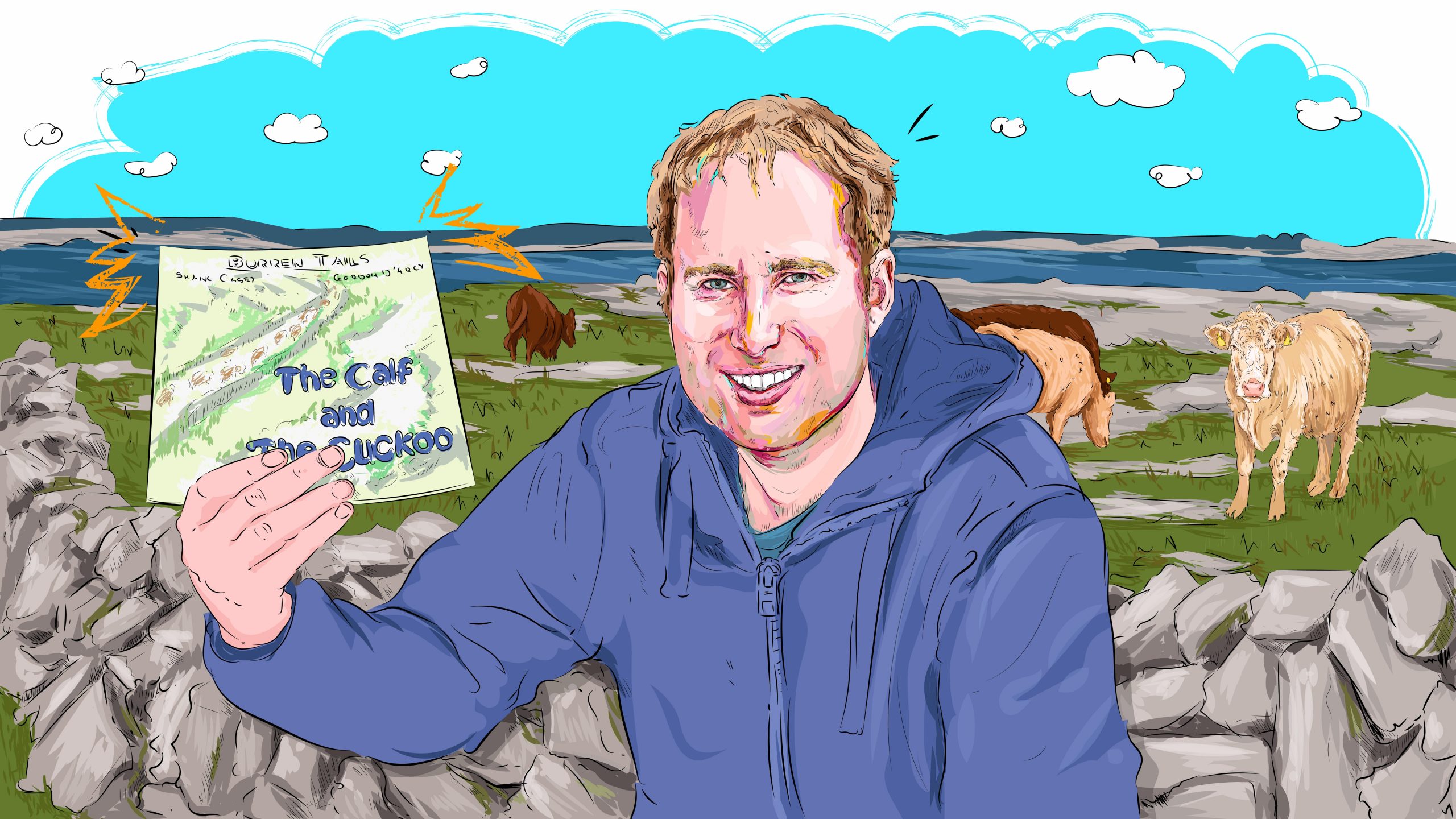

We’re back on Shane Casey’s farm in The Burren, Co. Clare, Ireland, where he has another busy spring of lambing and calving behind him. There’s only so much you can do to prepare – after that, it’s a question of watching carefully for the telltale signs in the ewes and cows. Shane’s father was an early adopter of livestream technology that makes the night watch a little easier. But successful lambing and calving depends on the farmer’s expertise as well as patience. Knowing if and when to intervene, whether to call the vet, and how to help the newborns find their feet.

It was another busy Spring on our farm – it always is!

Like every year, it began with some preparations. The shed, which housed calves for a few weeks after weaning in late Autumn/ early Winter, had to be cleaned out, disinfected, and bedded with clean straw before the ewes could be moved in for lambing, with fresh hay, concentrates and clean water at the ready.

Then there was a trip to the vets to pick up some tubs of powdered colostrum, in case, for any reason, a ewe didn’t produce enough of her own or had triplets, and some iodine spray for navels. After that, there were tags for ears, rings for tails, and paperwork to have ready as well. Then it was a waiting game.

Watching ewes to lamb takes patience

The Suffolk ewes always lamb first, as the ram lambs need to be strong enough by Summer for breeding. Then the Texel ewes, and finally the Galway ewes – their ram lambs won’t be sold for breeding until they are a year and a half, so mid-season lambing is fine.

Lambs can arrive at any time of the day or night, but luckily, we have a camera installed in the shed that allows us to monitor a live feed of the ewes from the comfort of the house at night – a technology embracing approach to farming that my father installed in the early 1990s, that may have been considered advanced at the time, but a far cry from our dependence on technology in 2022!

Watching ewes to lamb takes patience – a lot of it. An occasional glance is not enough when watching a pen of around twenty-five ewes that could lamb at any minute (there are plenty of farmers who have to watch multiples of that number, so I’m not complaining).

Spotting the tell-tale signs of restlessness, rising and lying, scratching and sniffing is important. A ewe could be ‘sick’ for a while and then lamb very suddenly, and a lamb (or the ewe herself) could be lost in minutes if something goes awry. And at the same time, intervening too early can also cause complications. That’s where experience (and even more patience) comes into play, but I was also lucky to have a good teacher to learn from.

The Suffolk and Texel ewes tend to need help more so than the Galway ewes. When you do make that decision to intervene, you’re hoping that the lambs hooves are pointing up and not down (the latter usually means the lamb is coming backwards), that two legs are coming and they both belong to the same lamb (sometimes twins will try to come out at the same time!), and the head is already past the narrow part of the pelvis. Then it’s just a gentle effort to help the ewe along.

Once out on the ground, a quick blow in the lamb’s ear usually gets a shake of the head and you know it’s okay. Every sheep farmer has their own tricks for this – a splash of water, some straw to tickle their nose, or a quick swing of the back legs to check the lungs are clear. But things don’t always run smoothly, and this year we had to get the assistance of the vet a couple of times – once to perform a caesarean section.

After lambing, you want to get the ewe and lambs into a pen on their own, before the lambs stand up and start wobbling off, or another ewe starts mothering them. This is particularly important with the hoggets (first time mothers) who may not yet have developed their maternal instincts.

After an hour or so you’ll want to check that the lambs have sucked, and if not, then you need to help them. If they don’t get that first feed, the colostrum or beastings, early on, they’ll get weak, and will need a lot of help to recover, if they ever do at all. And once that first ewe has lambed, you want them all to lamb in quick succession, particularly if there is a need for fostering lambs to different ewes (and avoid suck lambs if at all possible!).

Till the cows come home

While all this is going on, we still have to keep an eye on the cows in the winterage. They’re in good condition after a mild winter, and are starting to spring (their udders are starting to fill). As the lambing hits the midway mark, the first of the cows are brought home to calf. And here again, the preparations begin.

The calving rope and jack are left in a safe place, along with iodine spray, so you’re not looking for them in the dark – the cows are all calved outside with only a handheld flashlamp and the moon providing light. A few milk cartons of beastings are collected from a neighbouring dairy farm and frozen just in case. Dehorners, tags, DNA samples, vaccinations, and paperwork will all be needed as well in due course.

Most of the cows will calf around the same time every year, and are brought to an area close to our house that we call Tra na Gan (a field of limestone pavement about 50 acres on one side of the main road and about 80 acres on the other side) about two weeks before they are due, where they get round bales of haylage to supplement grazing. This area acts as a staging post before they are brought to the paddocks around the house a few days before they calf.

Then it’s back to the waiting game, and watching for the bones (hips) to be down, and a similar restless behaviour to that of the ewes, though typically more noticeable. Patience and experience again are pivotal, and this year, due to the condition of the cows, the calves were big and needed assistance, including the vet on a few occasions.

Thankfully though, it was a relatively dry March and April which helped the calves to thrive. In other years, when the weather is wet, it leads to the spread of scour and other ailments, and calves tend to be more sluggish. This year, it was a joy to watch them find their feet in the warm Spring sunshine.

More letters from the farm

Letter From The Farm | Health, Husbandry & High Quality Meat

Letter From The Farm | Learning from a Campesino Family in Cuba

Letter From The Farm | Cresting the Peaks of Constant Change