In Cuba, food security is still a challenge after years of wars to fight against colonialism, imperialism and climate change. Yet, the island is far beyond the European Green Deal objectives, having largely achieved most of the Farm to Fork and Biodiversity targets that the EU aspires to attain by 2030. One Cuban farm is going even further. Welcome to La Finca del Medio, a 13.42-hectare family farm located in central Cuba, which is championing food sovereignty in the agroecological way. Matteo Metta writes from the farm.

In May I had the honour to visit La Finca del Medio, in a country recovering from the socio-economic hardship of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The whole family farm, led by José Antonio Casimiro González, is a rare example of a truly circular, autonomous, and agroecological system. Gastronomy, rural development, renewable energy, biology and nature are holistically and harmoniously connected with farming.

With global food security at stake after the energy and feed import crisis, what can we learn from this farm and how can we incorporate agroecology in the future post-war and post-growth European Green Deal? Here some recollections and reflections from my visit.

Beyond the gates, beyond the claims

Although there are many videos, articles, and blogs available online about this farm, my preliminary knowledge about ‘La Finca del Medio’ was basic enough to mark an unexpected discovery. “Remember, we’re at Km 349 of the National Freeway, Sancti Spiritus Province”, Leidy Casimiro texted me, the first Cuban woman PhD graduate in agroecology, confirming the two nights at their farm.

On the road: no signs, no commercial promotions. Leidy was not there at the time of the arrival but, at the farm gates, her sister Chavely welcomed me to the farm. Before leaving me to prepare a fresh juice from their own sugar cane with a touch of blood orange, she briefly introduced the farm, their anti-hurricane housing system inspired by traditional sandstorm-proofed households in Ethiopia, and the rest of the family: Lorenzo, little Amanda, her brother José Antonio Junior, and finally her parents Mileidy and José Antonio.

“We could have put big banners and billboards to advertise our farm with many catchy names like agroecology, agritourism, slow food, etc., but we decided not to do so. Yet, in more than 20 years, our farm has hosted thousands of people from Asia to Europe, Africa and America. They are researchers, government officials, farmers, families, activists, or simply people who want to see another way of living and farming,” explains José Antonio Casimiro González, father and initiator of the family farm.

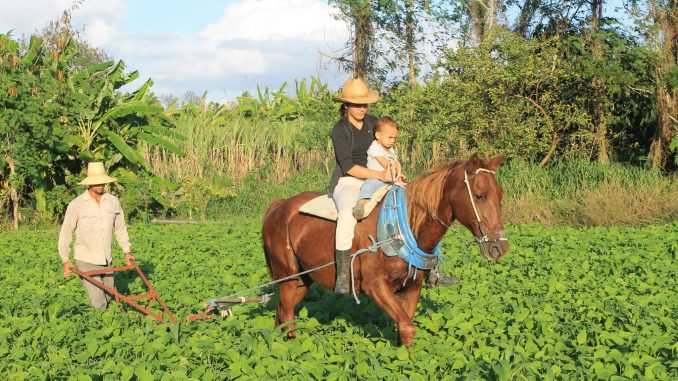

Everyone in the family is involved in the farm labour, including farming, fishing, food processing and delivery, energy production, organic nutrient management, housekeeping, cooking, hosting and so forth. The farm is composed of a mix of plants and animals. “Everything here is connected and functioning like a living organism. In 13.46 hectares, we have around 30 animals, including cows, horses, oxen. We do also have chicken, and pigs, and all without buying external feed. We produce a large variety of plant-based food in a rotational system, from horticultural products, corn, rice, sugar, yucca, potatoes. Part of our agricultural production is sold to the State to meet our minimum quotas, whereas the rest is used to feed ourselves and our visitors.”

The family as agroecological architects of the farm

According to Antonio, an agroecological system can be built only after many years of observing and adapting the interrelations existing in the farm, the nature, the family, and among them. “Over our 20 years in this farm, we had to drop out some elements, like goats or wild turkey because they were altering our equilibrium by over-eating our plant-based food (rice, vegetables, yucca). What you see here, today, is the result of a long-term observation and selection made and led by us, to adapt seeds, breeds, plants, and techniques that meet our specific conditions. Living in a farm today means combining scientific theory with practical observations, such as studying how water, minerals, organic matter, birds, insects, plants and animals interacts in a complex system and finding ways to regulate them for our family life.” In total, a diversity of trees was established along 5 km, both at the edges and inside the farm, intercropped with pineapples (Bromelia pinguin L.), mulberries, guavas and banana trees, without a predefined order.

Nourishing with ‘campesinos-agroecologia-gourmet’ food

At midday, I had the pleasure to sit down and have lunch with the whole family. It happened to be Mother’s Day in Cuba. The table was decked with a variety of farm products cooked by Chavely and her mom, Mileidy. Little Amanda was also there, always trying to help her mom and put her hands into the art of cooking.

Antonio talked before Chavely and Mileidy presented the dishes. “It is not because one adopts a single green practice like vermiculture or composting that we can claim to be agroecological. We cannot talk about agroecology if we do not find enjoyment and genuine nutrients in our own food. We cannot talk about agroecology if women’s labour is not as equally valued as men’s. There will not be agroecology if the family has no harmony and pleasure to live in deep connection with and on the farm.”

In a country which still imports the majority of its food from abroad, La Finca del Medio produces its own milk, butter, yogurt, cheese, meat, eggs, flour, beans, honey, sugar, coffee, corn, fruits, and plenty of vegetables like tomatoes and lettuce. In a country experiencing poverty but no misery, La Finca del Medio lives prosperously in a state of nature abundancy and zero km food. Antonio explained how, once, he impressed Carlo Petrini (Slow Food founder) with his example of “zero instead of max 20 km distance” to reduce the slow food miles from farm to fork.

“At the end of the day, what’s the point when organic farmers or agritourism farms cannot eat their own food or propose it to their guests, consumers, and visitors? How can agritourisms sell a farm experience without giving their own products to their guests? What is the point if food is organically produced but without campesinos and without the fresh taste of genuine ingredients? Here at La Finca, we produce food that is campesino-agroecological-gourmet.”

Food security through agroecology? Yes, with more campesinos in Cuba

On my second day, I posed Antonio a provocative question: “Do you think agroecology should and can feed Cuba?” Rather than a straightforward answer, I was expecting a critical reflection on my own question. Antonio gave me a humorous answer: “Yes, we can feed the world and live like the American dream, but we need at least five planets.”

Personally, I often think society and politicians expect agroecology to meet the growing demands from an urbanised, consumerist society without firstly questioning the norms and values behind our own footprint, consumptions, and lifestyles. Antonio believes that there is something intrinsically wrong when agroecology is compared to other farming systems like precision agriculture on the basis of simplistic metrics like food productivity. “Give us a metric that considers healthy food without chemicals and preservatives, give us a metric that considers gender and rural employment, give us a metric that considers biodiversity, and agroecology will be the champion of this league.”

And not only. At the time of my visit to the farm, I was reading several books in parallel about the history of Cuba, its effects on agriculture, and the number of agricultural reforms that followed after the 1959 revolution until 2017. There are issues of food security that are deeply intertwined with history, land, people, climate, urban planning, energy, currency, technology, and yes, geopolitics. Often, we narrow our focus on this or that particular farming method to answer more complex questions.

Antonio recalled: “In Cuba, there are five people in rural areas to feed 25 people living and working in urban centres. For years, the world has created income inequalities draining young, intelligent, hard-working people out from the rural areas. Just to add that every time, we talk about food security first, and food quality later, as a secondary aspect. I believe we need to re-consider the supremacy of food quality if we want to aim towards a healthy society. If we want to help Cuba, we need to help people and farmers to live and work in Cuban rural areas.”

Circular bio-economy as peasant autonomy

One of the things that impressed me when visiting this farm was the use of terminologies and practices which circulate quite highly in the European green growth narrative and farm modernisation projects. However, in La Finca del Medio, things like agroecology, circular economy, biodiversity protection, renewable energy, gender equality were as they truly are. Behind these ‘labels’, nothing was hidden like new forms of fossil-fuel dependencies of ‘clean’ technologies, financial indebtedness, green productivism, land grabbing, water over-extraction, technological monopoly, monoculture, and farmers’ alienation.

In my mind, La Finca del Medio was somehow ticking many sustainability boxes, but also setting higher ethical and development standards for a climate-neutral agriculture embedded in the rural development. “We try to use our own resources as possible, while maintaining our small scale and valorising our own family work. We pump our water thanks to this small windmill. We source our energy from the national electricity grids too, but we rely largely on those solar panels and small wind turbines. We have a small tractor for exceptional uses, but we bought it only because we are able to maintain or repair it by ourselves. Otherwise, we go to the village and do work the land largely by using our own animals.”

Antonio adds: “We select, store, save our own seeds. We cook our food by using our own small-scale biogas digester and wood. We feed our plants through our own organic minerals and fertilisers, mostly coming from our livestock manure. We feed our pigs with our agriculture outputs (e.g. yucca) and food by-products (e.g. fish bones). Our cows are free to graze. They eat grass and sometimes yucca or additional minerals.”

What can we learn from La Finca del Medio?

Just after my return to Europe, I was lucky enough to visit another example of an organic farm in the north-west of Denmark. 100 dairy cows, 500 hectares of rotating crops and grassland, a long-term bank loan. In the pipeline, a new investment project to install a biogas digester to close the energy circle, while selling organic milk to Copenhagen and producing their own whisky sold all over the country. The differences with La Finca del Medio were more than a matter of scale. Indeed, I was confronted with two types of agricultural pathways: agroecology vs modernisation.

With the obsession to become climate-friendly and greener, the (European) modernisation pathway can miss several underlying nuances which make our agricultural development truly sustainable.

Firstly, we need to tackle the broader inequalities between rural and urban areas, which alter the demographics, income balances, food demands, and living conditions. To farm holistically with nature and reduce the environmental footprint from farm to fork, rural areas need to provide attractive living conditions for young people and families to stay, move, and come back. At the same time, we need to direct farms towards investments that integrate their farming systems and livelihoods with the rest of the territory (e.g. agritourism, bakeries, restaurants, schools, sport, music and art centres).

Secondly, a just & green deal cannot underestimate the concentration in ownership and control of the means of production. For instance, bio-economy or circular economy – while they might be more energy efficient – can still recreate (often publicly supported) monopolistic projects in which single farmers can set the conditions for rural and agricultural development in a given territory (e.g. price, types of crops, farming method). This can be an issue also for the diversity of our seeds, land use, and technologies in general. More collective work is needed to reach economies of scale in agriculture, while maintaining the small-scale farmers’ autonomy that make rural areas thrive.

Thirdly, we need to valorise the holistic intelligence of agroecological farmers before the smartification of specific skills and operations. La Finca del Medio shows how the family farm built long-term complex knowledge based on the everyday observation of nature-farming-climate-family relationships. In one single day, I saw Lorenzo performing a vast array of farming tasks (e.g. milking, feeding, fishing, food processing, fruit harvesting, ox ploughing), all integrated within the climate, nature, and family conditions.

As the (digital and green) modernisation of European farming continues to put pressure on ecology and family farms, as well as moving agriculture increasingly towards data-driven, fossil-fuel based, delegated tasks, we need to raise macro-level questions on smart farming: are we getting rid of chemical pesticides and antibiotics from our food? Is farming and land becoming accessible for young people? Are we enabling farm decisions to be independent from commercial technologies and interests? Are we strengthening farmers’ capacity to execute multiple tasks without compromising the diversity in agriculture and the connections with rural areas?

Fourthly, agroecological farmers can adapt digitalisation to their own needs and possibilities. In La Finca del Medio, internet connectivity and social media served different functions. In my short stay, I saw digitalisation being deployed for the interactions with visitors, the sharing of the farm stories, the search and acquisition of information like events, market prices, and products. As Antonio said: “Digitalisation can be a great opportunity for the campesinos if we use it to enhance instead of replace our unique position in nature, food economy, and community.” Interestingly, in this farm, the digital interactions with visitors and management of social media were supervised by one person, Leidy. As a young, university-educated woman, digitalisation allows her to pursue some research activities away from the farm, while deploying her skills to support the family in new digital tasks. This case, like many other examples in Europe, calls attention to the gender and age divisions of digital labour in agricultural holdings or family farms.

Many more aspects have not been highlighted in La Finca del Medio like the high number of birds populating the farm; the risk management strategy envisaged by the family against climate adverse events (hurricane); or the high volume of food production per family working units.

La Finca del Medio shows how the climate objectives and emission reduction mechanisms of the European Green Deal can fail to prioritise support towards these kind of agroecological farms in Europe, or even add more competitive pressure to their survival. There are many ways to support farms like these. For instance, instead of concentrating agricultural subsidies into large farms or investing billions in the military industry to secure geopolitical control over fossil fuels and raw commodities (grains or feed), the European Union should invest in public assets and networks that make agroecology easier and viable for small-scale family farms and young people who want to live and work in rural areas.

Leidy Casimiro’s doctoral thesis, ‘Methodological bases for the socio-ecological resilience of family farms in Cuba’, is available here

More letters from the farm

Letter From The Farm | Cresting the Peaks of Constant Change

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.