‘Should agricultural subsidies go to labour not land?’ This question was up for discussion at a meeting hosted by ARC2020 in Summer 2021. Area based payments are absolutely central to the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) yet they have a range of negative impacts and act as a barrier to progressive change. In search of a fairer, greener and rural-proofed subsidy system to support the farming community (including farmers and farm workers) and to promote mainstream adoption of sustainable farming practices, ARC2020 wants to reignite the debate on whether the CAP should support labour rather than land. Here, Matteo Metta introduces the current state of play in EU agricultural income support and makes the case for a more attractive and substantial Small Farmers Scheme. This is an extract from our report ‘Should agricultural subsidies go to labour not land?’. The full report is available to download below.

Download the ARC2020 Labour-Based Subsidies Report

Farm labour vs farm income

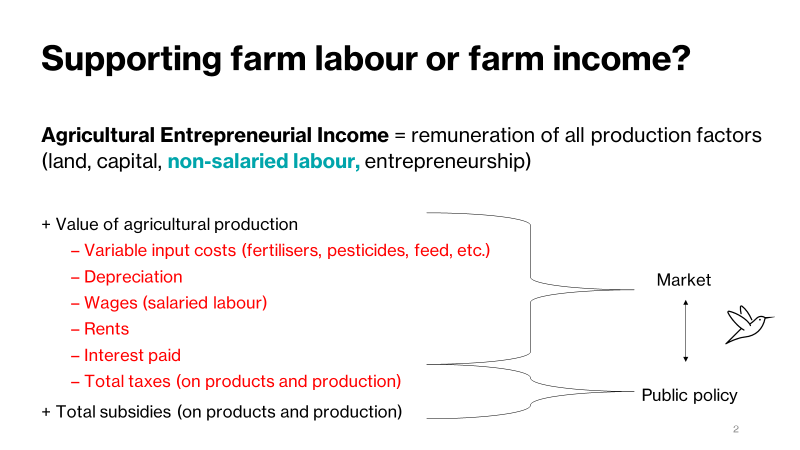

The Agricultural Entrepreneurial Income is an important context indicator used by the European Commission to explain the need for agricultural income support, as well as the decline in farm numbers. It tells us how much a farmer earns as remuneration of all the production factors — land, non-salaried labour, capital and entrepreneurship. Labour is just one of the variables that can affect farm income. The market and public policies (within ecological and environmental boundaries) strongly affect farm income.

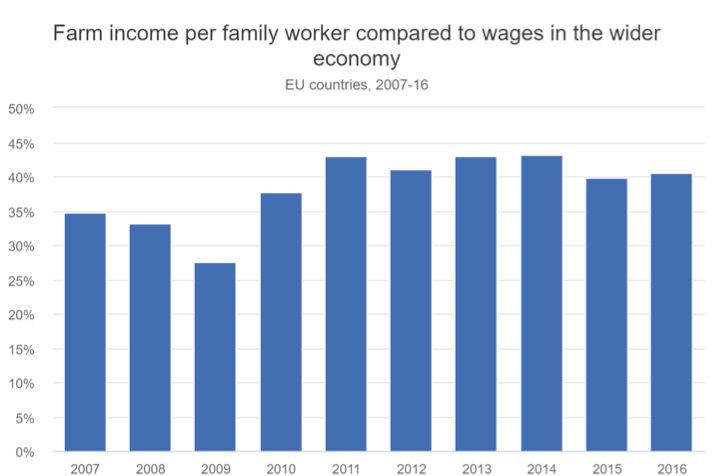

Comparing Agricultural Entrepreneurial Income with other wages in the wider economy is an important indication of how agriculture is doing across the EU over time.

The graph shows how farm income compares to other wages in the wider economy. At the low point in 2009, farmers earned about 27% of the EU average wage. In 2011 farmers earned 42.5% of the EU average wage. The DG AGRI data shows that farmers earn much less than the average income. However, the Agricultural Entrepreneurial Income indicator does not take account of income that farmers earn from other sources, like off-farm employment from non-agricultural activities, remuneration, social benefits, income from property, and it is not clear whether it considers income from on-farm diversification activities (agricultural service outputs?). As such, the Agricultural Entrepreneurial Income indicator alone is somewhat limited in justifying agricultural subsidies to farmers. That is not to say that farmers should not be supported; the sector must overcome many challenges – biodiversity loss, climate change, labour violation, land concentration, inequalities in direct payments based on entitlements, rural depopulation etc – but Agricultural Entrepreneurial Income is perhaps not the most reliable tool to move agricultural policy forward.

Existing CAP interventions supporting ‘farm income’

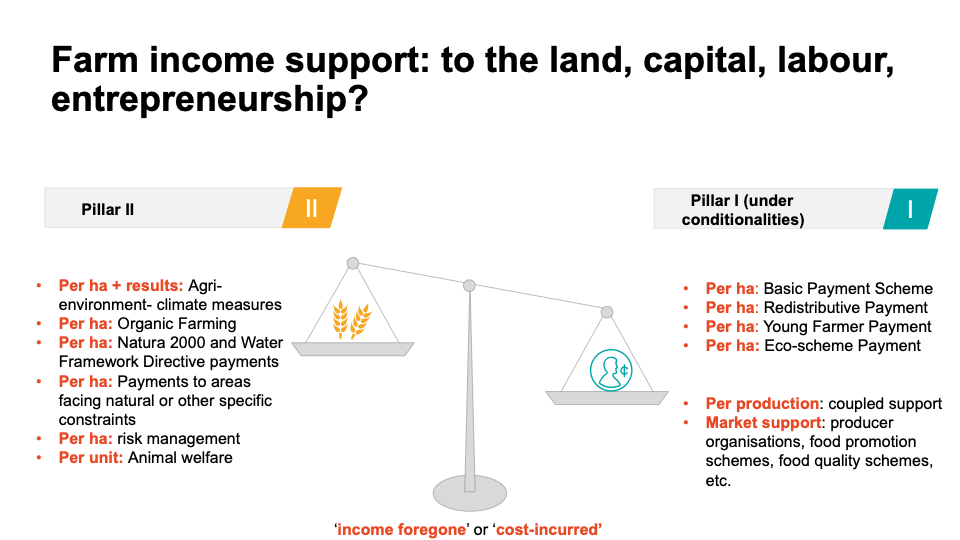

If we look at the existing delivery model, interventions supporting farm income do not necessarily go to labour – they might go to land, capital, income foregone, cost incurred, or entrepreneurship.

Instruments under Pillar I (the heaviest part of CAP) go to farm income based on conditionalities. The vast majority of payments in CAP Pillar I and II are per hectare (per ha) payments. Coupled support – an even more problematic tool if designed in a simplistic manner – is linked to production level. In the future CAP, eco-schemes, even if they are based on ‘income foregone’ and ‘cost incurred’, will still be linked to “the hectare”, thus reinforcing the legacy between the CAP and its negative side effects (e.g. land concentration, farm income inequalities).

Under Pillar II, the question arises whether payments go to the farmers and their work or to land and capital (e.g. machinery, finance). One possible exception are results-based payments which try to disconnect payments and the hectare, but so far the idea of linking labour to result-based payments has been largely overlooked, even in research and innovation projects like EIP AGRI. One example of an EIP AGRI project that does consider labour aspects and should inspire others is the Operational Group Biogemüse in Northern Hesse, Germany which created jobs for people with disabilities within a regional value chain for organic vegetables.

The ‘per-hectare’ mantra is one of the fundamental assumptions to deliver on many CAP policy objectives in a simple, efficient and effective manner. It is the basis to deliver public money in a neo-liberal policy framework. However, the rewarding of labour – which is the essential recognition of active farmers – remains tailored apart or blurred in both the environmental and climate debate, as well as in the long-dated struggles for a fairer distribution of direct payment.

Case-study: More attractive and substantial Small Farm SchemesThe CAP area-based direct payments have never benefitted small-scale, labour-intense farming systems like organic horticulture. Organic horticultural producers are generally small scale (even below 0.5 hectares), full time self-employed, and rely on their own work, as well as on salaried or non-salaried labour (woofers, family members, volunteers). Their produce is largely involved in seasonal, highly nutritious, short and/or direct food supply chains (e.g. food boxes, community supported agriculture, restaurants, on-farm shops). To pay back their higher environmental and labour costs, the selling price might be relatively higher compared to cheap, plastic-packaged imported food, or highly subsidised food alternatives (e.g. animal protein). There are cases where selling price is even lower than commercial ones. More importantly, these horticultural producers are often engaged in community activities, providing space for social gatherings, solidarity, cohesion, and collective learning.  Yet, the Common Agricultural Policy at EU and national level falls short, or completely neglects to provide substantial support for this important farming system, delivering a wide range of delicious products: tomatoes, lettuces, mustards, courgettes, potatoes, pumpkin and much more. Another example is the traditional olive farming in the Mediterranean countries, which have high labour requirements and specialised skills (manual pruning of traditional varieties of olive groves adapted to local conditions). As pointed out by an Irish organic horticultural producer in the North West of Ireland:

Another small-scale farmer [6 ha] in West-France (Bretagne) went in the same direction:

Certainly, the market is one of the areas that needs improvements. But the EU and the Member States have the power to design more effective and substantial Small Farmers Schemes (SFS) that go beyond the logic of ‘per hectare’ payments. A shift away from a the “higher payments to larger land-owners” needs to accommodate more labour rewarding considerations if we want to keep young people in rural areas and offer them a fair income. Currently, the EU sets a very low threshold to reward SFS under the CAP (i.e. 1250 EURO). This isn’t attractive at all if one considers the living costs in some countries like France, Ireland, the Netherlands. In a highly competitive and free market, this blind payment mechanism ‘per hectare’ does not create a common level playing field across various farming systems. With the new CAP Strategic Plans under development, the Member States can take money away from large beneficiaries with high historical entitlements and revamp this scheme to offer more attractive incentives to small farmers who want to stay on the farm and commit to deliver organic and local food. |

Download the ARC2020 Labour-Based Subsidies Report

More

Civil Society Organisations Demand Open and Ambitious Approval of CAP Plans

Auditors – Measures to Stabilise Farmer Incomes have ‘limited effect’

Quality Schemes – Who Benefits? Central America, Coffee and the EU