Can a cash-strapped EU afford to lock itself into a dysfunctional agricultural policy? In the wake of the new positions on CAP reform agreed by the Council and European Parliament last week, Sebastian Lakner unpacks some crucial elements – and finds a lack of vision, ambition and courage. A German version of this article is available here.

Can a cash-strapped EU afford to lock itself into a dysfunctional agricultural policy? In the wake of the new positions on CAP reform agreed by the Council and European Parliament last week, Sebastian Lakner unpacks some crucial elements – and finds a lack of vision, ambition and courage. A German version of this article is available here.

On Tuesday, October 20 both the Council and the European Parliament (EP) agreed their positions on the post-2020 reform of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

In the following piece I select some details of the decisions and explain why I do not see progress in the CAP towards environmental ambition, but rather a step backwards. Overall, at a European level there is a lack of a common vision for the agricultural sector in 2030. The agriculture ministers in the Council obviously could not agree on objectives and priorities within the CAP, which is why the decisions only result in the lowest common denominator and de facto “business as usual“.

Due to the lack of new objectives, agriculture ministers repeatedly fall back into the old (and dubious) narratives of “more production” and “income generation”, instead of facing the urgent environmental challenges, including declining biodiversity, ongoing climate change and unregulated nutrient flows. The same applies to the MEPs of the grand coalition of EPP, S&D and Renew Europe. But in the Parliament, at least, there was a clear contradiction from the opposition formulating an alternative vision. Overall, the question arises whether the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) in this form still makes sense at all.

In my view, the most important elements of the decisions are to be seen in four areas, which represent the guidelines for the implementation of agricultural policy in the Member States in the coming years:

1. The financial volume of environmental expenditure in the CAP

Financial decisions often play an important role in the debate, because, after all, they provide Member States with the financial means to design their policies. And one can also derive the political priorities within the agricultural policy just by analysing budget shares.

Eco-Schemes: An important issue within the debate was the question of how much the so-called ‘Eco-Schemes’ would receive (Ringfencing). Here it is worthwhile first of all to look at the instrument itself, which the member states are obliged to offer, while farmers can participate voluntarily. According to the Commission draft, ‘environmental objectives’ should be pursued. However, the Parliament has negotiated an important addition to Article 28b, which weakens the objectives of the Eco-Schemes:

Article 28b

Practices eligible for schemes for the climate, environment and animal welfare

1. The agricultural practices covered by this type of intervention shall contribute to the achievement of one or more of the specific objectives set out in points (d), (e), (f) and (i) of Article 6(1), while maintaining and enhancing the economic performance of farmers in accordance with the specific objectives set out in points (a) and (b) of Article 6(1). – Amendment of the European Parliament 20.10.2020 (emphasis added)

So, in that sense, Eco-Schemes should also be ‘compatible’ with income and competition objectives (objectives a and b in Article 6). Furthermore, the Eco-Schemes can also include objectives of animal welfare. Animal welfare is important and represents a major challenge for agriculture, however this is again another objective within Eco-Schemes. Therefore, the EP strongly violated the Tinbergen-Rule, which says that for an efficient policy design, one should employ one instrument for one objective, and not one instrument for multiple objectives. In the end, this widening will result in less funding for environmental objectives and lead to additional inefficiencies. In this respect, the purpose of Eco-Schemes has been significantly widened to include multiple objectives and, as such, softened to the point of arbitrariness.

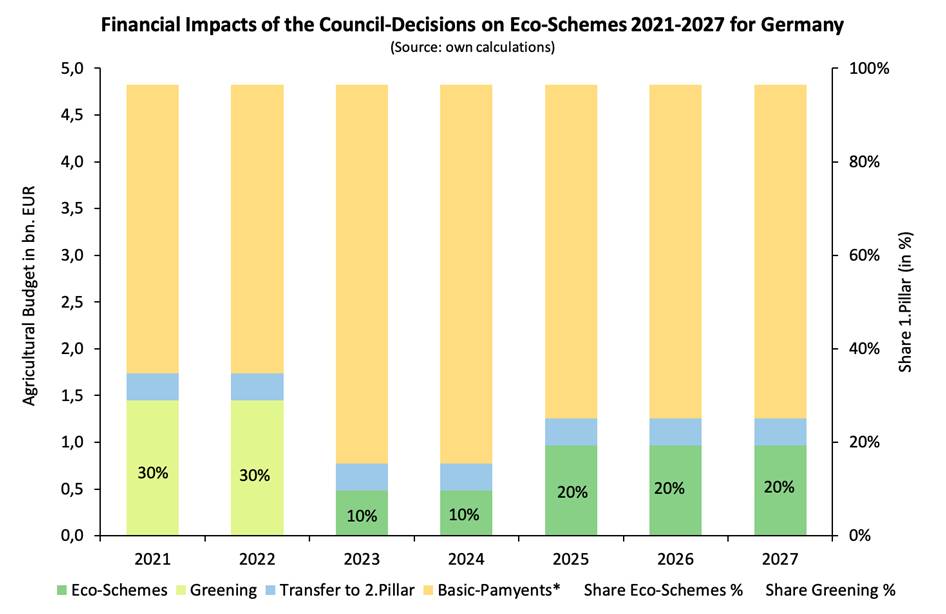

A majority of the Parliament has voted for a 30% share of direct payments, while the Council is in favor of 20% for Eco-Schemes. The Council has also decided to allow a ‘test phase’ in the first years (2023 and 2024) during which unused Eco-Scheme funds can continue to be paid out as direct payments. If one assumes, for example, that in the first two test years only 10% will be used as Eco-Schemes, a possible agricultural budget in Germany could look like this:

It should first be noted that the basic premium here still includes the young farmer premium and the first hectares, with a transfer to Pillar 2 (light blue) assumed to be 6%. It can be seen that in the years in which they are applied (2023-27), Eco-Schemes only reach an average of 16% of the Pillar 1. The two transition years 2021 and 2022 achieve much higher environmentally relevant payments at 30% via greening. In addition, the previous greening rule provided that a further 7.5% of direct payments could be reduced in the event of controls, so that de facto, i.e. from the point of view of economically rational decision-making by farmers, 37.5% of Pillar 1 was linked to environmental criteria. The 20% proposed by the Council and the 30% proposed by the Parliament are therefore rather a step backwards.

This view is, of course, subject to the content being defined. If Eco-Schemes were to be used only for effective measures, small progress could be made, but the question arises as to whether an effective design can be expected. The decisions do not oblige the member states to such a design. Furthermore, Eco-Schemes (similar to Greening) can contain substantial income components, so I do not expect this outcome of the negotiations to lead to either greater effectiveness or greater efficiency of the environmental measures under the first pillar.

The financial scope for the far more effective agri-environmental and climate measures (AECM) is also unlikely to change much. 35% of Pillar 2 is ring-fenced for AECMs, but this includes payments for Areas of Natural Constraints (ANCs). There are neither general obligations to make significantly more funds available for Pillar 2, nor will there be any new room for maneuver within the existing measures. The payments for ANCs are of major importance in this context. Contrary to the popular belief that ANCs are environmental payments, ANCs have little environmental impact. In some regions of the EU they are accompanied by environmental benefits, but this is a fortuitous effect, as ANC payments do not impose environmental requirements on farms and are in fact direct payments to certain regions.

It was initially foreseen in the draft reform that the ANC payments should be moved to Pillar 1. This was rejected by the Council, which is why the margins in Pillar 2 are not increased. Here too, financial ring-fencing is designed in such a way that the scope for effective agri-environmental measures does not increase, because other measures have now also been given minimum percentages. It may well be that the Member States are shifting priorities here too, but the room for maneuver is very narrow and, in the end, this is voluntary and remains dependent on the goodwill of EU governments.

2. The design of Eco-Schemes

Eco-Schemes were initially designed to be quite flexible. It could have been an area-specific payment for the areas on which an environmental service is actually provided. The payments could be cost-based or paid as a lump sum with a so-called income component (i.e. well above the costs of a measure).

The Parliament significantly limits this scope by prescribing the model of a payment with an income component to be paid per hectare or for the whole farm. The cost orientation has apparently been deleted. However, the payment itself may vary according to the level of ambition:

Article 28 (3)

Support for eco-schemes shall take the form of an annual payment per eligible hectare and/or a per holding payment, and it shall be granted as incentive payments going beyond compensation of additional costs incurred and income foregone, which may consist of a lump sum. The level of payments shall vary according to the ambition level of each Eco-Schemes, based on non-discriminatory criteria. – Amendment of the European Parliament 20.10.2020

This design need not per se lead to a regression, but it is hardly different from greening. For example, it can be shown that about 800 €/ha is paid for the ecological priority area, which may be achieved as a cost in extreme cases for measures such as flower strips, but for many other measures and for many types of farm it hardly corresponds to the costs of the priority areas. In this respect, there have been income components in the past and there will continue to be, but now under the name “Eco-Schemes” which are voluntary, whereas in the past it was called “greening” and was obligatory for almost all farms throughout the EU, with exceptions for small producers and fodder growing farms.

There are small rays of hope, but these must be implemented by the Member States, namely the possibility of implementing collective measures or points systems. An EP amendment provides for the establishment of point systems.

Article 28 (1)

… To facilitate coherence and effective rewarding Member States shall establish point or rating systems. – Amendment of the European Parliament 20.10.2020.

Furthermore, farmers and “groups of farmers” were envisaged as beneficiaries of Eco-Schemes. Such rules do not yet result in environmental ambition and do not force an improvement, but at least Member States have the possibility to develop individually better solutions than those foreseen in this decision.

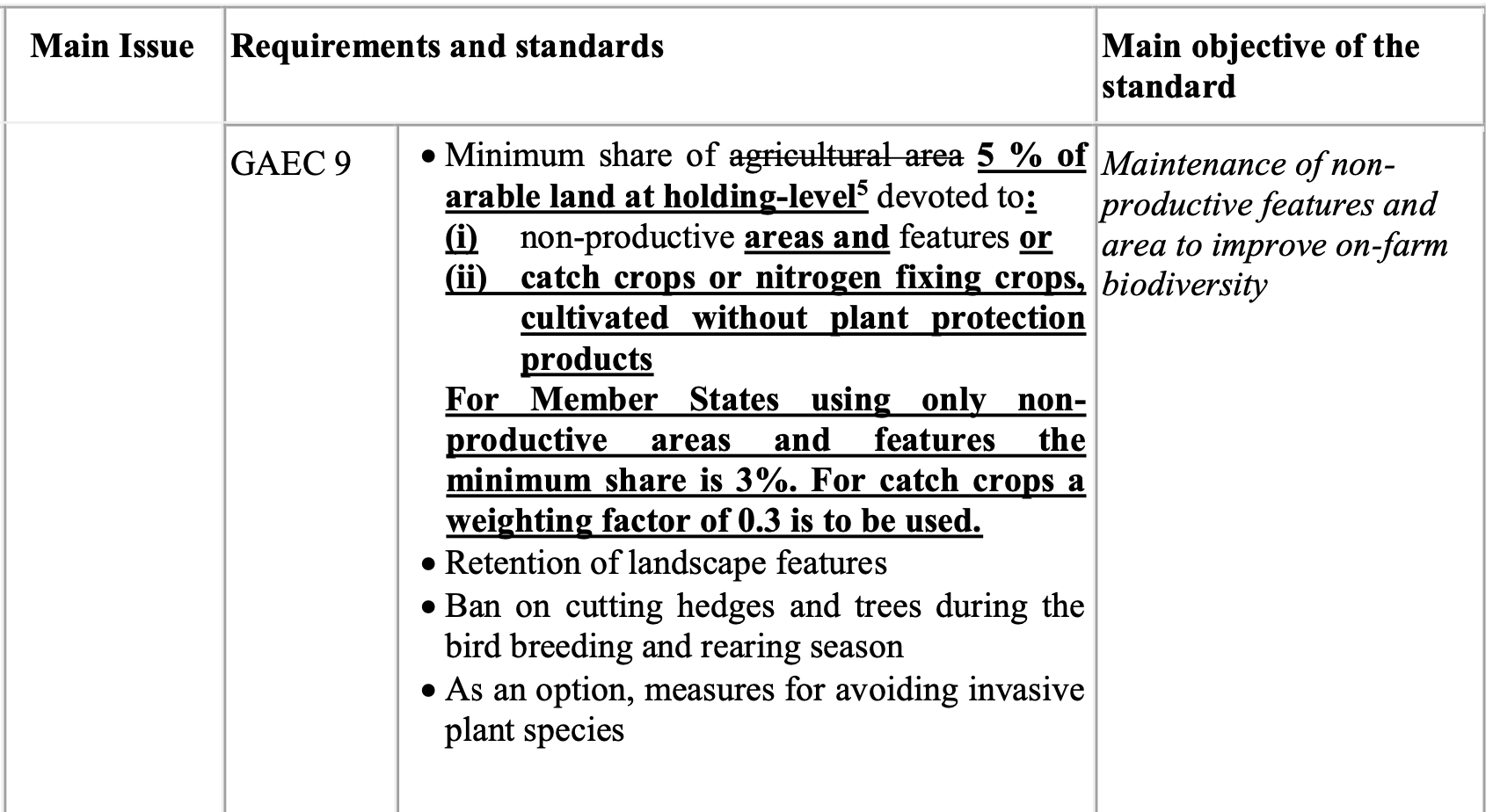

3. The definition of conditionality

Conditionality contains the basic requirements that each and every farmer must respect in order to receive direct payments. These basic requirements are called Good Agricultural and Ecological Conditions (GAEC). In the annex to the Commission’s draft, there were some basic requirements which would certainly have improved biodiversity and climate protection in particular.

3.1 Non-productive areas (GAEC 9):

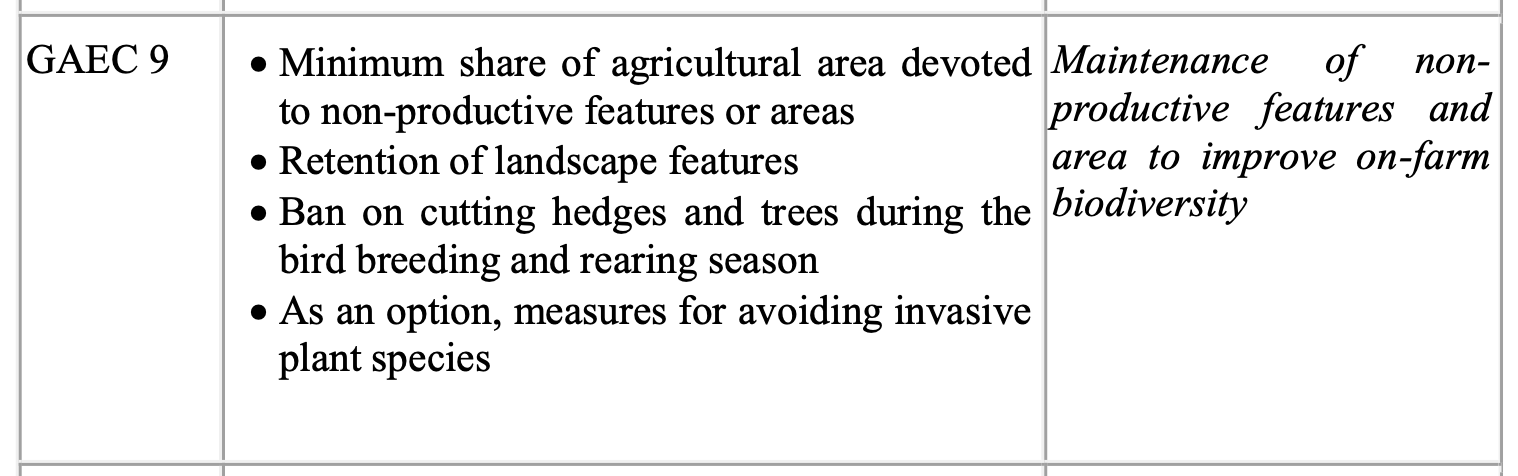

Here it was envisaged that x% of agricultural area was earmarked for non-productive elements (e.g. fallow land or flower strips) or landscape elements. According to the draft, the aim was to “preserve non-productive areas and areas to improve biodiversity”.

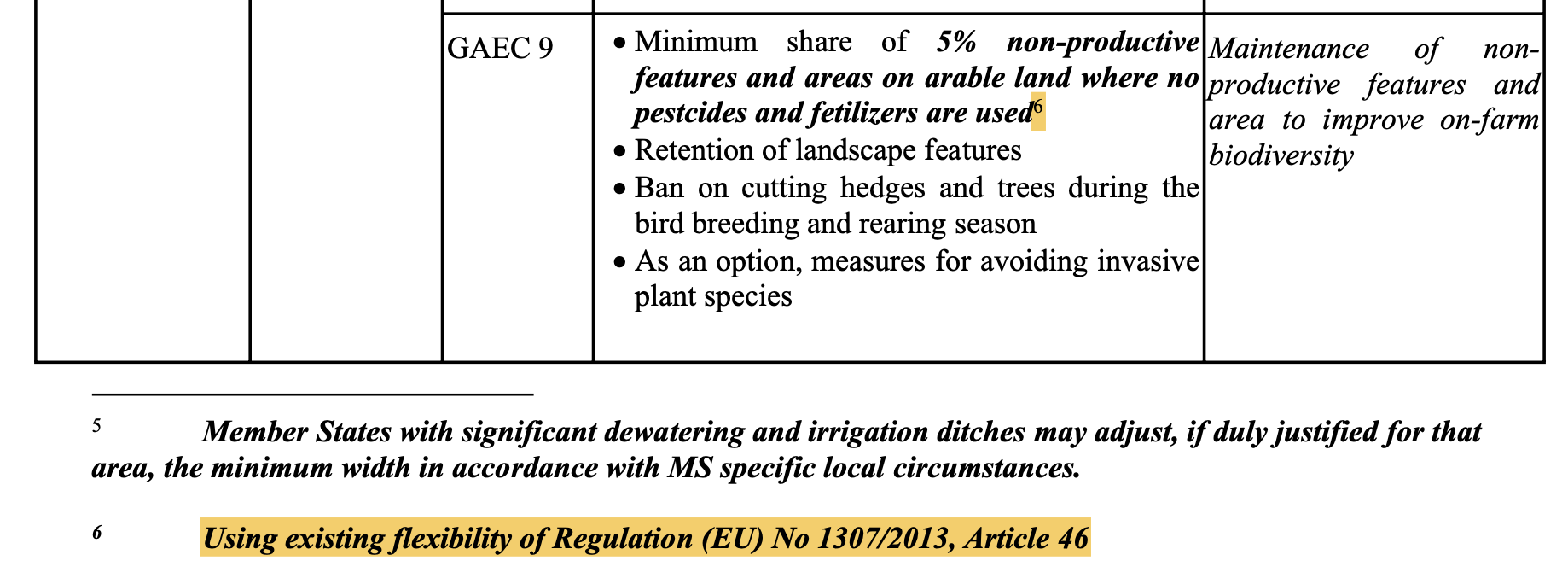

The Parliament and Council initially reduced the reference value to arable land, leaving 40% of the area (grassland, permanent crops, horticulture) out of the equation. Further options were also negotiated, such as catch crops and legumes. The amendment of the parliament looks like this:

Although the Parliament ostensibly stuck to the wording, it added a footnote stating that flexibilities from Article 46 of EU Regulation 1307/2013 – the article of the last reform that describes de facto greening – should be used. This means that x% of arable land is earmarked for the usual greening measures. The Parliament set a limit of 5% for non-productive land.

The Council was more transparent, naming the greening options directly, and even mentioning the ban on plant protection products for legumes, which applies to Ecological Focus Areas (EFAs) since 2018.

To evaluate these amendments, first it can be noted that the EU Commission’s 2020 Biodiversity Strategy proposes that 10% of non-productive land and landscape elements be set aside. This target definition is repeatedly cited by scientists from the environmental sciences and agroecology as a meaningful target, even if it must of course always be region-specific and differentiated in context.

It can also be pointed out that the net area (before application of the weighting factors) will already in 2018 account for more than 5% of arable land being farmed according to the EFA model – and that is the decisive benchmark after the changes in the Council and Parliament.

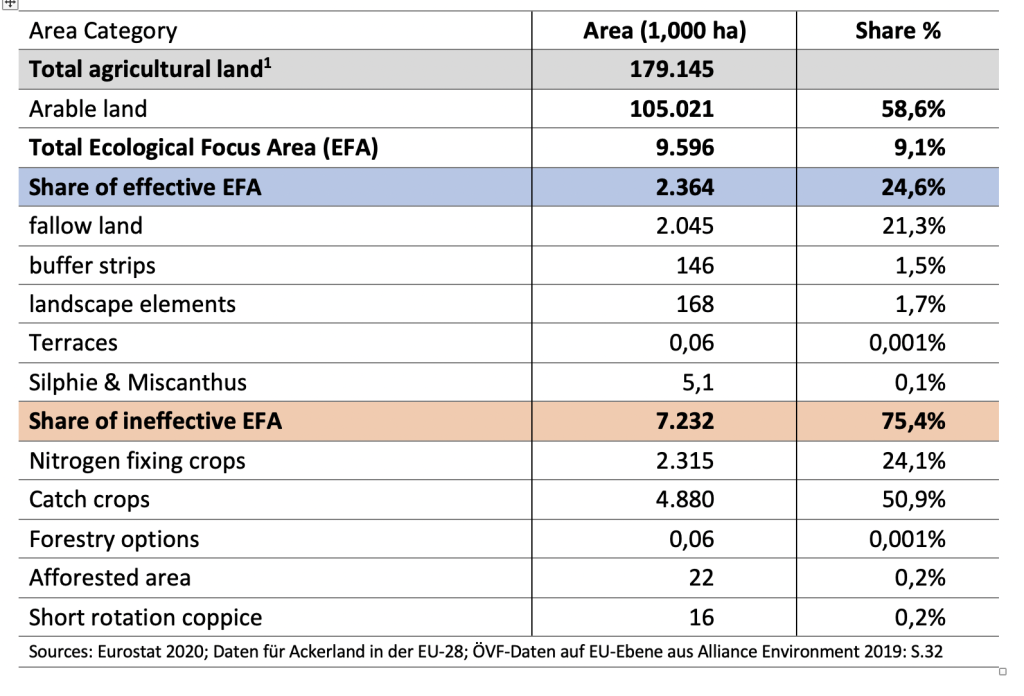

The following table shows which options will already be implemented in 2018 and net is 9% of arable land, mainly due to the ineffective catch crops and legumes options.

This begs the question: how can the 5% non-productive area be sold as a high ambition? It is still proposed to continue with EFAs in the same manner despite clear scientific criticism (see for example Pe’er et al. 2017 ; Ekroos et al. 2019 , Dellwisch et al. 2019). Intercrops and legumes have been negotiated into this option despite scientific criticism, and the target level is below what is already implemented in agricultural practice. This means that the draft reform also falls short of expectations in this respect.

3.2 Protection of wetlands and bogs

The protection of mire areas and mire rewetting are of central importance for the implementation of climate goals. The potentialities thereof are shown in the expert opinion of Germany’s Scientific Advisory Board for Agricultural and Food Policy from 2016. Important research on peatland protection is being conducted, with a recent paper by Tanneberger et al. 2020, published in September, illustrating the potential of peatland protection. The study also shows that peatland protection would be possible with the proposed CAP instruments.

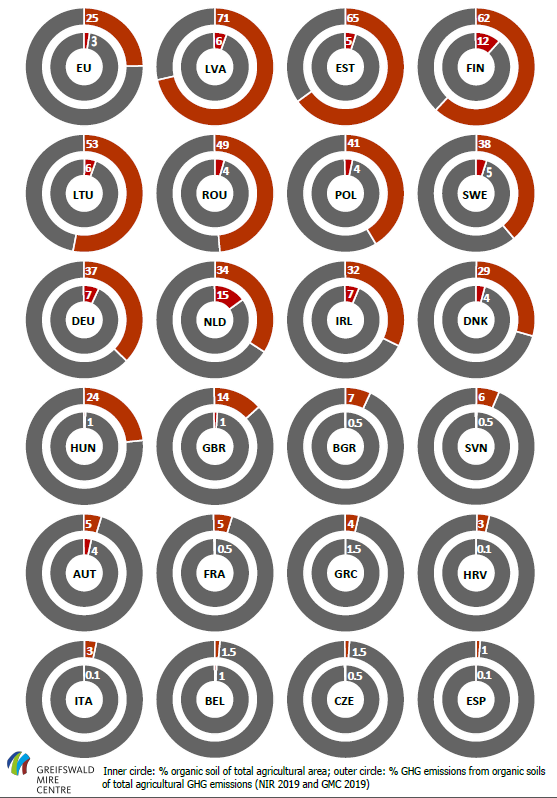

The share of organic soils in the EU member states and the level of moor protection already realised are shown by the following figure of the Greifswald Moor Centre:

Initially, GAEC 2 made the protection of wetlands and bogs mandatory:

GAEC 2: Appropriate protection of wetland and peatland (EC, 2018)

The aim was to protect carbon-rich soils and this obligation could have led to the protection and promotion of peatlands and wetlands.

The new provision following the Parliament’s decision is as follows:

GAEC 2: Effective protection of wetland and appropriate maintenance of peatland (EP-Amendment, 2020)

The difference is that this is now only about the appropriate conservation of peatlands and not about their protection. It is unclear what exactly ‘appropriate conservation’ should be. It is also a fact that most of Germany’s moors have been drained and are partly used as farmland and emit greenhouse gases in this use. In this respect, this provision does not provide benefit and it will not result in instructions for the protection of mire areas or organic soils. With these amendments, neither the Parliament nor the Council are developing a clear line on peatland protection and climate protection if only existing peatlands are to be preserved.

3.3 Ploughing of Natura 2000 grassland

GAEC 10: Ban on converting or ploughing permanent grassland in Natura 2000 sites (EC, 2018)

The objective of GAEC 10 is to protect habitats and species defined under the Natura 2000 Directive. Even before this requirement was introduced, the ban on ploughing in Natura 2000 grassland was weakened by the Council.

GAEC 10 Appropriate protection of permanent grassland in Natura 2000 sites according to the site-specific management plan (Council Amendment 2020)

The specific local implementation is now dependent on the specific management plan which might deviate from the general rule. Additionally, the term ‘appropriate’ is unclear.

3.4 Further basic requirements should not be used

A further and possibly far-reaching detailed amendment is laid down in Article 12.

Article 12: “In order to protect the commonality of the CAP and to ensure a level playing field, […] MS shall not prescribe standards additional to those laid down in that Annex against those main objectives, within the system of conditionality.” (EP Amendment 2020)

The conclusion of this amendment is not fully clear, but it reads to me that there should be no further basic requirements beyond the GAECs mentioned (and diluted). This may make sense at first in view of competition rules, as it establishes the uniformity of the rules (“level playing field”). But if the rules are hardly effective, it only means that member states themselves cannot formulate more demanding and effective rules. In this regard, the Parliament deviates from the principle of more responsibility and more flexibility for the member states: When it comes to environmental rules, there can be no upward deviations.

4. Flexibility vs. fixed rules

The European Commission’s basic design of the post-2020 CAP reform was geared towards more responsibility for member states. Member States were given more flexibility in implementation. Instruments were only roughly outlined and implementation was to be monitored by means of target indicators. In the new CAP, member states are primarily supposed to meet certain targets and are given much more freedom to do so. Although such an approach is worth considering in view of the very heterogeneous agricultural sectors in the EU, it has its pitfalls.

This flexibility is significantly increased by the amendments in both the Council and the Parliament. However, the current decisions deviate from the principle at one point:

There is a ring-fencing of 60% for direct payments, which clearly limits the overall room for manoeuvre.

In implementing the Strategic Plans, it is unclear how to measure objectives and levels of ambition in agricultural policy. One instrument was target indicators and another instrument was, for example, an instrument such as the GAEC baseline requirements. But the indicators are weak and it is also unclear how to measure a reference level. There is still room for development here, but the question of when implementation of, for example, an eco-scheme measure is still acceptable and when not remains a challenge if we do not want to end up with arbitrary and political assessments of strategic plans. In this respect, the life of the EU Commission is not getting any easier.

There has been some skepticism already after the publication of the reform proposal in June 2018. For example, in our Science study (Pe’er et al. 2019) we indicated that flexibility does not lead to more environmental standards. With the current decisions, exactly the scenario we feared in our analysis in 2018/19 has materialised: Flexibility is introduced without clear environmental rules, i.e. the Member States can do what they want and there is no benchmark to determine whether or not implementation will be acceptable in the Commission’s view. The European Commission has given up control, but it has not retained any security. It remains to be seen how this will affect the implementation of CAP reform.

5. Evaluation of the CAP-decisions: There is no common vision of agriculture in 2030

The majority in the EU Parliament and Council last week adopted decisions that reconfigure many familiar elements. At this point Julia Klöckner speaks of a change of system. However, the details show quite clearly that much is in fact recognisable. Already in the current funding period, direct payments were linked to environmental requirements via cross-compliance and via greening. Farms had to provide Ecological Focus Areas and the implementation of these priority areas was neither effective nor efficient. Politicians have not drawn any discernible conclusions from the numerous studies and have opted for “business as usual”. Moreover, many targets and requirements are formulated in such a way that in detail they even fall short of what has been achieved so far in 2014-2020. In this respect, no system change is apparent to me.

All in all, both the ministers and the parliamentarians lack a common vision for sustainable agriculture in 2030. They also lack the courage to tackle the necessary challenges via this contested support instrument. And so, the practice of direct payments, which benefit landowners but not always active farmers, will continue. There is no scientifically tenable justification for this instrument, yet the ministers are clinging to this lowest common denominator of EU agricultural policy, and there seem to be no other unifying ideas. It is also interesting that the decisions largely ignore the strategies presented by the EU Commission under Ursula von der Leyen (Farm-to-Fork and Biodiversity Strategy). Of course, these strategies are not perfect and need to be further refined and accompanied by impact assessments, but in principle (despite all the detailed criticism) these strategies would be suitable for eliminating some of the shortcomings and initiating a transformation. The majority of parliamentarians and ministers have not picked up the ball.

In the end, the question arises whether it makes sense overall to stick to a common agricultural policy. Clearly member states and the parliament are not managing to successfully renew this support instrument. In 2027 the EU budget will be under pressure because the EU has now taken on € 750 billion in debt. A non-reformable and dysfunctional agricultural policy could be put to the test in this scenario. For farmers, the changes could come very suddenly and without transition, because support instruments would be removed without replacement. Ignoring criticism of the CAP is therefore not helpful for farmers either. Furthermore, farmers are left alone with the challenges. Support instruments will continue to be deficient because there is no will to change. In this respect, the decisions are not good for farmers in the medium term, even if direct payments are maintained in the short term.

In the next few years, research will probably focus on how the Member States implement the flexibilities, and a focus will be on whether in some Member States the freedoms do lead to more ambition and examples of good practice. There has been no lack of indications from the scientific community. For example, the Scientific Advisory Council on Agricultural and Food Policy has issued several opinions (on the general orientation of the CAP, the effective design of environmental instruments and administrative simplification), there is the Leopoldina opinion “Biodiversity and Management in the Agricultural Landscape” from 2020, there was the paper “Action needed for the EU Common Agricultural Policy to address sustainability challenges” from spring 2020, which was supported by more than 3,600 scientists in the EU. In this respect, there was no lack of analyses, ideas and suggestions; The majority in the EU parliament and ministers in the Council did not want to take them. Members of the parliament have to decide freely, evaluate different interests and even discard proposals from civil society. However, the majority of EPP, S&D and Renew Europe will have to explain to the citizens, how a functioning agricultural policy can be designed without any scientific evidence. Many questions remain unanswered.

The process of reforming the agricultural policy towards more sustainable and environmental friendly farming systems will remain on the agenda, especially in Germany, where e.g. the EU leads an infringement case due to weak and insufficient implementation of the Habitat Directive, where the climate targets of the Paris agreement are currently not achieved and where citizens expect much more progress in the greening of agriculture. The financial consequence might be that additional funding will have to be provided from the federal government: A biodiversity fund to implement the Insect Protection Strategy appears necessary, as the CAP does not provide sufficient financial resources for this purpose and the federal states also need to shift more funds to CAP Pillar 2 (despite corresponding criticism). A climate fund for agriculture might be necessary to finance investments into rewetting of peatlands, realizing their huge potential to improve the GHG-balance of agriculture. Furthermore, other funds might be necessary to improve nutrient-balances at the farm level or to fund the transformation of the animal sector. In this case, the taxpayer pays for an ineffective and inefficient agricultural policy in Brussels, which hardly contributes at all to social goals, and he/she pays additional federal funds so that worse things can be prevented, at least in Germany. Also from this point of view, yesterday’s decisions do not seem unproblematic.

Still, some of the environmental challenges could be financed by the CAP, if the member states, here Germany, seek a more ambitious implementation. So the options are still there. However for Germany, it might be hard to imagine that the same Julia Klöckner, who was celebrating a low-profile negotiation result in Brussels, would seek the most ambitious implementation at home. This could be another Saulus-Paulus story, however, at this stage, that is rather hard to imagine. And at the end of the day, the incentives set by the CAP-decisions do not favour an ambitious implementation.

Sources:

Amendments in Parliament by Dr. Peter Jahr (CDU), Marial Noichl (SPD) and Martin Hlaváček, Jérémy Decerle (Renew Europe) to the Regulation and to the Annex of the Regulation.

Amendments by the German Presidency in the Council to the Regulation on Strategic Plans (11869/20) and the Annex (11869/20 ADD 1).

An earlier version of this article was originally published in German on Sebastian Lakner’s blog.

More on CAP Reform

Eco-Scheming | Council Adopts a CAP Position of no Ecological Substance

Parliament Plenary – Here’s the Amendments to Vote for and Against

Billions for CAP as an “extinction machine” – Farm to Fork Derailed

Parliament – Big Three Political Groups Try to Scupper CAP Eco-Schemes

Commission Proposes Four Flagship Eco-schemes – ARC2020 analysis