We’re back with Czech livestock farmer Josef, who says we need to trust farmers more. Farmers will make responsible decisions unless the system forces them to act irresponsibly. And he explains why the future of farming is in forgotten places.

We’re back with Czech livestock farmer Josef, who says we need to trust farmers more. Farmers will make responsible decisions unless the system forces them to act irresponsibly. And he explains why the future of farming is in forgotten places.

Making the land

In Czech the farmer is “zemědělec”, someone who makes (dělá) the land (země). But the farmers in the Czech Republic don’t make the land, they just harvest the land.

Making the land means that you grow trees, you make ponds, wetlands, you change little streams.

Today it’s much easier than 100 years ago because we have the machinery and we can make a pond in a few hours. You are living in the landscape and you see where the streams are after the rain, so you make a little pond.

But the agriculture office, the planning office, the water care office, the forest office will come and tell you: “No, no, no, you can’t do this, you must put it back.”

For example agroforestry is really popular. Last year was the first time I heard about it from the Czech Ministry of Agriculture. And wow, this is a technique which for 15 years has been implemented in lots of countries and it’s really cool.

But when you want to put some trees on your field it’s impossible. They take your subsidies from those areas.

No one can understand that you can grow wheat and trees in the same place.

Letter From The Farm | A Conscientious Objector to the Meat Industry

Dividing the risk

What I want to see is more freedom.

The structure of Czech agribusinesses today is not good: they do cows, they do crops. They specialize in a main income and a small second income.

This is not the future – trying to categorise everything you do in agriculture.

I think the success of agriculture in the future is a combination of meat and crops. All farms need resources to divide the risks in different weather conditions.

If you have fruit and nut trees and a few animals, maybe one year you will not have a lot of feed for winter so you cannot put the animals out but you have income from the fruit. Maybe the next year will be different.

So more freedom to say what agriculture is and what it is not.

Why doesn’t a golf course get subsidies?

If I put trees in my field it’s not agricultural land and I can’t get subsidies. But if a neighbour has a big house – this is a true story – with 10 ha of land, it’s a garden, a meadow, he can get subsidies for the meadow.

But it’s like, why doesn’t a golf course get subsidies? It’s the same thing.

The fence is all around with cameras, security everywhere, you cannot get in, but he can get money from subsidies because he’s mowing the meadow. It’s crazy.

This is agriculture: to make the land.

But if you put trees in the field, for the insects, to keep water in the land, it’s not supported.

If you put trees or something in your field, it’s up to you. It’s your problem if you have a lower income from the main crop.

I understand that there are some rules about erosion, about chemicals. These rules are pretty soft I think.

But the rules for changing the landscape, for new landscape features… you can do it but it’s not supported.

People who grow trees say the hardest decision is where to put the trees, because you must be aware that this is your choice for the rest of your life. In the countryside you will meet this tree every day. And you will lose some money from this part of the landscape because they will remove it from the subsidies map.

So it’s illogical.

We need more freedom to do what we think we should do.

Forgotten places

I see lot of opportunities in grazing animals.

In the subsidies policy, agricultural land is only fields and meadows.

In the past they used the whole landscape. They cut the trees for feeding, they grazed animals in bushes or scrub, on the side of the road, anywhere.

In the fifties – not because of the Communist era but because of tractors and machinery – the priorities changed. Number one was intensification of production in the fields.

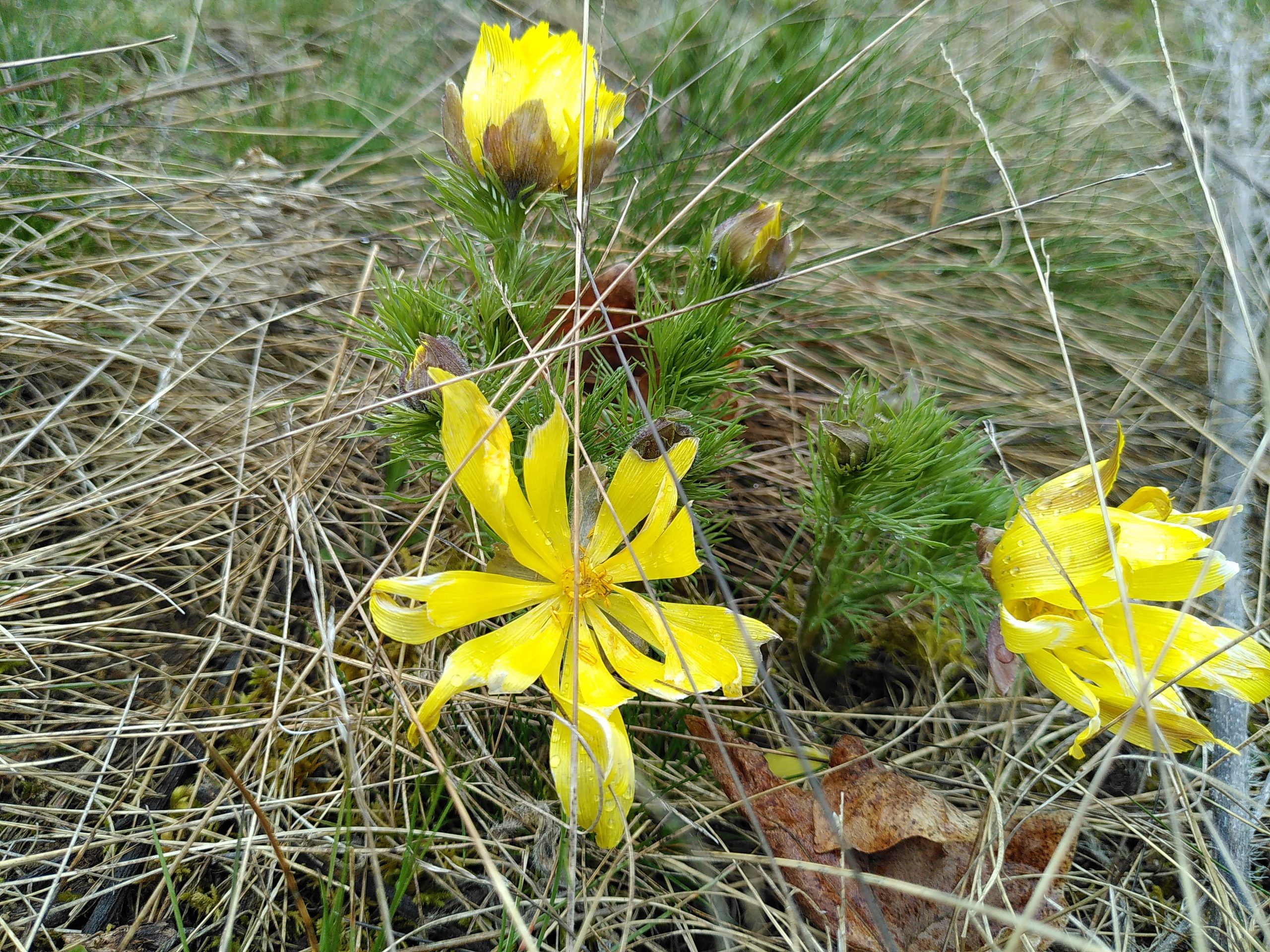

Totally forgetting that we have places that are not fields. Not fields, but not urbanised. Forgotten places. But historically, not so long ago, these places were used for agriculture too.

I see these places everywhere. There are a lot of opportunities in scrubland. This is a big opportunity to go there and to start grazing a little flock of sheep.

A lot of landowners don’t care about places like these. They care about their gardens and the fields they rent out, but not about these forgotten parcels that we can graze.

In the fifties, in the Communist organising structure, sheep were only used in a few places – in the mountains of Czechoslovakia, but not in ordinary agriculture in lowland places.

The focus of Communist agriculture was cows and heavy machinery on the fields and pigs for pork.

Because scrubland was not farmed intensively, it was not accessible for tractors or machinery.

It’s the same thing with mountain meadows or other places that become so special. But these places were forgotten.

And in the nineties, nature protection was really popular: the idea that you can’t do anything there anymore. And now they pay for expensive programmes to maintain these places.

Forgotten merits

I graze goats and sheep in a nature reserve. And I get money for grazing them. A lot of people say it’s not fair, he’s feeding them, he has the meat from the animals, so why should he get more money? But meat is so cheap that it’s not worth it.

I graze my animals for as long as possible, from March or April to December. So for 9 months of the year I don’t need the tractor to feed them. I just use it for baling for the winter and to bring them water.

These places that are so valuable because of the flowers, the insects, you can only maintain them with animals. You can’t mow it – it would be much more expensive. So you have to pay for that.

If we didn’t pay these agricultural subsidies, we would not have to pay as much for that. Because the price of the product would compensate it. But then the product would be expensive, it would not be for everyone, for low-income families and so on.

And in political terms the population doesn’t know about this. This is the biggest problem. They think, oh you’re the farmer, you have subsidies, you can buy this, you can buy that. But they don’t see that they can buy everything for half price.

Letter From The Farm | Half The Price Of Your Food Is Paid By The EU

Farming on borrowed land

The definition of “zemědělec” is expanding beyond the traditional meaning. Now anyone who looks after a plot of land can make the land: nature activists, gardeners, artists, hunters. It’s not just a privatized sector for landowners.

The golden rule of agriculture is the land is borrowed from our kids.

Farming can help to prepare for climate change, as well as feeding the population. But the merits of agriculture are often forgotten.

In order to speak freely about his activities, Josef (not his real name) has chosen to remain anonymous.

In conversation with Louise Kelleher.

More Letters From The Farm

Letter From The Farm | Rasputin The Ram & The Ethics Of Lamb For Easter Dinner

Letter From The Farm | Three Years In: Realism And Planning For Utopia

Letter From The Farm | A Conscientious Objector to the Meat Industry

Letter From The Farm | Half The Price Of Your Food Is Paid By The EU

Letter From The Farm | The Resilience and Privilege of a Rural Homestead

Letter from a Farm | Saving Carrottop – the Life of a Cow in Mayo

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.