The Czech Republic’s renewed appetite for protectionist food quotas is hard for the EU to swallow. But can quotas for domestic produce really yield results for food self-sufficiency? Comment from beef farmer Terezie Daňková.

The idea of food self-sufficiency for the Czech Republic passed into law in the Lower House of the Czech Parliament on January 20, 2021. Specifically, the Parliament passed an amendment that will require large food retailers to sell at least 55% Czech products and to increase this percentage every year. The amendment is part of a tobacco and food law that deals primarily with health and safety, inspections and dual quality.

Arguments for food self-sufficiency

Self-sufficiency, and especially food self-sufficiency, is my life’s work and an issue very dear to my heart. So three cheers from me? Not so fast. The coronavirus pandemic has clearly demonstrated the limits of individual states. Although an epidemic is a minor hardship compared to the potential horrors of natural disasters, war, the onset of dictatorial regimes, and so on, it has brought home to us that many basic necessities – take yeast for example – are not produced in our country. At least, not sufficiently. Not self-sufficiently.

But security of supply is just one argument for food self-sufficiency for the Czech Republic. Another is that the healthiest food is produced as locally as possible to the people who eat it. After all, even animals thrive when they eat food that comes from their valleys. It’s also best for the environment when food is produced in our backyard and not on the other side of the world where, for our food, the rich countries of the world are destroying rainforests, orangutans and indigenous people.

Another whole set of reasons for self-sufficiency are the economic arguments. Why buy food from anyone else, when I can pay Czech farmers who will spend the money here and pay taxes here?

To be clear, I’m not interested in discussing Czech self-sufficiency in oranges, or sugar cane – or even my beloved prawns. It’s wonderful sometimes to be able to have whatever you want from the other side of the world. And it’s great to come across Pilsner beer on the other side of the world, or Madeta milk (personally I’ve seen both on the other side of the world).

The devil’s in the technicalities

So that’s a very brief introduction into why I love self-sufficiency. I should sit back and celebrate this success. But it leaves a strange taste in my mouth.

I’ll start with the technical issues.

Who will monitor compliance, and how? The quota applies to retailers with a shop floor larger than 400 m2. These retailers file their receipts online [ed: a controversial Czech legal requirement known as EET] and essentially use an online stocktaking system. What happens when sales fail to meet the quota for Czech food items? An alarm beeps, the customers walk out of the shop and the retailer corrects the error? Maybe I’m being facetious, but after the experience with EET, I wouldn’t rule anything out. Will shops be inspected one by one? If the quota for French cheese has been filled, do I have to wait until other customers buy enough Czech cheese before I can buy the French cheese (incidentally I eat Czech cheese, and only very occasionally French cheese). The bill provides for an annual quota, so in the run-up to Christmas we’ll only be able to buy Czech goods?

Taboo in the EU

Another issue that was raised in the Lower House is the assumption that this law will never come into force. To be honest, I welcome the effort to open up taboo topics at EU level. Some countries have already attempted it, without success. Perhaps the day will come in the EU when the question of essential support for food regionalization is no longer damned. But I don’t know that it’s the best negotiating tactic.

And that brings me to the heart of the matter. This is my point of view on food self-sufficiency and the regionalization of food production: for the reasons I listed above, it is an absolutely crucial issue. But quotas are not the solution. They may be a help; hopefully they won’t be a hindrance – although they’re headed that way.

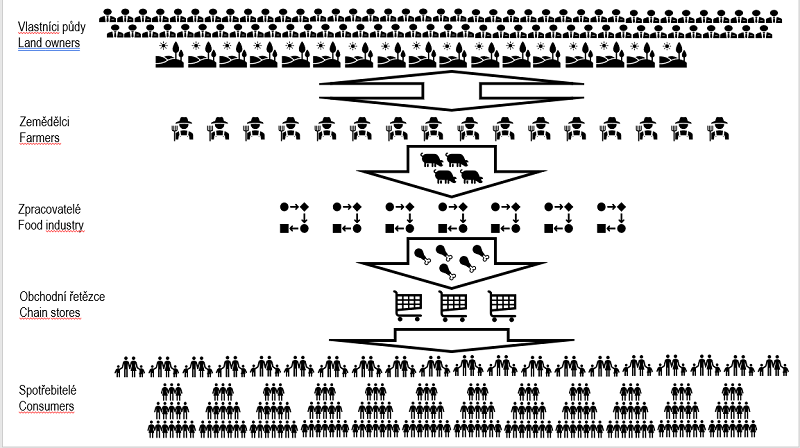

The only solution is a concentrated and targeted effort to revive cooperation and co-ownership in the farm-to-fork vertical. My grandmother would milk the cow and put the jug of milk on the table. Today, the cows are milked by a milking machine, the tanker takes it to the dairy and the milk travels tens of kilometres to the table. And that’s within a region. Imported milk may travel thousands of kilometres. In the Czech Republic the land is owned by millions of people. It is farmed by thousands of farmers. They sell their produce to a few dozen processors, who sell on the products to a handful of multinational retail chains that control the food sector in the Czech Republic. And millions of consumers shop at these chain stores.

If you feel that direct sales from farms are on the rise, you are right. I do direct sales myself – I’m a big fan. But we need to question the real impact of this rise in direct sales. Here’s a little test: think of a group of people around you, let’s say 10 people, with a mix of demographics. You, your partner, your children, their grandmother, an uncle in the village, your niece who lives in the city. Write down what your group ate in a fortnight. At work, at home, at school, in the retirement home, meals out. Add up the percentage of food that came from local suppliers. What do you get?

The demand for direct sales, for regional and local food, must be massive enough to drive a change. The Czech Republic is in a state of emergency. Let’s take advantage of this to set up regional supply chains for hospitals, kindergartens, schools, retirement homes. Let’s reconfigure the procurement models of state institutions and businesses, and reshape the buying patterns of households.

Keep in mind that farmers are not the only producers and distributors of food – and in this day and age they most definitely shouldn’t be. Direct sales have a place in supply. But to a greater extent so do the producers of raw ingredients who send them further along the supply chain. That’s how we get food in every shop and in every kitchen. If we want real self-sufficiency, for the long term, that won’t be subject to the moods and fluctuations of law-making, we must begin to grapple with the system of ownership in the supply chain. I know it’s a long and arduous journey. But it’s the only way to a stable outcome in the long run. Imagine if the whole supply chain, farm to fork, were controlled by people whose children’s schools are right next to the fields, processing facilities and supermarkets that grow, process and sell the food. The natural outcome would be good, Czech food. And they wouldn’t need alarms going off when shops come under quota.

If only food quotas could be more of a help than a hindrance to the concept of true food self-sufficiency. I’m off to have a mulled apple juice – Czech of course. I haven’t checked where the cinnamon and cloves are from. Here’s to good health!

This article was originally published in Czech in Argument magazine. Translated by Louise Kelleher.

More on the Czech Republic

Letter From The Farm | Half The Price Of Your Food Is Paid By The EU

Czech Republic | “No Forests, No Water, No Future” – Part I: Bugs in the Ecosystem

Czech Republic | “No Forests, No Water, No Future” – Part II: Moving On from Monocultures

Trouble With The Neighbours: Living Next Door to an Agri-Giant

Bad Czechs and Balances: Commission Audit Confirms Czech PM in Conflict of Interest