Despite the recent news that 90% of leading carbon offsets don’t have a tangible impact on capturing carbon, the EU Commission is moving ahead in developing a carbon farming certification scheme in the EU. ARC2020’s Mathieu Willard and Ashley Parsons present the context for his forthcoming report, to be published on the 7th of February.

Last week, the Guardian published an extensive investigation on the impact of carbon offsets. It wasn’t good news for the industry. The findings: more than 90% of Verra’s rainforest offset credits are junk, and do not represent real reductions in carbon. Yikes.

Does that mean the whole system of carbon offsets, voluntary or otherwise should hit the dumpster? Not quite. The EU Commission is making moves on certifying carbon removal schemes in the bloc.

The Commission’s got a plan…

Back in November, the Commission followed up on its Communication on Sustainable Carbon Cycles by proposing a Regulation on EU certification for carbon removals. One of the goals of the Regulation is to propose a certification system for carbon farming and create a new business model for farmers. So how does the Commission’s plan hold up to scrutiny? What are the risks and stakes of launching a large-scale carbon farming initiative in the EU?

Carbon farming is a new business model, and many private firms are already in the arena attempting to structure the market. As a Commission ambition, the subject has sparked intense debate.

On the one hand, the potential risks of scaling up carbon farming initiatives through private funding has brought backlash, with many NGOs highlighting risks for farmers, access to land and genuine climate change mitigation. On the other hand, the rapid growth of voluntary carbon markets, the increasing demand from the private sector for carbon credits, and the fact that carbon farming and voluntary markets are already being developed without concrete framing, shows that rejecting any carbon farming regulation – other than a prohibition – would be naïve.

But of central concern is the balance between the potential of carbon farming for climate change mitigation and the risk of large-scale offsetting politics to reach net zero goals being prioritised over real emissions reductions.

Will carbon farming be used as a cover-up for Business-as-usual?

How can offsetting function in a context of uncertain future climate change scenarios, natural events, change in practices, or errors in evaluating results?

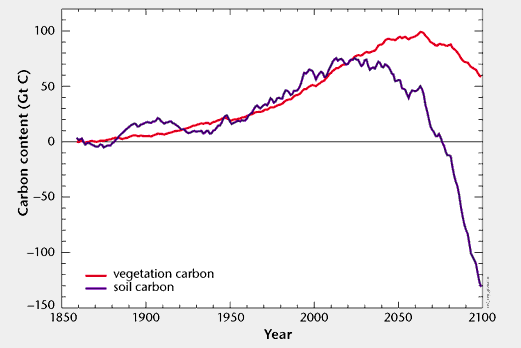

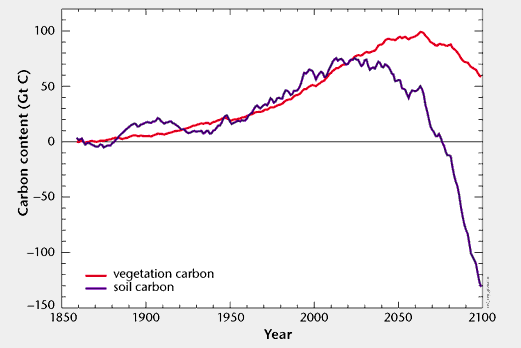

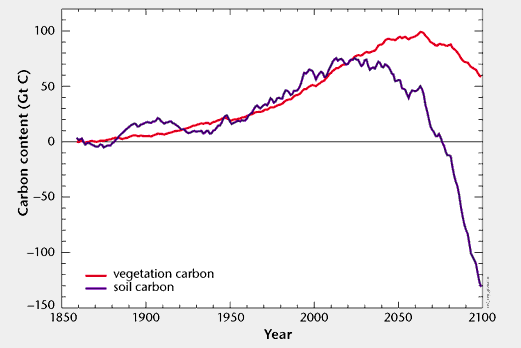

The figure above shows that, with global mean temperatures increasing, the carbon sink capacity of soils could start to drop in 2050, effectively re-emitting the carbon stocks built through carbon farming. In that case, carbon farming would have not only failed to mitigate climate change, but it would have temporarily covered-up the continuation of business-as-usual, effectively making it worse. This is only one example of how things could go wrong with carbon farming and definitely shows why offsetting should be the last resort tool.

But how can we ensure that offsetting is the last option – and not the first? How can we ensure that an offsetting scheme is only used as a last resort mechanism, used only after methods which avoid or reduce emissions in the first place?

Copycat – er, Copy-CAP

No one can argue with the fact that the agricultural sector has a role to play in climate change mitigation. It is also important to acknowledge that climate change mitigation should not be the only consideration, when thinking about how to re-orient agrarian systems. Other important social, environmental and economic considerations include climate change adaptation, enhancing biodiversity, reversing soil erosion, protecting water reserves, ensuring decent revenues for farmers, supporting the development of vibrant, resilient rural areas that are inclusive to woman, LGBTQ+ communities and migrant workers, and a well fed world – these and more are all urgently needed.

As of now, the main EU policy that could be used to reach this goal is the CAP. And public financing should remain the main tool for carrying out the transition, so as to ensure our agrarian systems can be shaped democratically, while protecting farmers. But until we can build a fairer and greener CAP, it would be foolish not to consider private financing that could boost the transition.

In the end, the central idea is that the Commission’s proposal for carbon farming should lay out a framework that can acknowledge and use the economic potential represented in Figure 1, while minimising the chances of the scenario represented in Figure 2 from happening. Moreover, risks other than climate change should be minimised, such as the risk of land grabbing.

ARC2020’s Analysis: Coming Soon

In that context, ARC2020 will soon launch a report commissioned by the Greens. The report aims at launching the reflection on what carbon farming could be, if we frame it well enough.

In the report, we present a few alternative ways to implement carbon farming that would provide ideas for such a regulation, with a specific interest for local and regional implementation as a way to minimise its adverse effects.

In the report, we present a few alternative ways to implement carbon farming that would provide ideas for such a regulation, with a specific interest for local and regional implementation as a way to minimise its adverse effects.

Moreover, we analyse the risks and stakes of carbon farming as a business model, we scrutinise the Commission’s proposal for a regulation in relation to those risks, and we check if a carbon farming program could be compatible with the CAP.

Ready to read it? The report will be launched on the 7th of February, during an event organised by MEPs Benoit Biteau, Bas Eickhout and Martin Häusling (9:30 – 13:00; Brussels or online). Our own president Hannes Lorenzen will be moderating the event.

Click here to register for the event

More

Food Security at the Crossroads: an Exhausted Model or a Sustainable One?

Despite the recent news that 90% of leading carbon offsets don’t have a tangible impact on capturing carbon, the EU Commission is moving ahead in developing a carbon farming certification scheme in the EU. ARC2020’s Mathieu Willard and Ashley Parsons present the context for his forthcoming report, to be published on the 7th of February.

Last week, the Guardian published an extensive investigation on the impact of carbon offsets. It wasn’t good news for the industry. The findings: more than 90% of Verra’s rainforest offset credits are junk, and do not represent real reductions in carbon. Yikes.

Does that mean the whole system of carbon offsets, voluntary or otherwise should hit the dumpster? Not quite. The EU Commission is making moves on certifying carbon removal schemes in the bloc.

The Commission’s got a plan…

Back in November, the Commission followed up on its Communication on Sustainable Carbon Cycles by proposing a Regulation on EU certification for carbon removals. One of the goals of the Regulation is to propose a certification system for carbon farming and create a new business model for farmers. So how does the Commission’s plan hold up to scrutiny? What are the risks and stakes of launching a large-scale carbon farming initiative in the EU?

Carbon farming is a new business model, and many private firms are already in the arena attempting to structure the market. As a Commission ambition, the subject has sparked intense debate.

On the one hand, the potential risks of scaling up carbon farming initiatives through private funding has brought backlash, with many NGOs highlighting risks for farmers, access to land and genuine climate change mitigation. On the other hand, the rapid growth of voluntary carbon markets, the increasing demand from the private sector for carbon credits, and the fact that carbon farming and voluntary markets are already being developed without concrete framing, shows that rejecting any carbon farming regulation – other than a prohibition – would be naïve.

Figure 1: A few examples of carbon farming projects being developed in the EU now. There are many more.

But of central concern is the balance between the potential of carbon farming for climate change mitigation and the risk of large-scale offsetting politics to reach net zero goals being prioritised over real emissions reductions.

Will carbon farming be used as a cover-up for Business-as-usual?

How can offsetting function in a context of uncertain future climate change scenarios, natural events, change in practices, or errors in evaluating results?

The figure above shows that, with global mean temperatures increasing, the carbon sink capacity of soils could start to drop in 2050, effectively re-emitting the carbon stocks built through carbon farming. In that case, carbon farming would have not only failed to mitigate climate change, but it would have temporarily covered-up the continuation of business-as-usual, effectively making it worse. This is only one example of how things could go wrong with carbon farming and definitely shows why offsetting should be the last resort tool.

But how can we ensure that offsetting is the last option – and not the first? How can we ensure that an offsetting scheme is only used as a last resort mechanism, used only after methods which avoid or reduce emissions in the first place?

Copycat – er, Copy-CAP

No one can argue with the fact that the agricultural sector has a role to play in climate change mitigation. It is also important to acknowledge that climate change mitigation should not be the only consideration, when thinking about how to re-orient agrarian systems. Other important social, environmental and economic considerations include climate change adaptation, enhancing biodiversity, reversing soil erosion, protecting water reserves, ensuring decent revenues for farmers, supporting the development of vibrant, resilient rural areas that are inclusive to woman, LGBTQ+ communities and migrant workers, and a well fed world – these and more are all urgently needed.

As of now, the main EU policy that could be used to reach this goal is the CAP. And public financing should remain the main tool for carrying out the transition, so as to ensure our agrarian systems can be shaped democratically, while protecting farmers. But until we can build a fairer and greener CAP, it would be foolish not to consider private financing that could boost the transition.

In the end, the central idea is that the Commission’s proposal for carbon farming should lay out a framework that can acknowledge and use the economic potential represented in Figure 1, while minimising the chances of the scenario represented in Figure 2 from happening. Moreover, risks other than climate change should be minimised, such as the risk of land grabbing.

ARC2020’s Analysis: Coming Soon

In that context, ARC2020 will soon launch a report commissioned by the Greens. The report aims at launching the reflection on what carbon farming could be, if we frame it well enough.

In the report, we present a few alternative ways to implement carbon farming that would provide ideas for such a regulation, with a specific interest for local and regional implementation as a way to minimise its adverse effects.

In the report, we present a few alternative ways to implement carbon farming that would provide ideas for such a regulation, with a specific interest for local and regional implementation as a way to minimise its adverse effects.

Moreover, we analyse the risks and stakes of carbon farming as a business model, we scrutinise the Commission’s proposal for a regulation in relation to those risks, and we check if a carbon farming program could be compatible with the CAP.

Ready to read it? The report will be launched on the 7th of February, during an event organised by MEPs Benoit Biteau, Bas Eickhout and Martin Häusling (9:30 – 13:00; Brussels or online). Our own president Hannes Lorenzen will be moderating the event.

Click here to register for the event

More

Food Security at the Crossroads: an Exhausted Model or a Sustainable One?

Despite the recent news that 90% of leading carbon offsets don’t have a tangible impact on capturing carbon, the EU Commission is moving ahead in developing a carbon farming certification scheme in the EU. ARC2020’s Mathieu Willard and Ashley Parsons present the context for his forthcoming report, to be published on the 7th of February.

Last week, the Guardian published an extensive investigation on the impact of carbon offsets. It wasn’t good news for the industry. The findings: more than 90% of Verra’s rainforest offset credits are junk, and do not represent real reductions in carbon. Yikes.

Does that mean the whole system of carbon offsets, voluntary or otherwise should hit the dumpster? Not quite. The EU Commission is making moves on certifying carbon removal schemes in the bloc.

The Commission’s got a plan…

Back in November, the Commission followed up on its Communication on Sustainable Carbon Cycles by proposing a Regulation on EU certification for carbon removals. One of the goals of the Regulation is to propose a certification system for carbon farming and create a new business model for farmers. So how does the Commission’s plan hold up to scrutiny? What are the risks and stakes of launching a large-scale carbon farming initiative in the EU?

Carbon farming is a new business model, and many private firms are already in the arena attempting to structure the market. As a Commission ambition, the subject has sparked intense debate.

On the one hand, the potential risks of scaling up carbon farming initiatives through private funding has brought backlash, with many NGOs highlighting risks for farmers, access to land and genuine climate change mitigation. On the other hand, the rapid growth of voluntary carbon markets, the increasing demand from the private sector for carbon credits, and the fact that carbon farming and voluntary markets are already being developed without concrete framing, shows that rejecting any carbon farming regulation – other than a prohibition – would be naïve.

But of central concern is the balance between the potential of carbon farming for climate change mitigation and the risk of large-scale offsetting politics to reach net zero goals being prioritised over real emissions reductions.

Will carbon farming be used as a cover-up for Business-as-usual?

How can offsetting function in a context of uncertain future climate change scenarios, natural events, change in practices, or errors in evaluating results?

The figure above shows that, with global mean temperatures increasing, the carbon sink capacity of soils could start to drop in 2050, effectively re-emitting the carbon stocks built through carbon farming. In that case, carbon farming would have not only failed to mitigate climate change, but it would have temporarily covered-up the continuation of business-as-usual, effectively making it worse. This is only one example of how things could go wrong with carbon farming and definitely shows why offsetting should be the last resort tool.

But how can we ensure that offsetting is the last option – and not the first? How can we ensure that an offsetting scheme is only used as a last resort mechanism, used only after methods which avoid or reduce emissions in the first place?

Copycat – er, Copy-CAP

No one can argue with the fact that the agricultural sector has a role to play in climate change mitigation. It is also important to acknowledge that climate change mitigation should not be the only consideration, when thinking about how to re-orient agrarian systems. Other important social, environmental and economic considerations include climate change adaptation, enhancing biodiversity, reversing soil erosion, protecting water reserves, ensuring decent revenues for farmers, supporting the development of vibrant, resilient rural areas that are inclusive to woman, LGBTQ+ communities and migrant workers, and a well fed world – these and more are all urgently needed.

As of now, the main EU policy that could be used to reach this goal is the CAP. And public financing should remain the main tool for carrying out the transition, so as to ensure our agrarian systems can be shaped democratically, while protecting farmers. But until we can build a fairer and greener CAP, it would be foolish not to consider private financing that could boost the transition.

In the end, the central idea is that the Commission’s proposal for carbon farming should lay out a framework that can acknowledge and use the economic potential represented in Figure 1, while minimising the chances of the scenario represented in Figure 2 from happening. Moreover, risks other than climate change should be minimised, such as the risk of land grabbing.

ARC2020’s Analysis: Coming Soon

In that context, ARC2020 will soon launch a report commissioned by the Greens. The report aims at launching the reflection on what carbon farming could be, if we frame it well enough.

In the report, we present a few alternative ways to implement carbon farming that would provide ideas for such a regulation, with a specific interest for local and regional implementation as a way to minimise its adverse effects.

In the report, we present a few alternative ways to implement carbon farming that would provide ideas for such a regulation, with a specific interest for local and regional implementation as a way to minimise its adverse effects.

Moreover, we analyse the risks and stakes of carbon farming as a business model, we scrutinise the Commission’s proposal for a regulation in relation to those risks, and we check if a carbon farming program could be compatible with the CAP.

Ready to read it? The report will be launched on the 7th of February, during an event organised by MEPs Benoit Biteau, Bas Eickhout and Martin Häusling (9:30 – 13:00; Brussels or online). Our own president Hannes Lorenzen will be moderating the event.

Click here to register for the event

More

Food Security at the Crossroads: an Exhausted Model or a Sustainable One?