A well designed redistributive payment is an essential tool to reduce inequalities among CAP beneficiaries and farming systems. But as is often the case, the best design strongly depends on national and regional specificities. The Czech Republic’s approach to the redistributive payment is a good example of that. The Czech CAP Stratgic Plan has now been approved by the European Commission. But in the weeks leading to the final approval, Agricultural Associations representing the larger farms of Czech Republic had been strongly protesting against the proposed 23% share of direct payments dedicated to redistributive income support. From the outside, one might think that these demonstrations were aimed at defending the exclusive interests of large farming corporations and landowners. But the reality is not so simple, as the situation could affect small and medium sized farmers as well. In this article, Terezie Daňková, a Czech farmer from South Bohemia, helps us understand the intricate history and structural composition of Czech farming that makes this issue so complex.

By Terezie Daňková, Mathieu Willard, Matteo Metta

Introduction

Through its now approved CAP Strategic Plan, Czech Republic implemented the highest redistributive income support budget of all Member States (23% of the direct payments envelop). This subsidy will be granted to all farms, on the first 150ha. Other countries have dedicated less budget share, but designed a more targeted approach via narrower eligibility criteria which can effectively shift money specifically towards the first hectares of small-medium farms. Some other countries have instead set up both low shares of redistributive payments (just the minimum 10%), and/or vague eligibility criteria that water down the very essence of this tool. Finally, other countries proposed a minimum redistributive payment as a way to remove capping over large landowners, thus backsliding in terms of fairness compared to the previous CAP (e.g. Italy)*.

In the last rounds of negotiations with Brussels (2022), the Czech decision about redistributive payments had been largely criticised by Agricultural Associations representing the large agricultural holdings. At first glance, it could be argued that this subsidy is necessary and justified by the need to support small scale farming and attract more young farmers. And it is true. But the specific Czech context invites us to appraise this measure with a sharp eye.

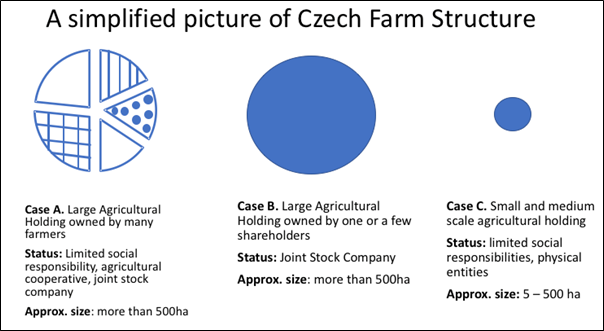

First, it is important to note that small/large scale farming does not bear the same meaning as it might in western Europe. In the Czech context, farms could be considered small even when ranging up to 200ha. This is due to historical events that shaped Czech agriculture. The concept of large scale farms is also to be defined with precision as two main structures can be found around Czech Republic. Some large agricultural holdings are owned by one or a few farmers. However others are owned by many farmers. All farms have their own specificities but the situation could be synthesised as presented in the figure below.

While trying to develop Figure 1, we contacted Martin Pýcha, Chairman of the Agricultural Union of Czech Republic, for additional information on the ownership structures of those different cases (e.g. approximative number of owners in each case). But as the public administration, including the State Agricultural Intervention Fund, treats each farm as a single entity, this kind of data was not collected.

In the current Czech Strategic Plan, all farms, regardless of their structure, will receive the same amount on their first 150ha. On that basis, farmers under case A can legitimately feel penalised. Indeed, you could find situations in which a farmer would receive only a fraction of the redistributive income although he/she works full time on the farm and his/her effective shares in the cooperative provide him/her with land ownership that is actually similar or smaller than a farmer on his own in case C. Table 1 below provides an example of this.

Here below, you will find an article written by Teresa Daňková, a Czech Farmer, detailing historical reasons for the current situation and reflecting on the counter-productive effect that poorly designed subsidiarity has on farming communities. Besides this insightful contribution, we will check out other CAP Strategic Plans and see if solutions can be found in other countries that might be applied in Czech Republic.

A fight between the small and the big helps no one

A redistributive payment of the amount that has been put forward reinforces the battle line of small versus big farms. None of today’s farmers is to blame for the structure of Czech agriculture, but also of Czech society in terms of the willingness and ability to actually live in a village and farm. Although the desire to achieve an ideal is understandable, we should be careful whether we are throwing the baby out with the bathwater. In our case, if we do not suport the layer of medium-sized Czech enterprises and their Czech managers, we will be left with a landscape managed by multinational holdings with islands of tiny Czech farmers.

First, some historical overview

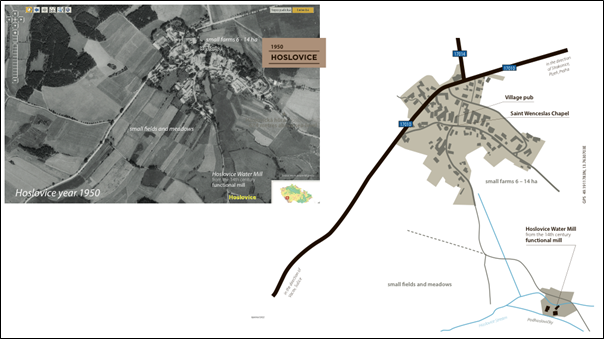

To understand the development, we have to go back a long way in history. The de facto liquidation of the Czech middle and small nobility after the Battle of White Mountain (1620) enabled the gradual consolidation of most land holdings in the hands of a few noble families. With the Czechoslovakia republic (1918-1939) came the land reform and, in a few years, the creation of a peasantry averaging a few hectares of fields and meadows, a piece of forest and a few cows. The future farmers bought the land mostly in several pieces, so that they could grow potatoes and grain on one piece, graze elsewhere, and water their cattle elsewhere.

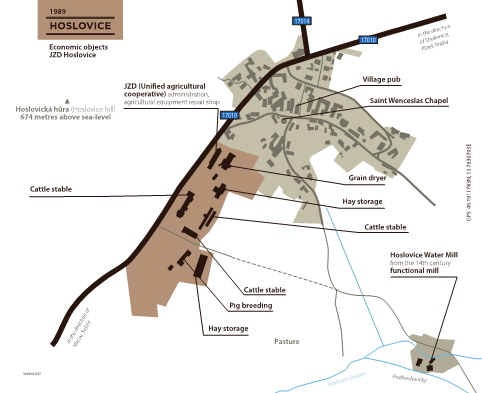

These peasants farmed during the First Republic (1918-1939), the Second World War (1939-1945) and were eventually, for the most part, subjected to forced collectivisation in the 1950s. At that time, the farmers on these farms were mostly second generation farmers, born on the farms or children when their parents started farming in the 1920s. By the 1950s they were in their forties and had to join cooperatives. Some of them lived until the Velvet Revolution of 1989, their children having grown up “under the cooperatives”. Many of those children chose a different path in life than working in agriculture.

In the 1990s, land and property returned to the original owners and their heirs. However, the structure of these assets had changed fundamentally. The tiny barns had long become large garages and behind the village often was one large estate. During this restitution period, properties were returned in the form of rural cottages and farmhouses adapted to the raising of a few cattle, plus a few acres of fields, as was the case before the communist era.

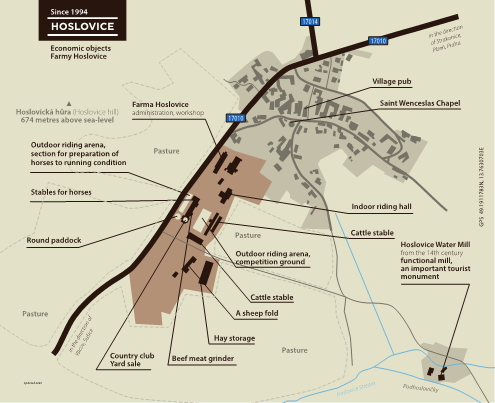

The vast majority of owners and their heirs did not want to farm the land. A minority took it up with what was restituted, sometimes succeeding in building small paradises over 30 years. Besides those small farms emerged the large group we are talking about in this article. These are the people who stayed to farm on the cooperative basis they knew at the time. Some remained cooperatives structurally or changed to form a company. They were able to come to an agreement, to exploit the potential of those agricultural areas. They bought the lands of those who did not want to go along with the peasant life and started farming in the era of free market capitalism.

In the last thirty years, many structures have already seen a generational change. In many places there have been and will continue to be mergers of companies because of the lack of heirs. And farmers’ children have all the rights to aspire for a life outside the countryside. The Josephine reforms established that right a long time ago (1780-90).

So here we have an agriculture that is simply largely made up of relatively large farms, up to two thousand hectares.

Small VS Big farms : an opposition that is not new in Czech Republic

For the past fifteen years, society and the media started to draw the equation confronting big farm-bad farm to small farm-good farm. The issues surrounding big fields notably in loss of biodiversity are certainly of great importance. But to resolve it by attacking the people who agreed to make a deal in the 1990s is not a happy outcome.

This battle between small and big farms started when the de facto abolition of support for ‘young farmers’ in legal entities was decided.

If you took thirty hectares and started farming on your own, you got a million Czech crown. And on top of that million, you got support points for every other investment application. But if you took over your parents’ share in a legal entity and took on the additional uneasy task of arranging consensus among the other owners (ask any flats owners commitee chairman), you would not qualify for support as a young farmer.

The reason for the abolition was because of the difficulty of control and the possibility of circumvention. For example, the owner of a farm could sign over a couple dozen hectares to any young person who would come once in a while for a weekend, and apply for a young farmer subsidy, without it being seen as circumvention. Certainly, it could be argued that, at the same time, the limit for investment grants was increased from 30 million to 150 million and that, therefore, compensation was provided to the larger ones. But since then, the line of war between the small and the large has been clear and deepening.

This injustice nurtured resentment in affected farming communities.

Redistributive payment

The increased budget for the redistributive payment is a mean to attract a number of small farmers into the countryside. Certainly a noble goal. But again, the reality of who will benefit from this subsidy is deepening divides It will be distributed regardless of farm structure, penalizing therefore the cooperatives or private structures owned by large groups of small farmers.

Let’s illustrate that with an example. In the new Czech CAP Strategic Plan, the allocated amount for the basic income support is 72€/ha, and the allocated amount for the redistributive payment is 154€/ha on the first 150ha. What happens if we compare the subsidies received by a cooperative structrure farmed by multiple owners and a smaller farm with one holder. The structures represented are hypothetical but proposed so that each farmer would own the same area.

| Small farm | Cooperative | |

| Number of holders | 1 | 20 |

| Number of hectares | 100ha | 2000ha |

| Hectares per farmer | 100ha/farmer | 100ha/farmer |

| Basic Income Support | 7 200€

7 200€/farmer |

144 000€

7 200€/farmer |

| Redistributive payment | 15 400€

15 400€/farmer |

23 100€

2 310€/farmer |

| Total | 22 600€/farmer | 9 510€/farmer |

Table 1: Comparing direct payments for 2 hypothetical farming structure in Czech Republic (source: Czech CAP Strategic Plan)

Althrough this scenario is hypothetical, it shows how discriminating the redistributive payment can be to farmers organized under cooperatives.

Again, penalising farmers that find themselves in structures that were historically formed to make the best out of a situation (the fall of the soviet union) is not going to unify the farming community around common goals for social and environmental justice.

We definitely need young people to farm dozens of hectares and create their own little paradise. But that life is not nearly as idyllic as it first appears. And in the meantime, it is absolutely certain that we badly need managers for the farming cooperatives and companies. And their task in terms of getting some consensus across multiple owners is a hugely difficult one, since cooperative members farm not only their own land, however take care of land the others as well. Any societal shift that discourages one of them, or leads their spouse, partner or offspring to say, “we don’t need this” is a terrible shame.

A redistributive payment that works for all ? The case of France’s GAECs

In France, farmers can decide to form cooperatives to farm some land together. Those legal entities are called GAEC (Groupement Agricole d’Exploitation en Commun / agricultural grouping for collective management), a French acronym not to be confused with the Good Agricultural and Environmental Conditions.

In order for each farmer that is part of a cooperative to be able to benefit from redistributive payments on his share of land, France has developed the “transparency for GAECs” mechanism, ensuring the recognition of activities provided by farmers that are part of a cooperative. Under certain conditions that ensure equity between individual farmers and farmers in cooperatives, each partner of the cooperative can thus apply for the same amounts of subsidies as individual farmers, for a similar share of land being farmed.

In the European legislation on CAP Strategic Plans, this opportunity for cooperative structures is clearly defined (for the redistributive income, see article 29-6): “In the case of a legal person, or a group of natural or legal persons, Member States may apply the maximum number of hectares referred to in paragraph 3 at the level of the members of those legal persons or groups where national law provides for the individual members to assume rights and obligations comparable to those of individual farmers who have the status of a head of holding, in particular as regards their economic, social and tax status, provided that they have contributed to strengthening the agricultural structures of the legal persons or groups concerned.”

Going back to Figure 1, this kind of tool could be used to evenly distribute the redistributive income among farmers from case A and case C. And by developing an effective cooperative transparency mechanism, it should be possible to avoid circumvention by case B.

We informed Martin Pýcha, Chairman of the Agricultural Union of Czech Republic, about this French mechanisms. This information was new to him but he seemed interested in his answer: “We will check it out and, if that is the case, we will start discussions on procedures that would also not penalise members of cooperatives and shareholders of other types of corporations in the Czech Republic for their willingness to cooperate with each other.”

Conclusion

Czech specifics need to be communicated in Brussels, and communicated well, regardless of the very emotional clash that is being fought here now. Solutions do exist as we’ve shown above, but are either voluntarely not used, or unknown to decision-makers and farmer’s representative bodies. Only with all cards put on the table and full transparency on how decisions are being made can we have a constructive debate and start working towards common goals.

When two argue, the third benefits. If we let the divide between individual small farmers and small farmers under cooperative or company structures deepen, it is the biggest landowners, who do not live in the region and just use it to generate profit at the cost of degrading the land and the region as a whole, that might end up benefiting. That would give yet another edge to the globalised food market and imported food, a hard blow for Czech food sovereignty.

This big vs small debate needs to be sorted out with a more detailed, targeted lense that do justice to the small-medium active farmers, individual or aggregated together in larger organisations. Only then can we start talking about other sensitive but essential topics in Czech Republic, such as countryside care, nutritional quality food, the number of landscape features that will be supported by public funding, soil fertility, farmer-landowner relationship, the advent of precision farming that brings with it the need for machinery with acquisition costs in the millions, and more. We need to solve this issue to be able to address all together the other challenges of our time.

Download this article as a PDF

This article is produced in cooperation with the

This article is produced in cooperation with the

Heinrich Böll Stiftung European Union.

More on CAP Strategic Plans

Can the CAP Strategic Plans Help in Reaching our Pesticide Reduction Goals?

Wallonia’s Observation Letter: A plan that fails to address climate and biodiversity crises

CAP Strategic Plans and Food Security: Fallow Lands, Feeds, and Transitioning the Livestock Industry

A Just and Green CAP and Trade Policy in and Beyond the EU – Part 2

A Just and Green CAP and Trade Policy in and Beyond the EU: Part 1

Bulgaria’s CAP Strategic Plan: Backsliding on Nature and Biodiversity

Changes “required” to Ireland’s CAP Strategic Plan – European Commission

French CAP Plan: What Opportunities for Change During the New 2022-27 Presidential Term?

CAP, Fairness and the Merits of a Unique Beneficiary Code – Matteo Metta on Ireland’s Draft Plan

ARC Launches New Report on CAP as Member States Submit Strategic Plans

Slashing Space for Nature? Ireland Backsliding on CAP basics

Quality Schemes – Who Benefits? Central America, Coffee and the EU

Civil Society Organisations Demand Open and Ambitious Approval of CAP Plans

CAP Strategic Plans: Germany Taking Steps in the Right Direction?

CAP Strategic Plans: Support to High-Nature-Value Farming in Bulgaria

Commission’s Recommendations to CAP Strategic Plans: Glitters or Gold?

German Environment Ministry Proposals For CAP Green Architecture

CAP Performance Monitoring and Evaluation Framework – EP Position

A Rural Proofed CAP post 2020? – Analysis of the European Parliament’s Position

CAP Beyond the EU: The Case of Honduran Banana Supply Chains

CAP | Parliament’s Political Groups Make Moves as Committee System Breaks Down

CAP & the Global South: National Strategic Plans – a Step Backwards?

CAP Strategic Plans on Climate, Environment – Ever Decreasing Circles

European Green Deal | Revving Up For CAP Reform, Or More Hot Air?

Climate and environmentally ambitious CAP Strategic Plans: Based on what exactly?

How Transparent and Inclusive is the Design Process of the National CAP Strategic Plans?

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.