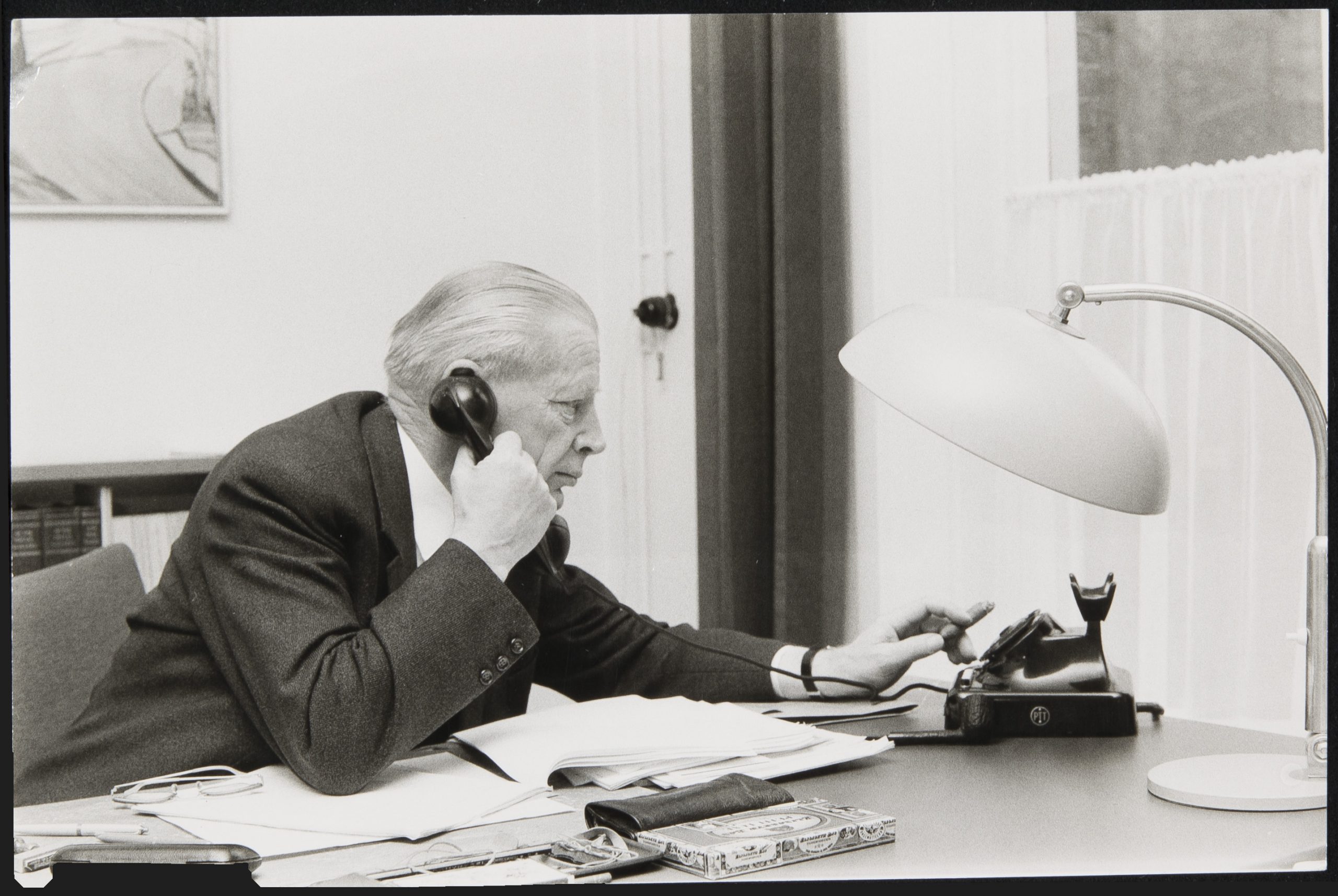

75 years have passed since Evert Willem Hofstee was appointed to the position of Professor at Wageningen University, which marks the beginning of rural sociology as a discipline and as a university department. What are the key features and how has it developed from 1946 to present? Prof. Dr. Han Wiskerke reflects on the 75th anniversary of what is now called the Rural Sociology Group.

By Prof. Dr. Han Wiskerke

Embedding rural sociology in the agricultural sciences

The beginnings of rural sociology at Wageningen University are to be understood against the background of its academic setting, that is, in the agricultural sciences. In 1946, Wageningen University was still an Agricultural College, and the technical and applied economic and natural sciences dominated the academic scene. In his inaugural lecture, Hofstee (1946) discussed the causes of inter-regional diversity in Dutch agriculture. The then prevailing agricultural sciences explained diversity in terms of differential physical-geographical conditions, differing distances vis-à-vis markets and differences in the general economic conditions of regions. Hofstee (ibid: 24) wrote thus:

“[T]he structure of agricultural life in a particular region cannot just be seen as a sum of attempts… to adapt oneself to the conditions one is facing. This structure can to a large extent, sometimes even decisively, be determined by consciously or unconsciously shared (within a specific social group) ideals, images and thoughts, which in their origin are detached from economic considerations”

In order to conceptualise this inter-regional agricultural diversity, Hofstee (ibid: 21) introduced the notion of farming style, as ‘a general accepted opinion, shared by a more or less coherent group of persons, about the way farming ought to be carried out’. With this concept and the thorough empirical analysis on which it was based, Hofstee clearly demonstrated the value of a social sciences approach for the agricultural sciences.

On traditional and modern-dynamic cultural patterns

The development of rural sociology between the early 1950s and the early 70s was framed by post-war Dutch agricultural policy and its strong focus on agricultural modernisation. Starting with a sociological interest in inter-regional agricultural diversity (i.e. different farming styles), Hofstee became increasingly interested in the agricultural modernisation process, particularly the question of why certain farmers were willing (or able) to modernise while others were not, appearing reluctant or unable to do so (Oosterveer & Spaargaren, 2001).

In order to understand and analyse the modernisation process in agriculture, rural sociologists at Wageningen developed the notion of cultural patterns and their conceptual dichotomy of traditional versus modern- dynamic (Hofstee, 1960; Benvenuti, 1962; Bergsma, 1963). Cultural patterns were understood as ‘the mental heritage of a specific social group, its norms, ambitions, ideals, opinions and images, etc.’ (Hofstee, 1960: 8). Following this dichotomy, also labelled as ‘differential sociology’, the past is the norm for judging the practices and strategies of oneself and others in the traditional cultural pattern, while in the modern-dynamic cultural pattern change is generally perceived, as positive (Oosterveer & Spaargaren, 2001).

According to Hofstee (1960), the level to which farmers internalised the modern-dynamic cultural pattern depended on a range of variables. What appeared to be decisive, however, was the degree of sociocultural isolation and level of interaction with the outside world (i.e. the more urbanised world). This could be measured and quantified, as demonstrated by the empirical studies of Benvenuti (1962) and Bergsma (1963). For example, the physical distance between a farmhouse and the nearest paved road operated as an indicator for the level of sociocultural isolation and was shown by Benvenuti (ibid.) to be positively correlated with the degree to which the farming practiced there was (still) traditional.

Towards the production of expert knowledge

In the course of the 1950s and 60s, rural sociology gradually shifted away from analysing the modernisation process through understanding its sociocultural dynamics at farm level towards producing expert knowledge that could be used in the policy-making process and facilitate the transition towards modern agriculture (Oosterveer & Spaargaren, 2001). The role of rural sociology in this modernisation process was to produce empirical findings that could guide the effective modernisation of Dutch farmers and thereby Dutch agriculture.

In this respect, a thorough understanding of the conditions constituting the different cultural patterns was considered indispensable, especially for actors such as extensionists, spatial planners and agricultural policymakers (Hofstee, 1960b). If Dutch agriculture was to move forward, than these actors had to remove the barriers (as identified by means of empirical sociological research on cultural patterns) that were preventing the transformation from traditionalism to modernity.

This vision of the role of rural sociology implied an intensification of the interaction between rural sociology, on the one hand, and agricultural modernisation and agricultural policy-making, on the other. Rural sociology thus became part and parcel of agricultural modernisation and succeeded in producing expert knowledge that was increasingly considered to be ‘as relevant as that produced by the technical agricultural sciences’ since ‘so well had rural sociology done its job that, in the early 1970s, Hofstee concluded that its task was virtually concluded’ (Anonymous, 1997: 2).

The fact that Dutch agriculture had, to a large extent, modernised, along with the establishment of new university departments, such as Extension Science and Spatial Planning, which had emerged from rural sociology, represented the summit of Hofstee´s contribution to rural sociology. In the remaining years of his professorship, Hofstee turned to historical sociology, and most of his staff dispersed to the newly established departments and other universities (ibid).

Rural sociology in crisis

This ‘golden age’ (Anonymous, 1997) of rural sociology was followed by a period of disarray and misery, characterised by confusion and conflicts about the focus of the discipline (De Haan & Nooij, 1985; Oosterveer & Spaargaren, 2001; Van der Ploeg, 1995a). Should rural sociology continue to study, build upon and contribute to the modernisation process or should new directions be pursued? This state of crisis was not just characteristic of rural sociology at Wageningen alone but of European rural sociology in general. According to Benvenuti, Galjart, & Newby (1975: 8-9), there were three main reasons for this:

-

- The close relationship between rural sociological research and governmental and agricultural agencies, resulting in a situation wherein the object of research was defined ‘for the rural sociologist by these agencies rather than by him for the theoretical progress of the discipline’;

- The strong emphasis on empiricism, leading to a situation in which fact-finding dominated, which implied that rural sociology had become a deductive empiricist discipline, producing a ‘multitude of facts, but little knowledge of what they mean’ (again, this was due to the close liaison with the above-mentioned agencies, as these preferred standardised data);

- The positivist stance of rural sociology, characterised by a strong reliance on the survey method, as a result of which the outputs of rural sociology were mainly ‘descriptions of rural social organisations and membership participation, the diffusion of innovations, and attitude data’, with hardly any interpretation of social interaction and social structure.

De Haan and Nooij (1985) added a fourth reason for rural sociology’s crisis in the 1970s: methodological individualism. Due to the close liaison with governmental and agricultural agencies, the emphasis on fact-finding and the dominance of the survey method, the cultural pattern theory became individualised: ‘without taking into account the social context, every farmer was assessed for the degree to which he participated in the modern-dynamic cultural pattern’ (ibid: 13).

The self-assessment of its state of disarray and misery eventually led to a reorientation of rural sociology. New issues appeared on the agenda, including the growth of agribusiness and its subsequent impact on farmers´ autonomy and dependence, social cohesion and the liveability of rural areas, the role of women on family farms and environmental concerns (De Haan & Nooij, 1985; Van der Ploeg, 1995a; Oosterveer & Spaargaren, 2001). These new issues all questioned, in one way or the other, the consequences of agricultural modernisation, focusing on the impact on family farms, farming families and rural areas.

From empiricist individualism to theoretical institutionalism

The developments in Dutch rural sociology in the late 1970s and early 80s can best be described as a shift from empiricist individualism to a more theoretically based institutional sociological approach (De Haan & Nooij, 1985). This shift in focus is most profoundly illustrated by Benvenuti’s (1975, 1982) TATE-theory. An acronym for the ‘technical and administrative task environment’, TATE refers to ‘all the institutions that increasingly structure and (de)legitimise the management of individual farms’ (Benvenuti, 1982: 112).

The institutions constituting the TATE are, among others, agricultural industries, banks, traders and extension services. According to TATE theory, the TATE expropriates parts of the farm, resulting in an important reallocation of decision-making power (from the farm to the TATE institutions). As such, it increasingly structures the development of individual farms (ibid: 117). In this process, the technologies developed by the TATE play a crucial role. Benvenuti (ibid: 122) developed the concept of technology-as-language to explain how farm development is being structured by the TATE:

[T]echnology is an ordering principle. Technology is an explicit language as it specifies the conditions under which it should be deployed. It is also explicit regarding the goals at which its use should be aimed.

In other words, the technologies (i.e. artifacts and services) developed by the TATE contain instructions (prescriptions, inscriptions) specifying how they should be used by farmers. The TATE theory was later criticised by rural sociologists (De Bruin, 1997; Wiskerke, 1997) for being too deterministic as it a priori assumes the structuration of farm development by TATE. Faced with this criticism, Benvenuti (1997) responded that in the late 1970s and early 80s, he perceived TATE as an ‘emerging reality despite its invisibility’. Thus,

Analytically speaking, to me, TATE was a conceptual tool for understanding and answering the question: how is the room for manoeuvre of individual farmers being restricted? The reason for posing this question – I realise now – was embedded in the somewhat simplistic assumption that this was the most relevant rural sociological question in those days.

In other words, the TATE-concept was first and foremost a research programme that gradually developed into a theory in which a certain degree of a priori determinism started to prevail. Nevertheless, Benvenuti’s TATE theory has been a major contribution to rural sociology, particularly due to its institutional approach (De Haan & Nooij, 1985).

The actor-oriented and labour approach

In the course of the 1980s, rural sociology shifted towards a more reflexive analysis of the agricultural modernisation process. This period was characterised by lively theoretical debates about actor, agency and structure (Oosterveer & Spaargaren, 2001). The Wageningen position in this debate was characterised by the development of the actor-oriented approach (see e.g. Long, 1997). According to this approach ‘farmers define and operationalise their objectives and farm management practices on the basis of different criteria, interests, experiences and perspectives’, meaning that ‘farmers develop, through time, specific projects and practices on how their farming is to be organised’ (Long & Van der Ploeg, 1994: 70). The actor-oriented approach also made a strong plea for a definitive ‘adieu to structure as explanans’ (ibid: 80), but without neglecting the effects of social, technical, economic and political factors on the practice of farming.

An important building block for the actor-oriented approach was the incorporation of the labour process approach in rural sociology (Van der Ploeg, 1995a). The labour process approach combined three elements considered to be indispensable for a thorough understanding of agriculture as a heterogeneous and highly diversified social practice (Van der Ploeg 1991):

-

- The production and reproduction process in agriculture;

- Farmers as knowledgeable and capable actors;

- The socio-technical relations that farmers practice, maintain and transform and which shape their daily lives and work.

The specificity of agriculture is, according to Van der Ploeg (1991, 1995a), situated in the unique nature of the agricultural labour process. First, this is an artisanal process, characterised by a close interaction between mental and manual labour (in contrast to the industrial labour process); and second, the agricultural labour process involves the transformation of living matter (animals, plants, ecosystems) into products. The intersection of artisanal production and the transformation of living matter explains the superiority of the family business as well as simple commodity production as the dominant organisational form (Van der Ploeg, 1995a: 253; see also Long et al., 1986).

The farming styles research programme

With the reflexive analysis of agricultural modernisation as overarching topic and the actor-oriented (more specifically, labour process) approach as its focus, in 1992, Jan Douwe van der Ploeg was appointed as Wageningen’s Professor of Rural Sociology and launched a new research programme.

Inspired by neo-classical economics, this model was based on the assumption that markets and technology determine the shape, contents, direction and pace of agricultural development. Furthermore, vis-à-vis markets and technology, according to the neo-classical approach, there is only ever one optimal position. Therefore, different positions in respect of markets and technology can be classified in terms of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ agricultural entrepreneurship (i.e. in terms of proximity to the optimal position) (Wiskerke, 1997). Against this, Van der Ploeg (1994: 9) argued that markets and technology afford – or rather constitute – room for manoeuvre, wherein different positions are taken, the results of strategic actions:

Farmers themselves, as social actors, are able to define and influence the way they relate their farming activity to markets and technology. Distantiation from and/or integration into markets and technology… is the object of strategic reasoning, embedded in local history, ecology and prevailing politico-economic relations.

These different positions were conceptualised as different farming styles. While Hofstee had developed this notion to explain inter-regional diversity in agriculture, Van der Ploeg re-introduced it to explain intra-regional agricultural diversity. Farming styles, according to Van der Ploeg (1994: 18), represent a specific unity of farming discourse and practice (i.e. a specific unity of mental and manual labour), entail a particular organisation of the labour process and represent a unique set of interlinkages between the farm and its techno-institutional environment. During the course of the 1990s, numerous farming styles studies were conducted in the Netherlands to explore and analyse diversity in dairy farming (e.g. Van der Ploeg & Roep, 1990; De Bruin, 1997), horticulture (Spaan & Van der Ploeg, 1992), intensive livestock husbandry (Commandeur, 2003) and arable farming (Wiskerke, 1997).

The farming styles research programme demonstrated that although Dutch agriculture had generally developed along the guiding principles of agricultural modernisation, this development had been far from uniform – or unilinear. On the contrary, Van der Ploeg (1995b) found that diversity in Dutch agriculture had increased significantly over the years; adopting a Chayanovian approach led to an analysis of farm economic accounts through a variety strategies was shown to be earning a good income. The farming styles research programme also demonstrated significant differences between farming styles regarding the environmental impacts of farming as well as strategies to reduce this and regarding the (im)possibilities of combining primary production with other functions (nature conservation, landscape management, green care, etc.).

The conclusions of the research programme had further implications for agri-environmental policy-making, with rural sociologists arguing that policies should focus on the goals to be realised and not prescribe the means to realise these goals (De Bruin, 1997; Wiskerke, 1997). Instead, farmers should have the freedom to choose those means most suitable to their own farming style. Finally, the programme had an important emancipating effect on the farming community. Farming styles that had been considered irrelevant, outmoded and outdated within the modernisation paradigm – such as ‘farming economically’ (i.e. keeping costs low by using own resources as much as possible) – were made visible and given scientific recognition for their merits.

From agrarian to rural development

The farming styles research programme in the Netherlands stimulated a European research programme aimed at describing and analysing the diversity, dynamics, impact and potentials of rural development practices using a multidisciplinary, comparative approach (Van der Ploeg & Long, 1994; Van der Ploeg & Van Dijk, 1995; Van der Ploeg, Long & Banks, 2003). This research programme was launched at a time of heated scientific and political debates about the future of Europe’s agriculture and rural areas. According to Marsden (2003), these debates centred around three different ideas about the future of agriculture and rural areas, namely, the agro-industrial, post-productivist and sustainable rural development models:

- The agro-industrial model assumed an accelerated modernisation, industrialisation and globalisation of standardised food production characterised by high levels of production, spatially extended food supply chains, decreasing value of primary production and economies of scale;

- The post-productivist model saw the countryside as a consumption space characterised by the marginalisation of agriculture (due to its low share in GDP), needs for the provision of private and public rural services and the protection of nature and landscape as a consumption good to be exploited by the urban population;

- The sustainable rural development model emphasised the spatial integration of agriculture, nature, landscape, tourism and private and public rural services, along with spatially and socially re-embedded, short food-supply chains, multifunctional agriculture, rural livelihoods, new institutional arrangements and economies of scope.

According to van der Ploeg, Long & Banks (2003), these three aspects are all transformed in and through rural development practices, implying that rural development is characterised by three mutually reinforcing development trajectories:

- Regrounding: new (compared to the modernisation approach) ways of mobilising resources, predominantly by building on the endogenous development potential of the local area;

- Broadening: the incorporation of other rural functions and activities (nature, landscape, water, tourism, etc.) into the farm enterprise, thereby transforming its relationship with and position in the rural area as well as broadening the economic base of the farm;

- Deepening: the transformation of the relationship between the farm and the food supply chain aimed at retaining more added value at farm level, for example, by producing high-value specialty products, on-farm processing and direct selling.

Taken together, these three trajectories were seen to be reshaping the farm into a multifunctional enterprise that delivering a much broader range of products and services than before. Impact analyses demonstrated that this broader range of products and services was also of economic importance. At the same time, the striking regional and national differences in rural development practices and trajectories within and among EU countries called for a better understanding of the social, economic, technical and institutional factors driving and hampering rural development practices more generally.

Broadening the horizon: food (and the city) on the research agenda

From the early 2000s, food emerged as a topic on the research agenda of the Rural Sociology Group. Like the work done on farming styles and rural development practices in the 1990s, food research came to the attention of rural sociology partly through the critique of modernised and industrialised food systems – referring to the ways and conditions in which food was grown, foodstuff manufactured, and these delivered to the market. This critique included negative appraisals of their environmental impact, their growing power inequalities and unequal distribution of added value (i.e. within the systems) and the lack of transparency in global food supply chains. The rural sociology food research agenda also began to focus on the emergence of a wide variety of alternatives to globalised and industrialised food-supply chains. These used short supply chains and alternative food networks (AFNs), characterized by notions of re-localization, social and spatial embedding and a turn to quality (Renting, Marsden & Banks, 2003; Watts, Illbery & Maye, 2005).

A steadily growing number and variety of research projects were directed towards the new concern. They included international collaborative research projects and scientific contributions to agri-food studies on short food-supply chains, local food systems and AFNs (e.g. Renting, Marsden & Banks, 2003; Wiskerke & Roep, 2007; Wiskerke, 2009; Roep & Wiskerke, 2012; Duncan et al., 2021). These scientific outputs mainly focused on the spatial and temporal dynamics, the socio-economic and socio-spatial impacts and the governance and diverse development trajectories of these short chains, local systems and alternative networks. The revisioning of food in terms of a systems critique along with the growth of unconventional, non-mainstream practices and organisations incorporated, among other things, a revalorisation of the traditional (as contemporary rather than unmodern).

Around 2010, the research agenda broadened further again with the study of food provisioning from an urban perspective – in other words, by linking the urban to the rural in food studies. The ongoing process of urbanisation – including new developments in urban food poverty – led to an important shift in the food security discourse: from a production failure issue to an accessibility and affordability challenge (Wiskerke, 2015). For many decades, food had generally been regarded in both research and policy-making as synonymous with agriculture and thus as a rural policy domain and hence an agricultural production challenge (Sonnino 2009). Food studies at the Rural Sociology Group was also, until then, rather biased towards the linkage of food supply (production and processing) to the rural domain. Approaching food sociologically as a whole system thus implied a reconsideration of rural sociology itself, which was now an orientation that also incorporated aspects of the urban.

Another emerging reality that pushed rural sociologists to embrace the urban domain was the growth in the number of cities and city-regions taking up the role of food system innovators and food policymakers (Wiskerke 2009). For these urban spaces, food became an entry point and lens through which several municipal challenges and responsibilities could be addressed and connected – such as climate change, waste collection and processing, social and spatial inequalities (in access to and affordability of food) and diet-related ill-health (Wiskerke, 2015). This area of food research particularly focused on a) the short-chain supply of food to urban and peri-urban areas (including urban and peri-urban agriculture); b) revaluing and (re) localizing public food procurement; and c) integrated urban and city-region food policies and strategies.

From rural to place-based development: moving beyond dichotomies

A final important change in our research approach has been another broadening of our horizon by shifting our focus from rural to place-based development from the early 2000s onwards. More generally, this relational approach has encouraged us to move beyond dichotomies, beyond not just rural and urban, which was already severely compromised, but also beyond local and global, production and consumption, and endogenous and exogenous.

A first step in this shift from rural to place-based development was the project entitled ‘Enlarging the Theoretical Understanding of Rural Development’ (ETUDE), which started with the notion of the rural web as a set of ‘interrelations, exchanges between different actors and activities, and positive mutual externalities’. Through a comparative analysis of rural webs in twelve localities across Europe, ETUDE proposed a classification of different territories, including specialised agricultural areas, new rural areas, and peripheral areas (Van der Ploeg & Marsden, 2008). Each type of territory was also shaped and characterised by different types of rural-urban relations; specialised agricultural areas were identified through spatially extended global food supply chains, new rural areas through multiple spatially proximate relations (green care, on-farm education, farm shops, etc.) and peripheral areas through spatially extended tourism relations. Concomitantly, our focus moved away from rural development as such towards regional or territorial development (Wiskerke, 2007) and hence beyond the endogenous-exogenous and local-global development dichotomies.

An important step forward in this process has been the SUSPLACE project, which focused on sustainable place-shaping. By assuming a relational approach, places are conceptualised as differentiated outcomes in time and space, shaped at the intersection of unbound ecological, political-economic and sociocultural ordering processes. Hence, places are mutually shaped and (continuously) reshaped and interconnected by these (trans)formation processes. Sustainable place-based development, as Horlings et al. (2020) note, then entails a well-balanced

- Sociocultural re-appreciation of respective places (beyond inherited assumptions)

- Ecological re-grounding of practices (in place-specific assets and resources)

- Politico-economic re-positioning (towards dominant markets, technologies and policies).

Most recently, in our EU research project ‘Rural-Urban Outlooks: Unlocking Synergies’ (ROBUST), undertaken between 2017 and 2021, we explored and analysed the diversity of interactions and dependencies between the rural and urban in a variety of domains (e.g. food provisioning, ecosystem services, social services, culture and heritage) and identified practices, governance arrangements and policies that foster mutually beneficial relations.

Six key characteristics of rural sociology at Wageningen

The continuities of rural sociology can be summarised as a list of six key characteristics or concerns, namely, people’s everyday realities, dynamics, meaningful diversity, comparative research, a relational approach and being critical and engaged:

- People’s everyday realities. Most of our research takes people in their everyday worlds as a starting point, and we work from there. People’s quotidian realities are primarily explored through specific practices – the ‘actions, processes, relationships and contexts through which and where the ordinary, real and everyday world is constituted’ (Jones & Murphy, 2010: 308) – with the aim of understanding what people do (or don’t do), how and why. Over the past thirty years, we have developed a focus on marginalised people and unconventional practices, giving a voice to the often unheard and making visible that which is commonly hidden, thus taking into consideration people and practices that are typically misunderstood and neglected in research studies and policy-making.

- Dynamics. In most of our research, we aim to link the present to the past, as the everyday practices and life-worlds of today (and their robustness or fragility) can only be understood by tracing their development over the course of time. This enables us, for example, to explore the emergence of path dependencies (e.g. (in)formal rules and regulations, vested interests, lock-in effects of long-term financial investments) and comprehend their impact on people’s everyday lives.

- Meaningful diversity. In our exploration of the everyday realities and spatio-temporal dynamics of people, practices and places, there a key concern has always been with diversity – not with diversity as such, but with understanding what certain practices or development patterns have in common and how and why they differ from other, more or less coherent sets of practices and development patterns. In other words, we have been interested in meaningful diversity. The work on farming styles, both in the early days as well as during the 1990s, is a clear example of this.

- Comparative research. Comparing practices and processes situated in different socio-spatial settings has been an important means to better understand both the contextual (e.g. place-specific) and more general (e.g. structural) factors influencing and shaping socio-spatial practices and development processes. Comparative research, therefore, has also been crucial to our understanding of diversity in a meaningful way.

- A relational approach. There are two ways in which relational thinking has been and continues to be important. First, starting with Hofstee’s differential sociology, relational thinking implies that a particular pattern (e.g. traditional) or set of practices (e.g. farming economically) derives meaning in relation to another pattern (e.g. modern-dynamic) or set of practices (e.g. farming intensively). Such relational thinking has been key to conceptualising meaningful diversity. Second, inspired by critical socio-spatial thinking, a relational approach has enabled us to move beyond treating dichotomies as distinct entities. We increasingly understand pairings like rural and urban not as binary oppositions but as sets of relations and connections. This has been of particular importance to our research over the last two decades.

- Being critical and engaged. A final key feature is that we critically analyse and reflect on the ‘conventional’ and ‘mainstream’ (e.g. agricultural modernisation) and thereby attempt to defamiliarize the familiar and question the taken-for-granted. we aim to be transformative by going beyond dominant understandings and constellations. This ‘engaged’ or ‘activist’ approach to research, for which we have been and still are sometimes criticised, has also been emancipatory by showing the potential of practices that often remain locked away, as it were, rendered uncredible and worthless.

In addition to these six key features, there are several other defining characteristics of our research approach, but these are more research-theme specific and thus discussed in the respective chapters on agriculture, food and place.

This is an edited extract from the book ‘On Meaningful Diversity: Past, present and future of Wageningen rural sociology’ which is available to download here.

More

The Influence of EU Policies in National Rural Digitalisation