In France, the land of “liberty, equality, fraternity,” territorial inequalities are still widespread. Exposure to pesticides remains one of the territorial inequalities that is hidden from the spotlight. This second part of our analysis continues the overview of pesticide impacts on the health of the French population discussed in part one. In part two, we consider the hidden human and financial impact of pesticides in rural areas. An analysis by Marie-Lise Breure-Montagne, of the Rural Resilience project.

Lire cet article en français

Impact of pesticides on rural communities

Not every French person is aware that their country remains the largest consumer of pesticides in Europe – just ahead of Germany. But, rural communities observe pesticide spraying practices with increasing suspicion, even indignation or worse, resignation.

Living together in rural areas also means accepting to debate the health impacts of agricultural actions. The four topics below provide a good indication of the content of the controversies, which, although they exist in France, are shared issues in Europe.

The health of populations in rural areas: can (and should) do better!

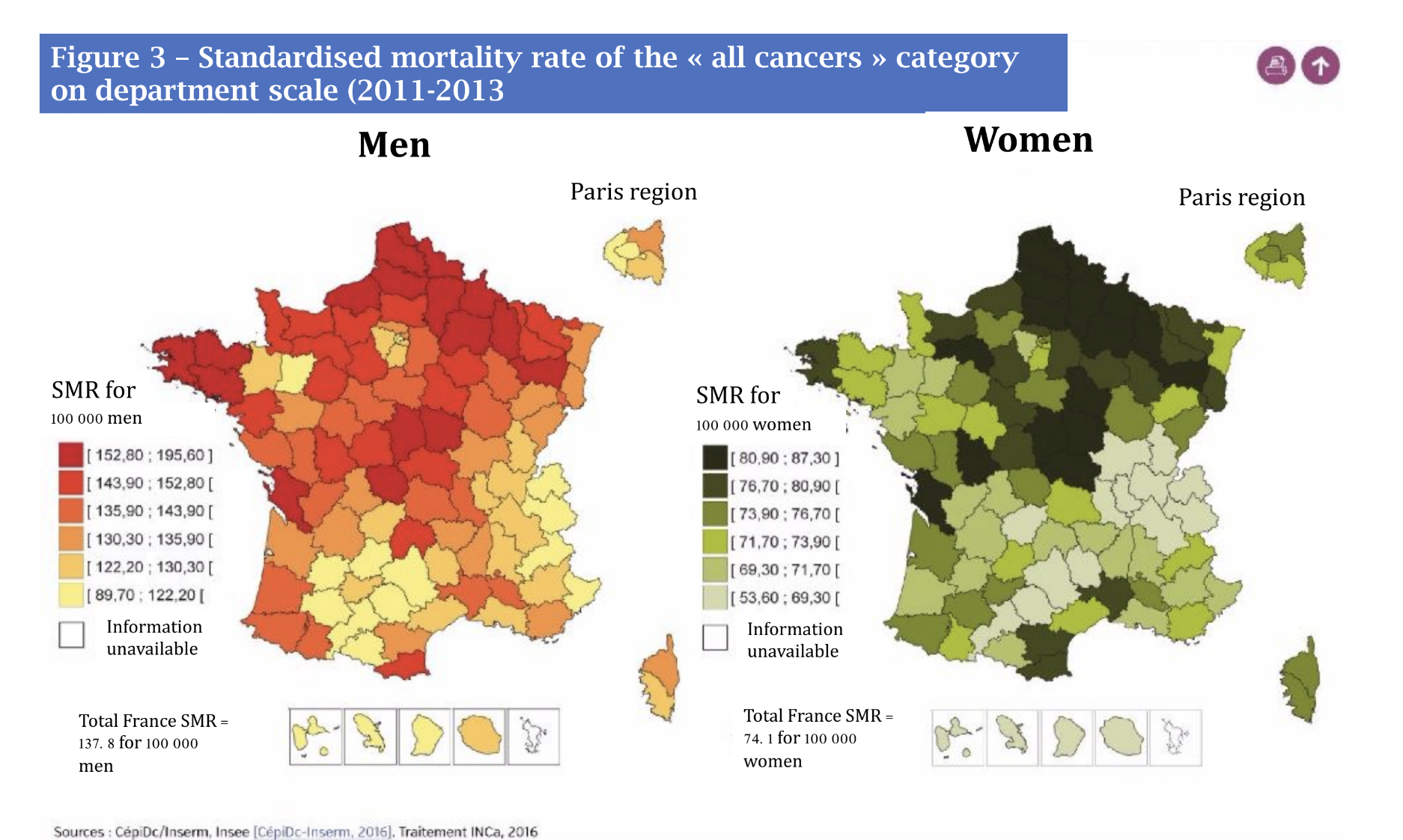

The map of cancer deaths (figure 3) can be overlaid quite well with areas where the population suffers from overexposure to pesticides. Specifically, this map for French women is more illustrative as they are less affected by other causes of cancer (tobacco/alcohol) than men.

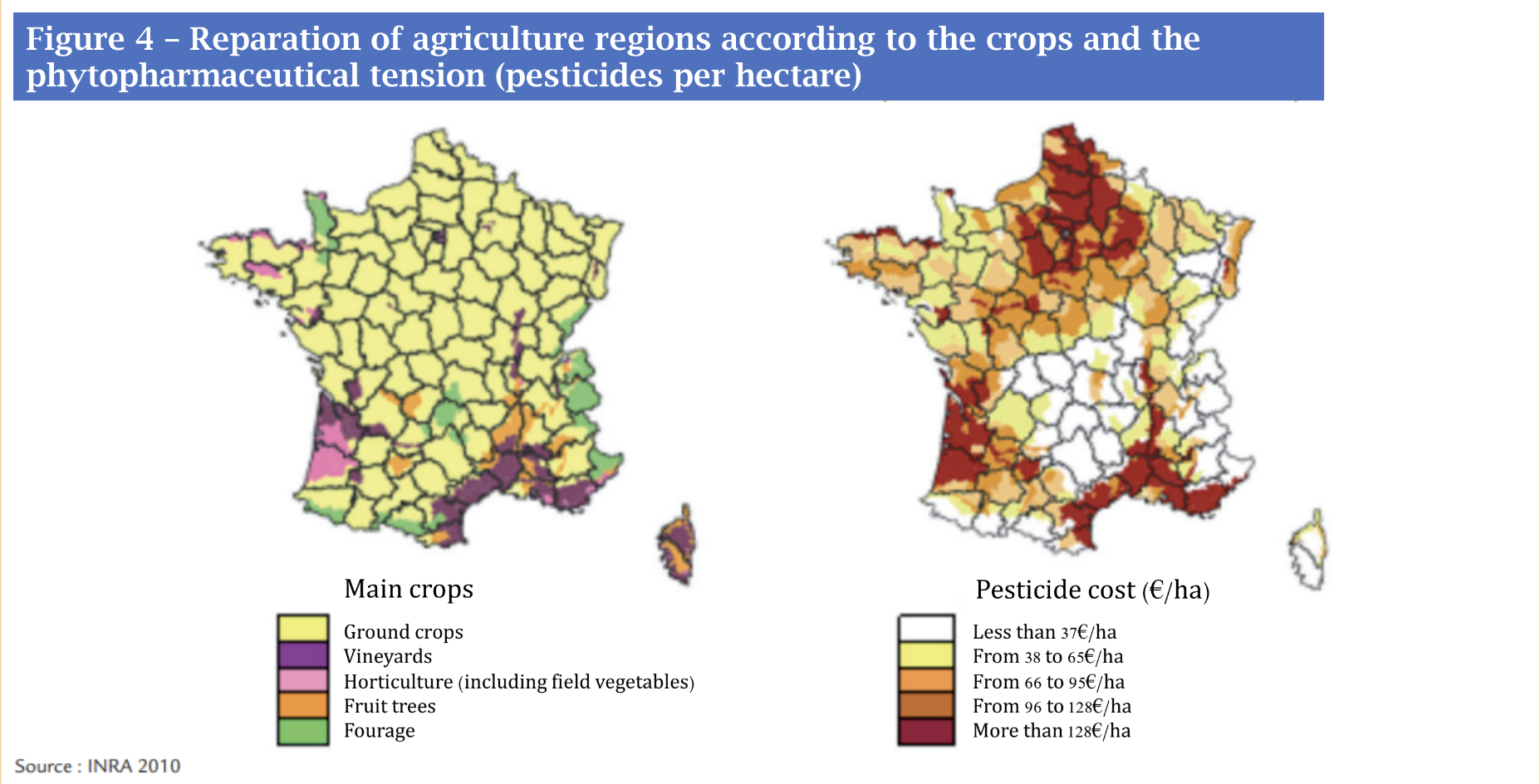

Nevertheless, correlation is not causality. What is certain: this geography of overexposure to pesticides, with sometimes lethal consequences, has been established for several decades, as illustrated in figure 4. And this is precisely what underpins the danger of this health situation.

The regions that are least affected by this “phytopharmaceutical pressure” are the (medium) mountainous areas (Pyrénées / Massif-Central / Alpes / Jura), where polyculture-livestock farming has been able to persist despite the transformative effect of the CAP.

It might be frustrating to see this correlation between cancer deaths and overexposure to pesticides but let’s go deeper. France has been regularly losing ground in terms of life expectancy. Long ranked 7th in Europe (in 1991, as in 2001), it began to slip to 9th place in 2011, to plummet to 19th place in 2021.

Are pesticides solely to blame? Of course not: the under-medicalization of French rural areas and their greater poverty (which can result in delayed diagnosis, a foregoing care, and therefore higher mortality rates for the same given pathology). Besides falling behind in Europe (from the 7th place in 1991 to the 19th in 2021), it has now been proven that life expectancy is lower in rural areas than in urban areas in France:

Life expectancy in rural areas continues to be up to two years shorter than in urban areas,” according to a new study by the Association of Rural Mayors of France.

It is also worth mentioning that access to affordable, timely medical care is increasingly difficult, (and pesticides induce chronic diseases, which are by definition long to treat, with heavy and recurrent follow-up care). And because the pesticide subject also concerns cancer, let’s also address the issue of under-equipped palliative care: the most rural areas are very poorly equipped. In short, rural residents with pesticide-linked illnesses have salt thrown in the wound by the healthcare policies.

The position taken by a community, along with rural mayor Gilles Noël, is easily understood:

We’ve woken up to the fact that it would not be a bad thing to avoid needing extra medical care by promoting health and well-being.”

In addition to “blatant social and territorial inequalities,” the diagnosis of the crisis in the healthcare system (particularly acute in rural areas) denounces, among other things, “the belief in the infinite progress of medicine and pharmacy as well as the limitless capacities of our social insurance payments,” and an “inadaptation to today’s dominant chronic and degenerative diseases” (Le Monde, 23/01/23). “Chronic and degenerative diseases,” including cancer and Parkinson’s disease, are linked to pesticide exposure, as demonstrated in Part 1 on farmers.

Like this elected official, many actors in rural areas do not dare to explicitly blame pesticides (a term nearly absent from this op-ed). And yet… a wave of anti-pesticide decrees has been issued by rural and peri-urban mayors (in 2019-2020, in the context of municipal elections), illustrating a growing awareness. Rightly so!

The ugliest face of pesticides: very sick children

“The hair of my 6-year-old son, in remission from cancer, contains agricultural pesticides” (lemonde.fr): The mobilization of neighbors overexposed to pesticides is embodied by this little boy and also by …

“a sensor used for measurements, located 30 meters from a school, in the town center of Montroy, more than 150 meters from the first crops. [The population is] therefore daily exposed to this cocktail of 41 products, some of which are neurotoxic and others classified as carcinogenic, mutagenic and reproductive toxic or endocrine disruptors. Children and pregnant women are particularly vulnerable.”

Isolated case? Certainly not. According to a study published by the IARC, in Europe, the incidence rate of childhood cancers has increased by 1 to 3% per year over the last three decades (mainly leukemias and brain tumors). Since the first epidemiological studies on the chronic effects of pesticides (launched in the United States by the National Cancer Institute in agricultural states such as Kansas and Nebraska in the 1980s), it is clear that “malignant blood diseases appeared overrepresented among the rural population of the Midwest.”

One of the advancements in the INSERM 2021 study is that it supports the presumption of a link between exposure to pesticides and malignant blood diseases in children (especially in the case of professional exposure to pesticides by the mother during pregnancy, or by the father in the pre-conception phase).

20% of children affected by leukemia will survive less than 5 years; 2/3 of survivors have or will have sequelae from their treatments, or even second cancers likely to occur throughout their lives.

There are 2000 cases of leukemia per year in French children (the portion attributable to pesticides is unknown, and not even studyable).

The damages caused by pesticides are much broader in children, as illustrated by the case of the devastated territories of the French Antilles. In the 2000s, the TIMOUN study (“child” in Creole) led by Inserm highlighted a link between levels of chlordecone exposure during pregnancy and an increased risk of premature birth.

In total, no less than 576 children make up the Timoun mother-child cohort to be examined over the long term by researchers: from analysis of umbilical cord blood to other stages of their development.

The deleterious impact of chlordecone is already massive on this overseas territory (incidence rate of prostate cancer in the West Indies nearly twice as high as the estimated incidence rate in metropolitan France over the same period); more than two decades after the end of its use, the effects are still present: this cohort study suggests that “cognitive abilities and externalizing behavior problems in school-age children are impaired by exposure to chlordecone during childhood, but not in utero.” An extreme situation showing that the massive use of pesticides causes a huge loss of opportunities at several levels for rural communities, and for a long time.

Definition of buffer zones, crystallization point of the SUR regulation… or a diversion subject?

During the debates on the SUR regulation, the issue of buffer zones between treated fields and residential areas was fiercely discussed.

To take a step back, studies on French and German territories have produced data to be highlighted. The French initiative is a database, PhytAtmo, grouping this data for the period 2002-2017 which was made public [in 2019 by Atmo-France]. The number of pesticides searched for each year in France varies between 150 and 250 depending on regional agri-systems. Between 40 and 90 active substances (herbicides, fungicides, insecticides) are detected annually in air samples, at variable concentrations in time and space.

“Certain low-volatile or prohibited compounds are also found. Both rural and urban areas are affected by air contamination by pesticides, suggesting a possible contribution from non-agricultural uses or even transport over long distances of molecules used in the fields” (INSERM, 2021, p. 123).

This indicates that there is still doubt about the relevant safety distances to be taken into account to regulate the spreading of plant protection products.

In the well-documented Pesticide Atlas (2023), there are findings that point to similar conclusions:

“In a study published in 2020, two German NGOs (Bündnis für eine enkeltaugliche Landwirtschaft and Umweltinstitut München) measured the contamination of air by pesticides and detected traces of 138 of them in 163 sites throughout Germany, including protected areas, cities, and organic farmland. […] 30% of the substances found were not authorized or no longer authorized in Germany.”

The distance between the residues found and their presumed application zone in Germany varied from 100 to 1000 meters – thus orders of magnitude 5 to 30 times higher than those already applied (in France: 10 or 20 meters) or discussed under the SUR regulation (30 meters).

Soils are also affected by contamination from pesticide residues and their metabolites, as an INRAE study brings attention to the persistence of pesticides in the environment (research project PHYTOSOL, launched in 2018 at the request of the French National Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health Safety, ANSES). Additionally, soil depleted by overuse, drought, and wind erosion (due to climate change!) is an inexhaustible source of contaminating dust for the air and water. Unfortunately, monitoring for this is lacking:

“Unlike what is done for aquatic environments and the atmosphere, there is no monitoring of soil contamination by pesticides on a territorial scale.”

The PHYTOSOL program has shown a “persistence [of pesticides in the soil] beyond theoretical degradability” (May 2023).

As these damning facts accumulate, so do maneuvers to lull the legitimate distrust of rural populations: “These measures are formalized by pesticide users in a departmental-scale charter of commitments, after consultation with persons, or their representatives, living in proximity to areas that could be treated.” All in vain: the Constitutional Council, which knows how to detect these political maneuvers has declared this contrary to the Constitution, and more particularly to Article 7 of the Charter of the Environment (2005) ; the issue was the method of elaborating these charters. One of the many wake-up calls to enforce the Aarhus Convention on these sensitive issues.

Previously hidden costs: soon to be a valid argument?

The most surprising thing when reading the SUR Proposal R1 – version for RSC meeting clean LW (004) – additional changes from table (003) (europa.eu) is to see:

“This proposal does not have an impact on the EU budget.”

But maybe it should?

On the subject of pesticides, the principle of “the polluter pays”, enshrined in the EU’s founding texts, is therefore not correctly applied: the compensation fund for farmers who are victims of occupational diseases is financed by the pesticide industry, without any comparison with the real harm or the actual number of victims.

And parts of pesticide cost are far from the EU budget: the budget for family caregivers of pesticide-affected patients is affected. What about the financial precariousness for a couple or a single parent, taking turns at the bedside of a leukemic child in a sterile room (for several months)? Only horizontal solidarity (e.g., donation of vacation days between employees, provided by labor law) can help them endure this caregiving marathon.

It is thanks to this long-running and massive denial of the health impacts of pesticides, with unforeseen socio-economic consequences, that the “pesticide system” has not yet collapsed in on itself. To put a telling figure on the global scale of this denial consider the international meta-analysis of 2016, published by D. BOURGUET and Thomas GUILLEMAUD (The hidden and external costs of pesticide use – Archive ouverte HAL). They highlighted that only 60 studies had been produced “worldwide” between 1980 and 2015 to evaluate the hidden costs and negative externalities of pesticides. In other words: almost nothing to include in the ex-ante or internal evaluation of this flagship policy of the agricultural sector.

In France, the Court of Auditors (“Cour des Comptes”), which represents the “interests of taxpayers,” provides various estimates on one of the four cost items [detailed by researchers, taken up by VIA CAMPESINA]: the environmental cost of deterioration of water (polluted with pesticides).

In 2011, in its study on the costs of the main agricultural water pollution, the CGDD estimated that the additional costs of drinking water treatment for local communities amounted to between 260 and 360 million euros per year for pesticides and between 120 and 360 million euros for nitrates.”

The Court praises preventive measures (for water quality), which could also be applied to human health: “Prevention… as an economically more advantageous system than the curative system.”

What is clear: cancer treatment costs are exploding. Already in the 1990s, for instance, the cost of treating prostate cancer (per patient) had tripled. Today, other therapeutic innovations are emerging, such as Antibody Drug Conjugates (ADC) : 4 on the market, 60 in development (for various types of cancers). Each year of survival costs at least 150k€ – 200k€ (per patient), to the “national solidarity”. As Rachel Carson prophesied, we are approaching a moment of truth where the situation will seem completely absurd, both in human and economic terms. The only certainty is that our public finances do not allow us to live another 30 years under this regime of absurdity.

Conclusion: Is the objective of a 50% reduction by 2030 achievable?

During the INRAE prospective work presentation symposium on March 21st, 2023, a Vice-President of FNSEA sarcastically explains that the European objective of reducing pesticide use by “50% by 2030” could encounter the same failure as the ECO-PHYTO plans. In France, ECO-PHYTO 1, which aimed to reduce pesticide use by 50% between 2010 and 2018, was a result of the 2007 Grenelle de l’Environnement. The ECO-PHYTO III plan will soon be launched in accordance with the Farm to Fork strategy. The source of this failure, according to him, was that “we have not listened enough to farmers”.

Whether the reduction is achieveable or not, this analysis highlights the idea that farmers have not been sufficiently informed (part 1). And more broadly, communities living near crops and rural communities are paying a high price due to the “pesticide” race (part 2).

It seems that the Court of Auditors, which controls public decision-makers, shares the same opinion:

“Santé Publique France could be asked to implement an information campaign on organic food and health as part of its mission of health prevention” (Court of Auditors, 2022).

However, this campaign might also target overexposed rural populations with public health prevention policies, and specific warnings.

Under the principle of equality between European citizens: the concept of equal phytosanitary pressure on the rural population should be taken into account in the implementation measures: with a more significant objective of giving up pesticides in certain regions/zones that are already heavily exposed.

Given the gaps in knowledge about the dangers of pesticides, and the absence of a comprehensive economic reasoning about their socio-economic impact, we can come up with actionable steps. In addition to the text of the SUR regulation, these steps rely on three main components: an information battle ; a legal battle, ranging from European institutions to Member States and local communities ; and support from independent scientific and technical studies.

Read More

Beyond the Harvest: Health Effects of Pesticides on French Farmers

Ernährungsrat: The democratic potential of Food Policy Councils in Germany

France | Democratising Food Policy – Tweaking The Financial Toolbox