Access to land is a pivotal issue for socio-ecological transition. The “Nos Campagnes en Résilience” project has heard this on the ground in France, where all of the rural actors we spoke to sounded the alarm.

To give space to the debate, we made access to land the topic of a panel discussion at our rural resilience gathering in north-west France last week (more on that to come). Unsurprisingly though, the issue permeated all of the discussions throughout the weekend.

To add to the conversation, we present our findings from research on the ground, over the past two years of the “Nos Campagnes en Résilience” project.

In the first of a series on hot topics around transition, we will look at land, water and soil. How are rural actors experiencing these issues? How are territories organised to adapt, and to move towards socio-ecological transition? How are the actors we spoke to – proactive members of their communities – tackling the urgent issues around access to land and natural resources? Analysis by “Nos Campagnes en Résilience” team.

Background

Rural actors all over France are pulling together to keep their villages alive and make the French countryside an attractive place to live and work. We knew we couldn’t meet them all, so we focused on farmers that were associates within farm cooperatives (GAEC, or Groupement Agricole d’Exploitation en Commun). The GAEC structure, specific to France, allows people to team up to share responsibilities and work on the farm. While the model has room for improvement, it allows farmers to organise themselves, to cooperate and to view work on the farm differently. All the GAECs we have met during these two years are invested in their territories, participate in local community life, and are involved in social and collective initiatives.

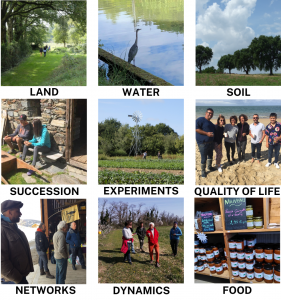

Our cross-cutting analysis highlighted nine themes that came up again and again in our interviews with farmers. Likely they will come as no surprise to you. We’ll be sharing them in this series of articles this autumn, to invite our readers to add their own inputs and perspectives.

The series is based on project updates shared with the participants during an online gathering on June 14, 2022. Rather than a scientific analysis, we seek to make the voices of all these actors heard, and share their thoughts and ideas with as many people as possible. We will be happy to provide additional information.

Let’s start with our feet on the ground. On the land. For the farmers we spoke to, the battle lines have been drawn. Access to land is a crucial issue. With it comes the question of access to water, and how to preserve the richness of our soils.

Land

“People will do anything to get hold of land” – Vincent Peynot, vegetable grower

Undoubtedly, access to land represents one of the major challenges for the coming years, as evidenced by the interventions and questioning of our partners such as Terre de Liens and the CIVAM network during the presidential elections in France earlier this year. All agricultural organisations, whatever their objectives, agree on this subject: access to land is difficult. Small farmers pay the price and the tensions are high.

“Access to land is important and we have to make people understand why it is important for the peasants, why it is politically key, and here the social question is important as is the relationship we have with the land.”

Mathieu Hamon, dairy farmer

Land has become a coveted and rare asset that generates anxiety, disillusionment and tension. However, the French state does not seem to grasp this dimension and is currently pursuing its public action in the same direction as in the past, without learning any lessons.

CAP – help or hindrance?

The CAP provides a policy framework for European farming, and financial support for the agricultural sector. But the farmers we met tended to be dissatisfied with the CAP, a source of inconsistencies that doesn’t correspond to their realities on the ground. As they see it, the CAP is a roadblock to freeing up land, and therefore to new entrants.

CAP payments are allocated for the agricultural area used, and these payments can represent for some farmers the equivalent to an entire income per month. One market gardener broke it down for us: “When we see an excavator arriving to pull up hedges, we immediately understand, it is to increase the agricultural area used and so receive additional payments. Others prefer to keep their land because they receive a CAP payment even though they are not cultivating it, but it’s much more advantageous than renting it to a small market gardener.” In this case, CAP payouts represent a hindrance rather than a help for farmers.

Infinite growth – a vicious circle

To obtain more CAP supports, farmers are always looking for new land. The purchase of new land allows them to increase their income or their capacity to invest. The increase in hectares forces the farmer to imagine a new way of working to produce on a large area: either hire workers or invest in more efficient equipment. This last solution represents significant investments with the purchase of high-tech and digital tools. The cost is so taxing that to repay their debts, the farmer buys new land. This spiral is generated by public policy, and a ministry of agriculture that leans towards mechanisms that encourage investment. This creates competition for agricultural land between farmers. Farmers are also seeing big investors come onto the scene.

Multinationals investing in land

The phenomenon is not new, but it seems to be intensifying and no longer confined to just a few producers. Farmers take a dim view of these new investors: whatever the objectives, the agri-food industry is upsetting the land ‘market’. Small farmers do not seem to be able to compete with these heavy hitters. Often framed as a boon for the territories, creating jobs and attracting new families. In the short term, it may seem like a glimmer of hope for village life – but what about the long term? Under the guise of controlling the entire food chain from production to market, will these corporations not tend towards a monopoly, and thus better control of prices and populations?

A SAFER bet for rural areas

Created in 1960, a network of regional development agencies known as SAFERs (Sociétés d’aménagement foncier et d’établissement rural) has been working to reconcile private interests and collective projects through the use of dialogue. SAFER plays an important role in rural areas for the acquisition of land. In consultation with agricultural authorities and local authorities, under the control of the French State, SAFER contributes to the sustainable development of rural areas. It manages a rural land market observatory, and can also buy land and even manage property. It allocates the assets acquired to candidates, private or public, whose projects are in line with public policies. Although there is room for improvement and action is sometimes limited, the SAFER should be welcomed in rural areas to maintain a balance between agriculture and other economic activities.

“It’s difficult for our young people to settle here, because it’s increasingly a tourist region that brings in more and more people who want to settle here and who can afford to buy farms and houses, and are driving up prices”

Eric Magnet, farmer and local councillor in the Drôme region

Tourism – who is reaping the benefits?

It’s not always easy for local authorities to arbitrate between tourism and agriculture. Certain regions of France are particularly confronted with this dilemma. During our tour of France, small-scale farmers in the uplands of Savoie, Drôme and Luberon alerted us to this complexity of sharing the land.

Land pressure is so intense in these areas that young people can no longer start farming. Tourism drives up the price of land; construction of hotels and leisure facilities eats away at the available farmland; farmers have to compete with high earners to buy land.

The two sectors being intimately linked, it’s a balancing act for local authorities to maintain viable and livable conditions for all inhabitants.

Water, a precious commodity

“It’s a problem every day because we rely on a small river called the Ambre. [In 2020], for the first time, we did her more harm than good. So we decided to stop pumping. We asked to be connected to the water network. Water is a critical issue.”

Fanny Serralongue, vegetable grower in the Drôme region

Water was a hot topic in the Drôme region, which was facing a serious drought when we conducted interviews in 2021. However, no region of France will be spared in the medium term. The drought that France experienced in summer 2022 , like the rest of Europe, put water back on the table for debate.

Agriculture is at the heart of the issue. While lack of water was occasional in the past, as climate change accelerates, it is the number one concern. How to feed the world when the land has no water?

Every farmer is trying to find solutions to this new challenge. Some are considering new crops that require less water. Others are building ponds to provide a small water reserve, and to promote biodiversity with the introduction of new species.

Farmers are innovative and imaginative in their solutions to share this ‘blue gold’. This is particularly the case for Sébastien Blache who, together with colleagues, has created a non-profit to look after water management.

“We are an association. We manage, with a water agency, a fixed volume of water, which is granted to us by the administration. We have 160,000 cubic metres of water to share, within the association. There are 25 of us, with 4 irrigating.”

Sébastien Blache, mixed farmer in the Drôme region

The question of water comes up on a daily basis. Water scarcity will profoundly change practices, as will soil preservation.

Photo © Christophe Milot

Preserving the richness of the soil

Modernisation, intensive crop growing and monocultures have depleted the soil over the past century. Agroecological farmers pay particular attention to preserving the soil and adapt their farming practices to this new challenge. Many have changed their practices, and are experimenting with new techniques to ensure production over the long term – for example, crop rotation.

“The comfort of collaborating with Cécile’s brother […] allows us to have rotations. It wouldn’t work otherwise. If we only had our 20 ha, we could only produce 3 ha of wheat.”

Ludovic Boulerie, grain farmer and baker

Crop rotation is essential to allow the soil to replenish. But farmers don’t always have room for rotation. Where they lack land, some farmers organise land swaps with neighbours. This informal exchange is based on a mutual agreement and requires significant planning. Land swaps allow farmers to respect the cycle of rotations without acquiring new hectares.

Conclusion

Land remains a crucial issue. Every farmer we spoke to is looking for solutions – either individually or collectively. We found that measures do exist, but are often underused, or diverted from their main purpose.

We cannot close this chapter without mentioning the association Terre de Liens, which works to enable access to land. Also worthy of mention is the municipality of Plessé in Loire-Atlantique, which is experimenting in opening up the debate around agricultural issues, by bringing elected officials and citizens to the table, with a view to establishing their own municipal agricultural and food policy (PAAC) and thus finding their own solution to the land issue.

“It hasn’t changed, but like you say: at European level there must be very laudable intentions, but afterwards, when you go down the ranks once you’ve applied it in the field, it’s completely forgotten and in fact the bodies, they exist, the tools are present but in operation, we cannot manage to use them wisely. It is always the same people who are in power and who have control over these tools.”

Hervé Mérand, dairy farmer

Land, a common good?

Land is precious to every farmer we spoke to. We heard these concerns in every interview. And many of them raised the question of land as a commons.

In great demand, land is highly valued by States and rural actors alike. One of the solutions brought up by the participants was to make land a common good. But what is a common good? Who manages it? How? Does becoming a common good solve the problem of land management and soil preservation? These are all questions to be resolved collectively, and are beyond the scope of this article. But the question remains open and all input is welcome. If you are also interested in this question, or if you wish to share your experience, do not hesitate to reach out.

Coming soon in the second part of this series: the issue of succession and knowledge transfer. Why? Because the farmers we met are keen to pass on what they have built: the farm, but also the know-how, the expertise that has allowed their farm to succeed.

Nos Campagnes En Résilience is ARC2020’s project to help build rural resilience in France. Visit the project page here and follow us on Instagram, LinkedIn and Facebook. If you’d like to get involved, contact our project coordinator Valérie Geslin.

More on rural resilience

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.