€100 billion of CAP funds attributed to climate action had “little impact” on greenhouse gas emissions. That’s according the European Court of Auditors, in a report released 21st June. Here we unpack in detail where and how CAP is failing on climate, and what the auditors recommend. Part one of two – part two will critically assess the report, with a particular focus on organic farming. By Oliver Moore.

Overview

E100 billion spent and little to show for it. That’s the stark situation the European Court of Auditors laid out, when assessing the value for money Europe’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) for climate action. Climate spending represents 26% of the overall CAP budget, which in itself is half of EU’s total climate spending – yet overall farm emissions are not decreasing.

Comparing the 2007-2013 and 2014-2020 periods, the auditors found that “most mitigation measures supported by the CAP have a low potential to mitigate climate change. The CAP “rarely finances measures with high climate mitigation potential.” Unsurprisingly, agriculture emissions “have not changed significantly since 2010” the report states.

Read the Special Report CAP and Climate (English)

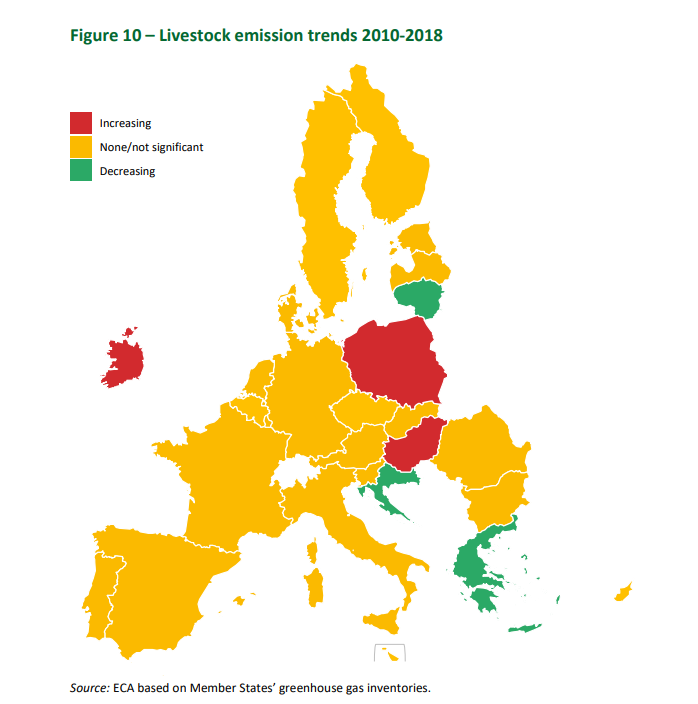

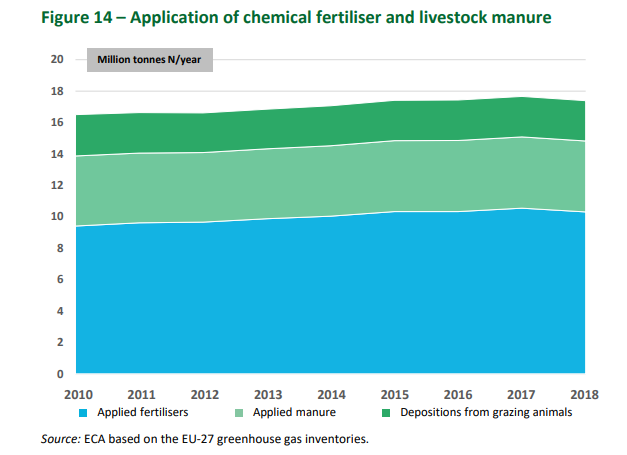

The report emphasises some specific areas where CAP fails to curb emissions. CAP does not seek to limit or reduce livestock – 50% of agriculture emissions – and supports farmers who cultivate drained peatlands – 20% of emissions. Overall livestock emissions have been stable since 2010, while “emissions from chemical fertilizers and manure, accounting for almost a third of agricultural emissions, increased between 2010 and 2018”. Concurrently, CAP continues to financially support and promote the consumption of animal products “the consumption of which has not decreased since 2014”.

Instead, the auditors find, “CAP mostly finances measures with a low potential to mitigate climate change”. The report find that CAP does at least support practices that “may reduce” the use of fertilisers, such as organic farming and grain legumes. However, the auditors found that these practices have “an unclear impact on greenhouse gas emissions.”

ECA made three specific recommendations to address the lack of climate action from CAP

- the Commission takes action so that the CAP reduces emissions from agriculture;

- takes steps to reduce emissions from cultivated drained organic soils; and

- reports regularly on the contribution of the CAP to climate mitigation.

So how is CAP supposed to help with Climate Action?

Farming’s climate impact

Focusing only on on-farm activities, the report opens by stating that ‘agriculture is responsible for 10.3 % of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions and nearly 70 % of those come from the animal sector’. 10.3% strictly excludes farm machinery and heating buildings from the figures, which would add another 2% to the total. Moreover, if imports were to be taken into account, “the proportion of emissions attributable to the production of animal products consumed in the EU increases further” from 70% to 82%,” all while providing just “25% of the calorific intake of the EU.”

The overarching sources of emissions are named as: methane from livestock, nitrous oxide from fertilizer and manure, and carbon dioxide from land use change, in particular cultivation of drained organic soils (peatland) and losses from grassland and cropland more broadly.

Interestingly, overall agricultural emissions “decreased by 25% between 1990 and 2010, mainly due to a decline in the use of fertilisers and in the number of livestock, with the largest fall between 1990 and 1994. Emissions have not declined further since 2010.” Currently there is a 40% emissions reduction target for farming by 2030 in the EU, which may be increased to 55% for 2050.

CAP’s climate elements

Climate action is, since 2014, one of the nine CAP objectives against which the Commission evaluates performance. The Commission estimate just over 100 billion – €103.2 billion, with €45.5 billion for direct payments and €57.7 billion for rural development measures – went towards climate change mitigation and adaptation in agriculture 2014-2020.

Greening – which requires farmers to protect (permanent) grasslands, rotate crops (with exemptions) and protect ecological focus areas – cross compliance – obligations which limits use of nitrogen fertilizers, retain minimum cover and other agricultural practices – and voluntary rural development schemes – agri-environment and climate measures – organic farming, afforestation, advisory services, investment measures (e.g. on manure management) – are the three main ways CAP engages in Climate Action.

Here’s where it starts to get awkward for the Commission. Already by 2016 the ECA had revealed that the Commission was overstating its climate spending on CAP. It put forward 18%, not 26% as “a more prudent estimate”. Nevertheless, “the Commission considered that its climate tracking approach to assess levels of climate spending in agriculture and rural development is sound.”

Despite this possibly exaggerated climate performance, for the coming period, up to 2027, the Commission has increased CAP’s climate ambition. The auditors recommend ensuring CAP Strategic Plans use eco-schemes effectively, to for example, re-wet drained peatlands (note – the new GAEC two may make a contribution here, but, as usual with GAECs, the wording is weak and open to interpretation at member state level).

Assessment – does CAP help with Climate Action?

The substance of the report focuses in on livestock, application of chemical fertilisers and manure, use of land and overall design of 2014-2020 CAP.

Livestock

Livestock emissions haven’t decreased since 2010. The CAP measures do not include a reduction of livestock numbers. Indeed promotional measures funded under CAP seek to increase consumption of livestock products. Reducing livestock numbers would help with lowering emissions from feed, manure and fertilizer.

However the net impact of this depends on changes in consumer patterns, while there is a risk of carbon leakage via imports with reduced production, the auditors warn (this is an important point of comparison with how organic farming is treated in this report, as we will see in part two).

What is sometimes called Jevon’s Paradox gets it own section in the report, described here as the Rebound Effect. The core point here is that efficiency gains can lead to expanded production and increased overall, absolute emissions as a result.

“efficiency gains do not translate directly into lower overall emissions. This is because technological change in the livestock sector has also lowered the production cost per litre of milk, leading to production expansion.”

A small piece of good news – acidification and cooling of manure, impermeable covers of manure stores, and biogas

with manure as feedstock are effective in reducing manure emissions. Several Member States provided CAP support for these practices on a small number of farms, the report adds, though data on this is unclear in many instances too.

However voluntary coupled support (in operation everywhere in the EU except Germany) encourages maintenance of livestock numbers, as farmers would receive less money if they reduced their herd sizes. This is 10% of all direct payments, with livestock supports making up 74% of all coupled supports spending in the EU.

Reductions in or elimination of direct payments, and changes in coupled support would reduce livestock numbers, freeing up more space for afforestation, the report states, citing studies, but again bracketing out leakage impacts. Were farmers to be paid half their direct payments for emissions reductions, this could see a net reduction of about 17% overall.

Fertilizer

There has been an increase in chemical fertilizer use – see figure 14 from the report below – while manure emissions have remained stable.

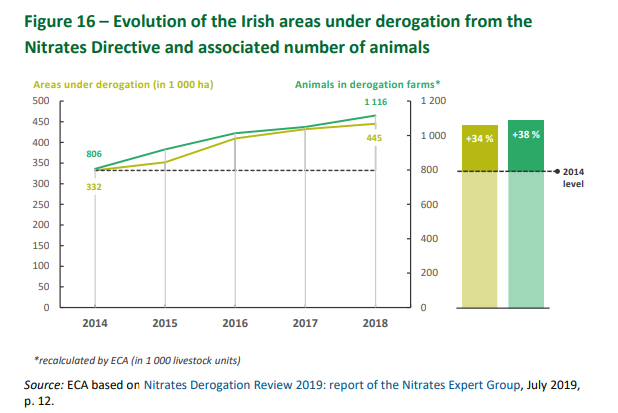

A concern from the 2014-2020 period is derogations from the nitrogen rules. Cross-compliance is supposed to reduce nitrogen pollution into water. Indeed, without the Nitrates Directive, total N2O emissions across the EU in 2008 would have been 6.3 % higher, mainly due to the increase in total nitrogen leaching in ground and surface waters. However four member states – Belgium, Denmark, Ireland and the Netherlands – have obtained a derogation from the Nitrates Directive: “and these four countries are among the highest greenhouse gas emitters per hectare of utilised agricultural area”. Worryingly “since 2014, in Ireland, the area under derogation has increased by 34% and the number of animals in farms with derogations grew by 38%. In the same period, emissions from chemical fertilisers increased by 20%, emissions from manure applied to soils by 6% and indirect emissions from leaching and run-off by 12 %” according to data provided by the Irish authorities (see figure below).

While derogations are accompanied by counterbalances, the report cites a 2011 study that estimated “derogations increase gaseous nitrogen emissions by up to 5 %, with an increase of up to 2 % in N2O.”

Another worrying consideration is that supposed solutions in manure management appear to be problematic. The auditors state that only reduced application of manure was found to successfully reduce emissions, and even technologies like trailing shoe slurry spreading may not help. Trailing shoe slurry spreading and similar “can be effective for reducing ammonia emissions, but they are not effective for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and may even increase them”.

Unlike with overall livestock numbers, CAP does have measures to reduce chemical fertilizer use, the report states. Two practices which have received considerable CAP support, but their effectiveness to mitigate climate change is unclear, are organic farming and grain legumes. Three practices identified as being effective for climate change mitigation, but have received minimal CAP support are forage legumes, variable rate nitrogen technology and nitrification inhibitors.

There is much to say on the treatment of organic farming in this section, so much so that we will dedicate most of the follow up part two article to this topic.

Land use

For land use emissions since 2010, net emissions from cropland and grassland have ceased to decline. Organic soils in particular are worth maintaining, while peatlands contain 20-25 % of the total carbon in EU soil: “when untouched, they act as a carbon sink. However, when drained, they become a source of greenhouse gas emissions” the report underscores. Over the 4 million hectares of drained organic soils, including peatland, are managed as cropland or grassland, result in 20 % of EU-27 agriculture emissions, at just 2% of the total cropland and grassland area.

While the mineral soils of grasslands store carbon, this mitigation effect is more than offset by emissions from cultivated organic soils.

This level of impact, on such a small area of land, means that peatlands become key in the auditor’s thinking and recommendations: “rewetting just 3 % of EU agricultural land would reduce agricultural greenhouse gas emissions by up to 25%” (emphasis added). Some positive developments in some member states are named, as is the new GAEC two on the protection of wetlands and peatlands under the 2021-2027 CAP. However only 2% of peatland areas (600,000 ha in total) have a ban on draining, showing the scale of the task ahead, given that the current CAP pays farmers who cultivate drained organic soils when receiving their direct payments – which is the opposite of restoration.

The reality is that “cultivated drained organic soils are eligible for direct payments while restored peatlands/wetlands might not always be eligible” as the conclusion states later.

CAP does little to protect mineral soils and their stored carbon. Permanent grasslands sequester carbon, and greening in CAP from 2015 aimed to do maintain permanent grass. However, permanent grassland levels are in decline, according to studies cited, due to conversion to arable land. Also in practice permanent grasslands rules have loopholes to allow for ploughing and reseeding, which then emits GHGs. This means the effectiveness of greening stipulations to protect permanent grasslands and their stored carbon “is significantly reduced”.

Another small positive area of performance: environmentally sensitive permanent grassland (ESPG) designates 8.2 million hectares of permanent grassland. “The greening requirement concerning ESPG can better protect the carbon stored in grasslands than the permanent grassland ratio requirement, as under ESPG both conversion of grassland to other uses and ploughing is banned.”

For arable land, there has been “no major uptake of effective mitigation measures.” What could work is the use of catch/cover crops, afforestation, agroforestry, and the conversion of arable land to permanent grassland. GAEC 4 of cross-compliance is designed to cover soil (literally) while the Ecological Focus Area requirement under Greening was also useable for this task. A small increase in the area devoted to catch crops was noted in 2016, which may have been attributable to CAP 2014-2020, from covered 5.3 million hectares in 2010 to 7.4 million hectares in 2016. But, as is so often the case, the member state defines the details, while cross EU data can be difficult to find. Also, for the most part, many farmers were growing catch crops anyway so no improvements were generated.

Both afforestation and agroforestry – which can be effective mitigation measures – saw low take up via rural development funds.

Increased Ambition – but what’s measured, inspected, charged or changed?

Despite climate being one of just nine core objective of CAP, and over E100 billion being supposedly dedicated to climate action, no targets for emissions reductions were set at EU or member state level.

“Member States were not required to set their own climate mitigation targets to be achieved with 2014-2020 CAP funds, and did not do so”

So any impact cross-compliance may have had on emissions goes unmeasured – however, in any case, no significant changes were introduced between the two studied periods. The only targets that Member States reported to the Commission were those for rural development support, “indicating how much funds they intend to spend on climate action, and how much agricultural or forest area or livestock will be covered with this expenditure.”

Inspection rates for adherence to cross-compliance rules are at the incredibly low level of 1% minimum, with tiny penalties – aid reduced by between 1% and 5 % percent, unless infringement is fixable (which results in no financial impact); repeated breaches can see penalties of up to 15%, and “by greater amounts where breaches were intentional.” In 2018, 2.5% of farms were inspected in total. Of these, one in four of the inspected farmers had aid reduced for breaches of at least one of the cross-compliance rules. The report cites the potential of using the Copernicus Sentinel (Satellite) data in future.

As reported by the ECA in 2017, while permanent grassland and ecological focus areas requirements could have increased mitigation, in reality few new mitigation practices were introduced, with farmers opting to declare what they were already doing for the most part. 3.2% of rural funds were climate-targeted in 2014-2020, while “30 out of 115 authorities managing rural development support provided information in 2019 on the net contribution of measures funded with rural development support to greenhouse gas emissions.”

The Commission’s common monitoring and evaluation framework collects data on climate mitigation for each Member State. However this does not provide information on type of practice, their uptake or impact. Data collected is “ad-hoc” and “hampered by a lack of reliable data” and “did not allow the impact of CAP measures on climate change to be assessed” Moreover, the auditors “do not consider that the proposed post-2020 indicators will improve

the situation.”

EU law explicitly applies the polluter-pays principle to its environmental policies, but not to agricultural greenhouse gas emissions. Agriculture neither falls under the EU Emissions Trading System, nor is subject to a carbon tax. The Effort-Sharing Decision puts no direct limits on greenhouse gas emissions from EU agriculture. The CAP also does not prescribe any emission limits.

Recommendations

To conclude, the ECA point to three potentially impactful changes in CAP.

Recommendation 1 – Take action so that the CAP reduces emissions from agriculture.

Recommendation 2 – Take steps to reduce emissions from cultivated drained organic soils.

Recommendation 3 – Report regularly on the CAP’s contribution to climate mitigation.

Each of these needs specifics – targets and timelines in particular, the auditors state. Recommendation 1 needs an actual target, assessment of CAP Strategic Plans, and incentives for reducing livestock numbers and fertilizers. Recommendation 2 needs monitoring, of peatlands and wetlands, as well as incentives to rewet/restore drained organic soils, via direct payments, conditionality, rural development or more. Recommendation 3 needs monitoring indicators, and the assessment of polluter-pays principles along with rewards for long-term carbon removals.

Conclusion

An initial assessment of this report finds that, when it comes to climate action, CAP is an abject failure. Little of the E100billion + spend delivers climate mitigation or adaptation of any of substance,while supposed climate action delivery is exaggerated. Yet there are no repercussions when this is pointed out to the Commission,while, at member state level, the weakening of standards and practices deepens. Some good practices newly supported (e.g. catch crops) were happening anyway, which means the required change isn’t happening fast enough, while in the ECAs view, some measures that deliver benefits do so in an unclear manner. A tiny few areas are working well. But overall, CAP supports in fact retain damaging climate behaviours and generate little climate action. Real targets, real monitoring, real incentives, and, in particular, changes in how we manage peatlands and, relatedly, cultivated drained organic soils, could deliver significantly.

The second in this two part series will further interpret the report, emphasising some strong concerns emerging from what has been presented by the ECA, but also critically assessing what are, it is argued, some contradictions and misunderstandings with regard to organic farming and its role.

ARC coverage of ECA reports since 2018

ARC Exclusive – Auditors Heavily Criticise Commission’s CAP Plans

CAP | Time for Commission to Get Real on Spending, Say Auditors

Auditors – Measures to Stabilise Farmer Incomes have ‘limited effect’

ECA report & 5 Member States Disrupt Commission’s Cosy CAP Communication Plans

CAP | Billions Spent on Biodiversity with Little Impact – Auditors

350,000 Tonnes of Pesticides Sold in EU Each Year – Still No Clear Picture of the Risks

More on CAP

Parliament CAP-itulation | Council-Driven Compromise Deal Scuppers Fair, Green CAP

Hidden Formulas and Agri-Media – Can we Find a Fair CAP in Ireland?

EU COVID-19 Recovery Plan – “No Effective Support” for Greener Ag

CAP Strategic Plans: Support to High-Nature-Value Farming in Bulgaria

Damning Report on CAP Cash in Central and Eastern Europe Released

CAP, European Green Deal and the Digital Transformation of Agriculture

Weaker Eco-Schemes and Pet Projects – Commission Factsheet Unpacked

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.