The EU has funnelled €66 billion into farmland biodiversity since 2014 – and has little to show for it. That’s the conclusion of a special report released on Friday by the European Court of Auditors. The auditors slammed the half-baked targets of the EU 2020 biodiversity strategy, its odd-couple relationship with CAP, lack of monitoring, and some very un-smart spending by the European Commission. A series of recommendations have been made. Louise Kelleher reports.

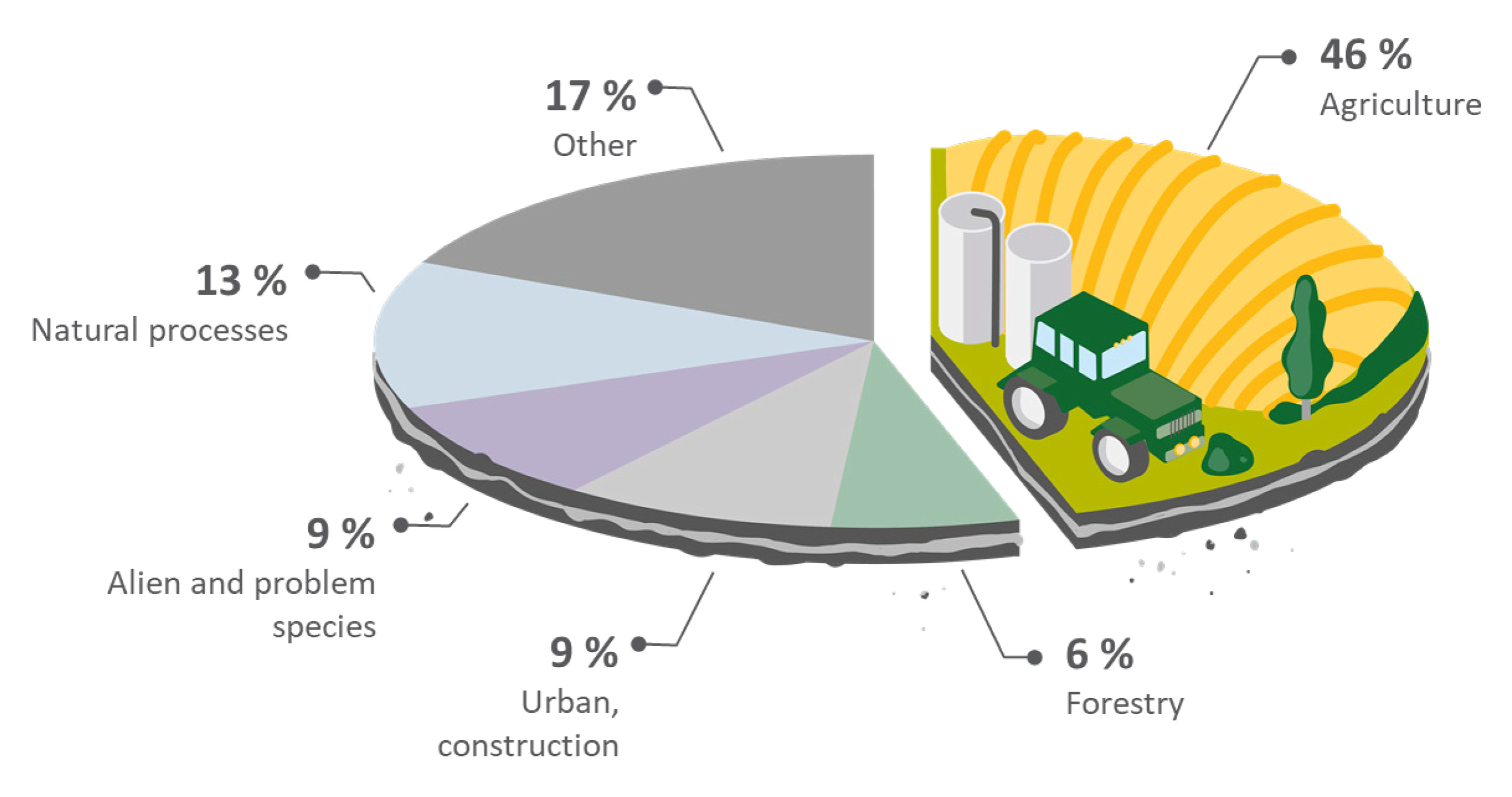

The EU 2020 biodiversity strategy has failed farmland wildlife miserably, says the European Court of Auditors (ECA). Intensive farming remains a main cause of biodiversity loss – despite EU efforts to spend its way out of the crisis.

“Biodiversity on farmland: CAP contribution has not halted the decline” is the straight-to-the-point title of the report released on World Environment Day. In it the auditors sound the alarm on EU agriculture’s continued assault on wildlife populations, implicating CAP funding in various shades of green.

“The CAP has so far been insufficient to counteract declining biodiversity on farmland, a major threat for both farming and the environment,” said Viorel Ștefan, the ECA Member responsible for the report.

Show me the Money

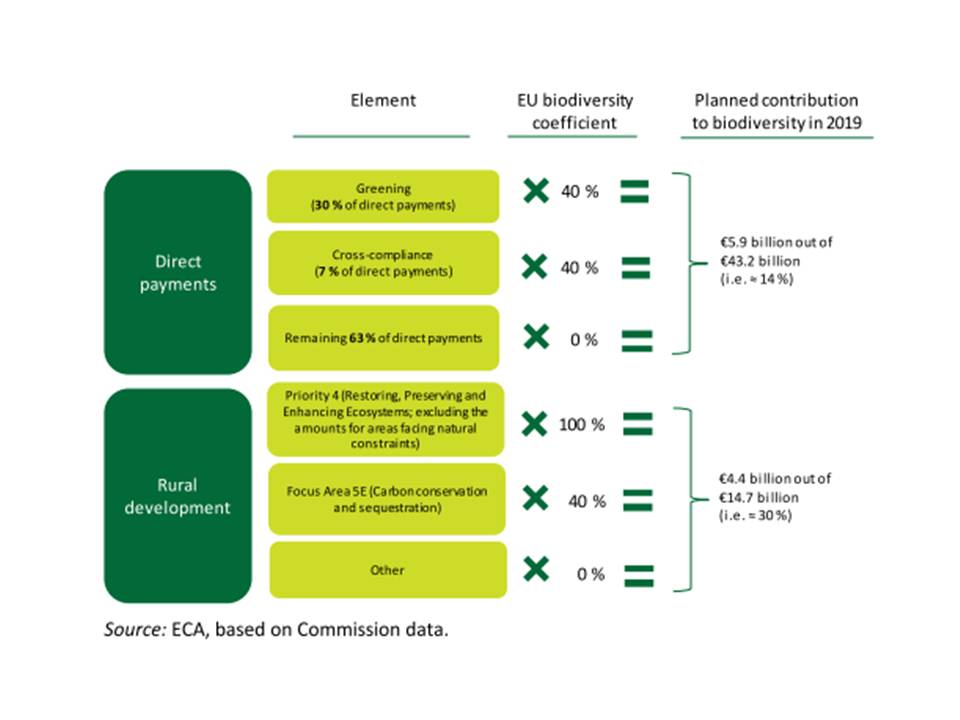

For the period 2014-2020, a total of €66 billion in CAP funding was ring-fenced to halt biodiversity decline on farms across Europe. In 2019 and 2020, as headlines screamed about plummeting wildlife populations, the EU pledged to spend some 8% of its total budget on biodiversity. Most of this spending was to take the form of CAP payments.

But the actual contribution of this spending has been overstated, say the auditors. Most CAP funding has little impact on biodiversity. And the impact of direct payments is tricky to assess.

“Where known, the effect of CAP direct payments – 70 % of EU agriculture spending – on farmland biodiversity is limited” – European Court of Auditors

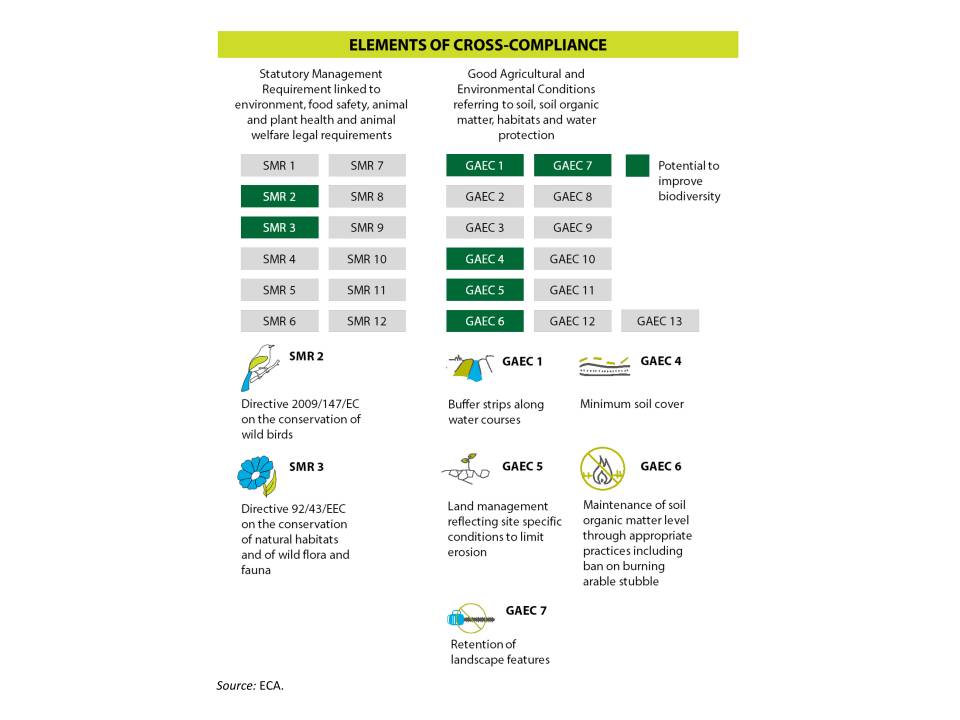

What’s more, the supposed biodiversity benefits of direct payments are based on flawed accounting. The coefficients used by the Commission have been called out as inaccurate by the IEEP and others. For example, the contribution of cross-compliance may be overestimated due to the inappropriate coefficient applied to it.

Some direct payments may even have a negative impact on biodiversity, such as voluntary coupled support, which incentivises the production of specific crops or animals. The Commission does not track and offset expenditure from schemes that may reduce farmland biodiversity.

The Commission is a big spender on biodiversity, but it has little to show for it: there are no targets for this spending, and no reliable way to track the biodiversity benefits.

Not a SMART Target

Because of a lack of measurable targets, it’s hard to assess the performance of the EU 2020 biodiversity strategy. In fact the Commission set itself up for failure when it drew up the strategy back in 2011.

The EU 2020 biodiversity strategy committed to increasing the biodiversity benefits of agriculture and forestry, and delivering a “measurable improvement” in the conservation status of species and habitats affected by agriculture. But it failed to set a SMART target for agriculture: one that was specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound.

Due to this design flaw it’s difficult to gauge progress, chide the auditors. The Commission’s own report on the impact of the CAP on habitats, landscapes and biodiversity, which was published in March, failed to deliver an overall impact assessment due to the lack of monitoring data.

The Odd CAP-ple

From its flawed beginnings the EU’s biodiversity strategy bumbled on into an odd-couple marriage with CAP. There was little coherence between the two, lament the auditors. So poor was coordination between the objectives of CAP and the biodiversity strategy, the issue of genetic diversity was completely overlooked, for instance.

Within CAP, rural development programmes can unlock more biodiversity benefits than direct payments. But indicators are outdated and tend not to focus on results. Within the Common Monitoring and Evaluation Framework (CMEF), biodiversity is lumped into a single indicator relating to acreage. When it comes to assessing the actual effect of rural development policy on farmland biodiversity, there is no indicator for member states to use.

The auditors also found critical data gaps in the Streamlined European Biodiversity Indicators (SEBIs). Overall there are serious shortcomings in monitoring the implementation of the biodiversity strategy at member state level.

CAPable – of much more

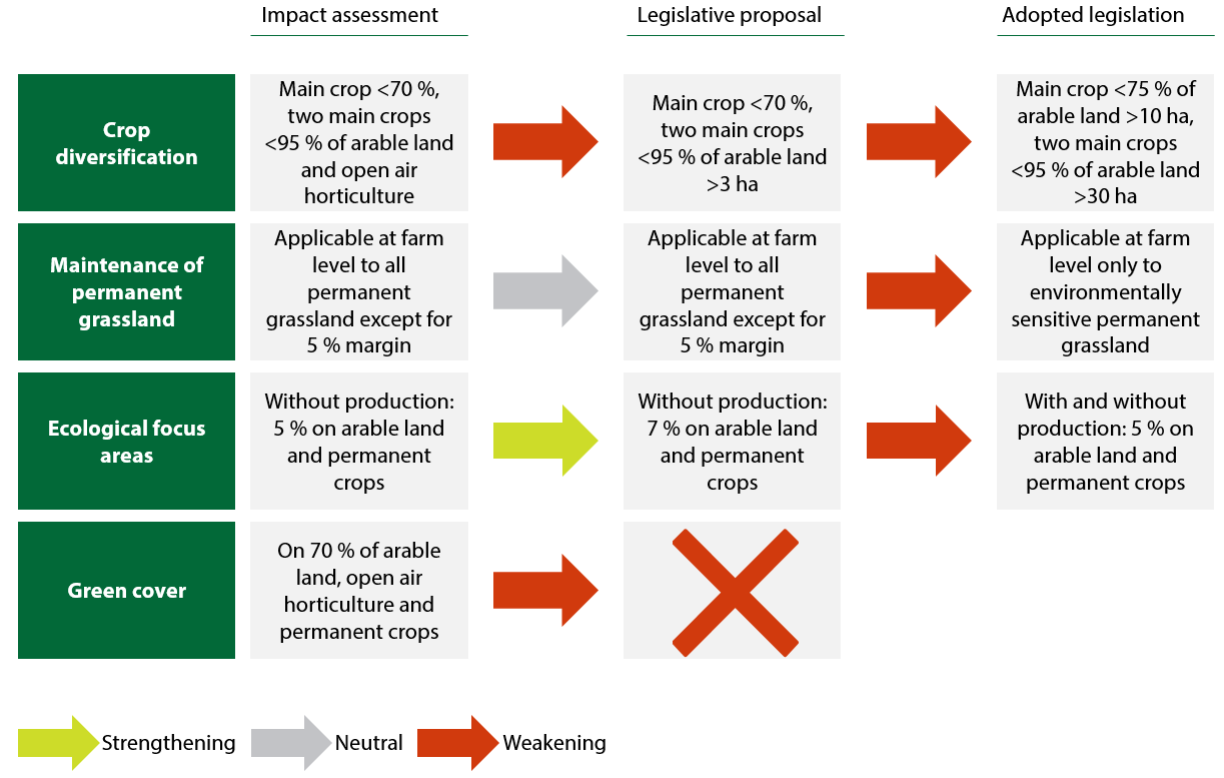

Agri-Environment-Climate Measures (AECM) offer the greatest potential for biodiversity, followed by Natura 2000 and organic farming schemes, note the auditors. The Commission and member states tend to cherrypick “light green” measures that have a lower impact on biodiversity but require less effort for farmers. “Dark green” options such as results-based schemes can have a significant impact on biodiversity but are underused. The auditors found examples of both “light green” and “dark green” measures yielding biodiversity benefits in member states.

Greening measures could be working a lot harder for biodiversity. An example of this is the ploughing of permanent grassland. In Germany and Ireland, for example, farmers can plough and reseed permanent grassland once they have permission – and still meet the permanent grassland requirement. Despite the reduced biodiversity benefits of reseeded grassland, this is common practice, note the authors. In interviews for the audit, 17 out of 44 farmers with grassland had ploughed and reseeded some of their grassland since 2015.

Some elements of cross-compliance also have the potential to deliver more biodiversity benefits (see graphic below). As it stands though, the cross-compliance sanction scheme has no clear impact on farmland biodiversity.

Righting the Wrongs in the New Biodiversity Strategy

In their recommendations, the auditors school the European Commission on how to design a biodiversity strategy that’s fit for purpose. The Commission has accepted all of the recommendations.

Recommendation 1: Improve coordination and design for the post-2020 EU biodiversity strategy and track expenditure more accurately

The auditors suggest some design hacks for the Commission’s new biodiversity strategy:

– Work with Member States to plan the concrete steps to take for farmland biodiversity, and make these steps measurable and time-bound

– Find ways to multiply the impact: join the dots between the new EU biodiversity strategy and the agricultural aspects of Member States’ biodiversity strategies

– Don’t forget about genetic diversity this time: make it a priority in the post-2020 EU biodiversity strategy and in future actions

– Know where the money is going: the Commission must rethink how it tracks the biodiversity budget, to bring it in line with the science, OECD conventions, and changes in legislation.

The auditors give the Commission until 2023 to revamp its new biodiversity strategy.

Recommendation 2: Enhance the contribution of direct payments to farmland biodiversity

Direct payment schemes eat up the lion’s share of the CAP budget (over 70% in 2019) so there’s no excuse for them not to contribute to biodiversity, say the auditors. In the post-2020 CAP the Commission should use all the tools in the CAP toolbox to “deliver more for biodiversity”. The auditors single out direct payments, “enhanced conditionality” and eco-schemes as lagging on biodiversity commitments.

The auditors want to see the full set of CAP instruments delivering on biodiversity by 2023.

Recommendation 3: Increase the contribution of rural development to farmland biodiversity

This is a two-part recommendation. First, the Commission should peg co-financing for various measures to their biodiversity impacts. Second, it should biodiversity-proof the CAP strategic plans from Member States to ensure no opportunities are missed. Rural development interventions and commitments must be “ambitious” and “relevant”, and Member States must make these schemes attractive for both arable and grassland farms.

The Commission should make these changes by 2023, say the auditors.

Recommendation 4: Show the impact of CAP measures on farmland biodiversity

Establish a better baseline for post-2020 CAP: first, develop reliable indicators for farmland biodiversity that can assess positive and negative impacts of CAP. These indicators can then be used to make the various instruments of CAP more effective. Auditors single out the potential benefits of CAP payment schemes and instruments, such as “enhanced conditionality”, eco-schemes and rural development measures.

The auditors give the Commission a tighter deadline for this final recommendation: they want to see CAP instruments working harder for biodiversity by 2022.

The release of the report has been timed to feed into preparations for the 2021-2027 CAP and the new EU biodiversity strategy, and discussions and decision-making at COP15. Meanwhile reactions to the report have been swift and polarised – stay tuned for more coverage this week.

More on CAP and Biodiversity

Farm 2 Fork and Biodiversity Strategies Hold Firm on Real Targets

For the Sake of Nature and the Climate, Europe must not CAP its Ambitions

Commission’s Dodgy Calculations Improve CAP’s Climate Impact

Poking Holes in Farm to Fork: Environmental Groups Seek a Coherent Vision

CAP in Bulgaria Part 2 | BirdLife’s Reform Model – good for farmer’s income and the environment

Ecological Focus Area in Germany: What Influences Farmers’ Decisions?

Rural Dialogues | Peasants of Nature – French Initiative Reconciles Agriculture & Biodiversity