This weekend Hungarians voted Viktor Orbán’s FIDESZ party into a fourth consecutive term in government. What is the secret to Orbán’s continued popularity with rural voters, when he has been breaking promises to them for more than a decade? How will this new parliamentary majority for FIDESZ affect agriculture, farmers and rural areas in the midst of global political and economic turmoil? And will Hungary’s strongman manage to maintain his pro-peasant façade? Analysis by Péter József Bori.

Update: Read this article in Hungarian

Viktor Orbán and his Alliance of Young Democrats Party (FIDESZ) secured their fourth consecutive term in government in the Hungarrian elections on Sunday 3 April 2022. While pre-election polls predicted a narrow race between FIDESZ and the historic opposition alliance Everybody’s Hungary Movement, expectations fell short after Orbán’s party emerged with an overwhelming 2/3 parliamentary majority.

With a 135-mandate dominance, Orbán will face little challenge in implementing his politics and policies. What does this mean for agriculture and what can farmers expect?

Pre-election promises

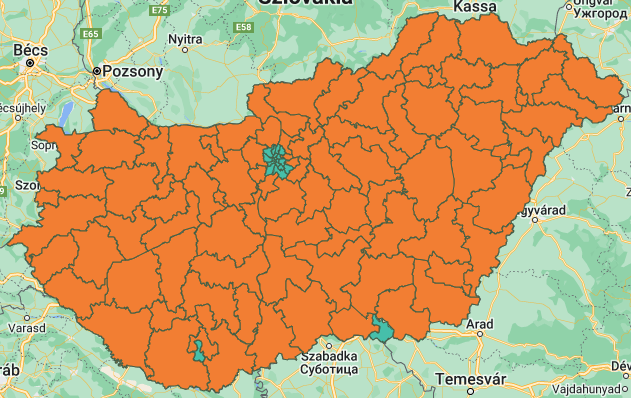

As explained in a previous three-part series on Hungary, Orbán’s strongest support base is located in the countryside. This year it was no different, and indeed nearly every county is painted orange – FIDESZ’s party colour – on the electoral map. Opposition victories occurred solely in a few urban areas.

Although reports of voter fraud and the buying of minority votes raises worries of how clean this election was, Orbán’s ability to maintain such overwhelming rural support is rooted in a much more complex and multifaceted strategy. A strategy that includes pro-peasant propaganda, a near-total control of rural media outlets, the broadcasting of fears and posing as the strongman who will protect Hungarians from all types of imagined enemies (from Brussels to refugees, to, lately, also President Zelenskyy of Ukraine).

Orbán achieved his first majority victory in 2010 riding on the back of a disgruntled countryside, angry for not receiving CAP subsidies and being left to fend for themselves after joining the highly competitive European common market. He promised a pro-European, pro-family farm and pro-diversification program that would lift Hungarian food production to EU standards and fill the countryside with young, prosperous, and happy farming families.

The promise worked at the time, it worked in the next two elections, and it worked this year too. In 2014, just before the elections, Orbán announced that “the countryside is the country’s gold mine”. In 2018, he stated that the agricultural sector is “soaring”.

“It is time to settle Hungary’s debt to the countryside. We must restore the dignity and power that was taken away from rural areas. We must finally give to the Hungarian countryside what it deserves.” – Viktor Orbán in the run-up to the 2022 elections

In November 2021, the government released a generous €3 million package aimed at strengthening the competitiveness of food production, broadening the accessibility of technical innovation for all farmers, and securing steady support for smallholders.

Post-election realities

Orbán’s consistent rural propaganda and policies in the run-up to all his elections in the last decade suggests that the past could provide some indication of what the post-election future holds for rural areas. And that prognosis gives rise to little hope: a quick look at the FIDESZ regime’s rural promises shows that they are just that – promises.

Shortly after his 2010 victory, Orbán backtracked on his progressive rural policy program, forced its creator, József Ángyán, to resign, and embarked on what would prove to be one on the most destructive decades in Hungarian rural history.

Between 2011 and 2013, the government leased out approximately 80 percent of advertised state-owned lands for FIDESZ-friendly oligarchs. In 2015, under the guise of the refugee crisis, over 380,000 hectares of these lands were sold to oligarchs under a thunderstorm auctioning process.

In the process, much needed European agricultural subsidies ended up further enriching some of the country’s wealthiest businessmen, instead of reaching those small and medium holders it was originally aimed at.

The FIDESZ government provided the necessary legislative and political environment for this to happen without much resistance. They raised upper ownership limits and made it easier to amass massive plots through introducing loopholes that allowed large companies to subdivide ownership to individual family members. They embedded institutions that have the ability to withhold CAP subsidies from critical voices and created a politico-institutional environment that favours large landowners and limits the manoeuvring space of small and medium holders.

As a result, today Hungary has one of the most concentrated land structures of Europe, closely resembling that of the 19th–century feudal system.

What’s next?

As was the case in the past three cycles, it is to be expected that Orbán’s pre-election promises will not result in any meaningful improvement to the situation of the Hungarian countryside and farmers in general. The wealthy oligarchs enriched by his rural policies – and partly responsible for his victory – are unlikely to shift gears or direction when it comes to amassing land and European subsidies. The vast rural development grants handed out prior to the elections will likely slowly peter out, and be replaced with an economic package that maintains the bare minimum to ensure rural support for the government. Land concentration will continue.

Yet, Orbán embarks on this 13th consecutive year in power in the midst of global political and economic events where maintaining his pro-peasant façade could prove challenging. Increasing gas prices and dwindling supply due to the Ukrainian conflict have already led to massive shortages in fertilisers. It will also be difficult to maintain the promise of reduced utility costs, when energy prices are soaring across the globe. He will likely need to find new (or old) enemies to blame the worsening situation on.

In addition, labour shortage – which has been one of the main challenges for the sector over the last decade – will likely remain an issue and potentially worsen. Although some officials expressed hope that the influx of labour-capable Ukrainian refugees could, to some extent, alleviate this crisis, it is unlikely that the low wages and tough working conditions will attract much interest from war-fleeing asylum-seekers. In the hours after election results became known, two of the most searched Google terms in the country were ‘emigration’ and ‘working abroad’, suggesting that the trend of brain- and labour-drain to the West will continue.

In sum, it would be a shocking turn of events if, after a decade of marginalising rural communities, another four years of unabated FIDESZ governance would make serious efforts at rural improvement. However, it is precisely now that initiatives which question such embedded rural structures matter the most. Democracy will be played out not in the Parliament, but in the fields of civil society, alternative agricultural initiatives and communities which envision a Hungarian food production that matches the global and local requirements demanded by our changing climate.

More on Hungary

Letter From The Farm | Rasputin The Ram & The Ethics Of Lamb For Easter Dinner