Part I of this background series on Hungary, in the runup to landmark elections this Spring, scrutinised the social, economic and political developments that helped propel Viktor Orbán into power: a disgruntled countryside ravished by unfair distribution of European subsidies, land concentration through privatisation, and general economic exclusion after two decades of anti-smallholder policy, despite the post-socialist era’s promises of individual flourishing.

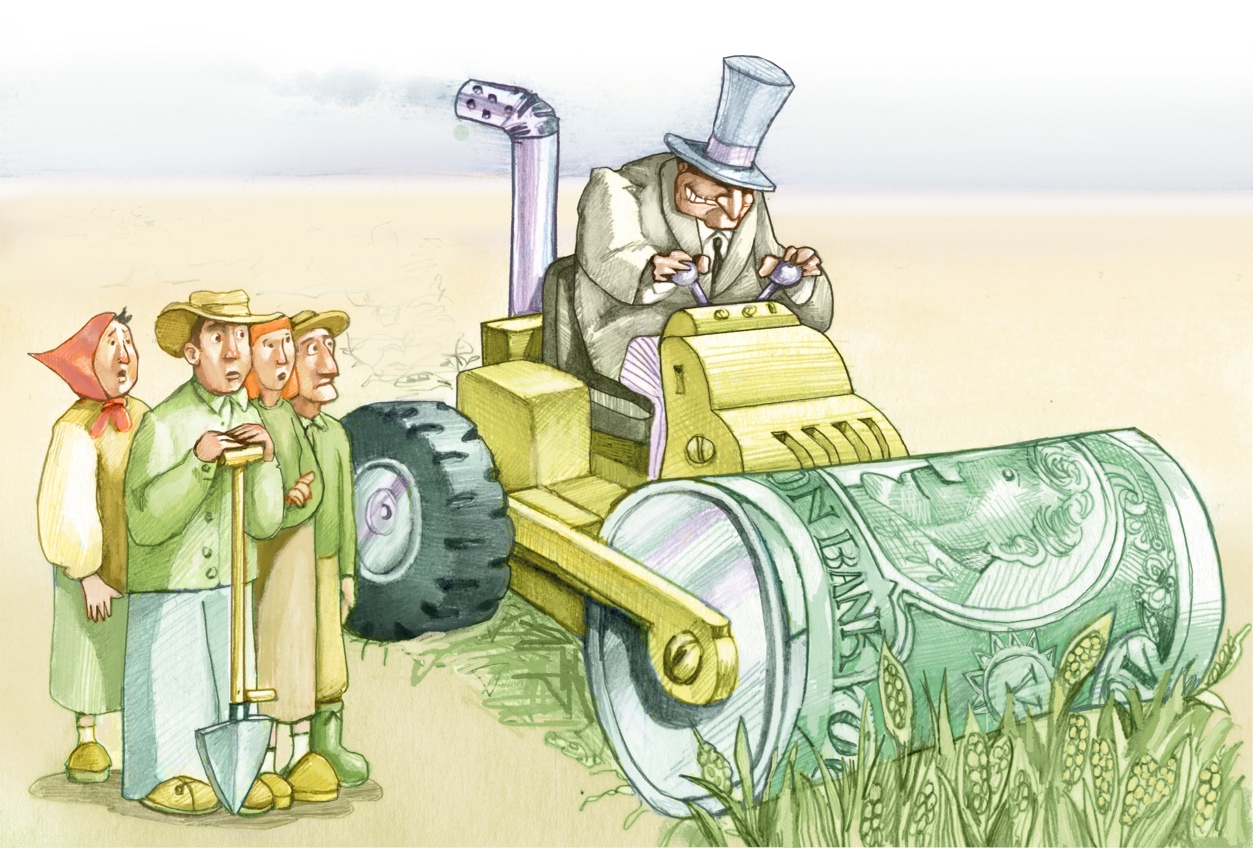

The second installment explains how Orbán and his FIDESZ party backtracked on their promises after their election in 2010. What followed is a decade of land grabbing, destructive agricultural transformation and the alienation of Hungary’s last smallholders – all while maintaining the image of a pro-peasant government. Original research by Péter József Bori and Noémi Gonda.

The date was April 11, 2010. Unlike five years earlier, there were no angry farmers in the streets of Budapest, nor were there any tractors parked in front of the Parliament. Instead, a few blocks away, at Vörösmarty Square, thousands of supporters of the Party Alliance of Young Democrats (FIDESZ) listened to a speech by leader Viktor Orbán, who had just won the parliamentary elections with an overwhelming two-thirds majority.

Prior to the 2010 elections, Orbán had promised to tend to the grievances of a disgruntled countryside and there were signs suggesting he would do so. He had brought in representatives of the Alliance of Hungarian Farmers (MAGOSZ), provided them with parliamentary mandates in the 2006 elections and tasked them with drafting a pro-European, pro-family farm and pro-diversification rural strategy.

In this second part of this series we explain how Orbán and his FIDESZ Party backtracked on these promises – or worse, continued on their premeditated plan – following their election in 2010. What followed is a decade of land grabbing, destructive agricultural transformation and the alienation of Hungary’s last smallholders. And all of this while maintaining the image of a pro-peasant government.

Land grabbing and “land peace”

A key term to understand here is ‘land grabbing’. The term is commonly applied when looking at harmful and unfair land acquisition in the Global South. Often, transnational companies (think, Bayer) or countries rich in capital but poor in land and water resources (think, the Gulf States), acquire land in countries with abundant resources, but little capital (think, Ethiopia). While sold to the public as the necessary means to development, these acquisitions regularly violate Human- and Indigenous rights and have harmful social and environmental impacts. The process often enriches these countries’ political elites, through bribes and lobbying.

After 2010, land grabs in Hungary occurred with slightly different methods and for different purposes. Most lands were leased and sold to wealthy Hungarian investors with a political objective: to enrich the regime’s political and economic supporters. As such, a somewhat symbiotic relationship exists between the economic elite and the regime. The former relies on the government for its wealth acquisition through corrupt public procurement deals and speculation through land auctions; while the latter depends on the economic elite that owns most rural news sources to distribute its pro-peasant and fear-mongering propaganda.

In 2020 Viktor Orbán unassumingly described this symbiosis when he said that ‘today, in Hungary, there is land peace’. So how exactly did he achieve “land peace”? First, between 2011 and 2013 the government facilitated a tender to lease out state-owned land whose 20-year agreements with previous lessees were coming to an end. Instead of making these plots available to local farmers, approximately 80 percent of all advertised lands landed in the hands of government-friendly oligarchs. Official tender documents were classified and upper lease limits were raised from 300 to 1200 hectares.

In a tragic symbolic move, the lease of Kishantos – an organic state farm and folk high school that had promoted organic agriculture for more than 20 years – was auctioned off, ploughed and sprayed with chemicals by the new landowners. As a result of these unfair auctions, József Ángyán, the professor responsible for FIDESZ’ progressive Rural Strategy, resigned as secretary of state. Ángyán has since devoted himself to uncovering subsequent land grabs and exclusionary land deals.

The culmination of these political land grabs was the intensive land privatisation programme of 2015 that announced the auction of 380,000 hectares of state-owned land. Once again sold as a strategy to attract young families to the countryside, the auctions mostly favoured large landowners. Lessees of land were given priority in making offers, which proves that the 2011-2013 tenders that favoured oligarchs were preparing for this move; maximum limits per individual were raised from 1200 to 1800 hectares, meaning a family of multiple landowners could amass many thousands of hectares; and often the asking price of plots was set at staggeringly high rates that local farmers couldn’t match.

The making of a modern day feudal system

Under the cover of a deliberately chaotically managed refugee crisis, in 2015, 80 percent of auctioned lands were bought by FIDESZ interest groups, large agro-industries and foreign investors. As a result, today, Hungary has Europe’s third most concentrated agricultural land structure: almost 32 percent of all plots are over 500 hectares and are owned by 0.3 percent of all landowners – closely matching numbers from 19th century feudal Hungary. Since 2010, the number of farms has shrunk by one third, from 351,000 to 234,000 in 2022.

Adding to the complexity is the existence of so-called integrators – large companies owned by the country’s wealthiest businessmen – which supply farmers with pre-harvest input (i.e. manure, pesticides, seeds), only to buy back their produce post-harvest, often at unfavourable prices. These contracts regularly leave farmers in inescapable dependency.

Oligarchs, organigarchs and the European Union

That such an agrarian system doesn’t favour small family farms and the countryside is clear. The existence of absent farmers (individuals who own land in multiple areas with no presence in the localities) means that most of this land is under intensive and industrial-scale agricultural use – or speculated upon, waiting to be sold at high prices. Single crops such as wheat and sunflower dominate the landscape, when in fact the Carpathian basin could play host to rich and diversified food production.

Though there is an increasing presence of organic farms, these are similarly owned by wealthy oligarchs – or, more precisely, “organigarchs” – and the produce is primarily for export. Small farmers are restricted to local markets, but even there have to compete with cheap imports.

Unfortunately, the European Union plays a crucial role in facilitating such a system. Land grabs with speculative purposes that began in the late 1990s and accelerated under Viktor Orbán’s regime are facilitated by Single Area Payments. As national governments decide the distribution of CAP subsidies, autocratic regimes such as Hungary and Poland exclude precisely those farmers that the CAP is supposed to protect.

In April 2022 elections will take place in Hungary. In preparation, Viktor Orbán has pulled out the proven script and announced that large amounts of subsidies will be distributed to the countryside over the next months to support a dynamic, young and family-farm based rurality. By constantly broadcasting fears of a migrant invasion, George Soros, LGBTQ+ school propaganda and other imagined enemies onto the televisions of rural Hungarians, Orbán masks the fact that the biggest enemy of the countryside has been sitting right inside the Parliament, holding a two-thirds majority.

Yet, all hope is not lost. In Part III of this series we look at the shimmers of light that emerge in the face of authoritarian populist regimes. Agricultural initiatives that are able to bypass these top-down barriers are mushrooming in all corners of Hungary. We will discuss how Community Supported Agriculture, permaculture and other alternative farming and community practices could redefine Hungarian food production and, by extension, democracy.

Noémi Gonda is a researcher at the Department of Urban and Rural Development at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. She holds a PhD from Central European University. She is currently doing research on justice and conflict resolution in resource management as well as on the linkages between natural resources depletion and authoritarian populist political regimes. Her empirical research field sites are in Nicaragua and Hungary. Previously to becoming a researcher, she worked in Nicaragua, Honduras and Guatemala with smallholder farmers, indigenous groups and international organisations. Noémi is particularly interested in exploring how radical social and environmental transformations towards justice and equity can emerge, and the role of scholar-activists in supporting the emergence of such transformations.

Noémi Gonda is a researcher at the Department of Urban and Rural Development at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. She holds a PhD from Central European University. She is currently doing research on justice and conflict resolution in resource management as well as on the linkages between natural resources depletion and authoritarian populist political regimes. Her empirical research field sites are in Nicaragua and Hungary. Previously to becoming a researcher, she worked in Nicaragua, Honduras and Guatemala with smallholder farmers, indigenous groups and international organisations. Noémi is particularly interested in exploring how radical social and environmental transformations towards justice and equity can emerge, and the role of scholar-activists in supporting the emergence of such transformations.

Péter József Bori is an independent researcher with degrees from the University of Copenhagen in Denmark and the University of Sussex in the United Kingdom. His research focus is on post-Soviet European rural development and the appropriation of environmental and rural narratives by authoritarian populist regimes. He is interested in the emancipatory potentials of rural regions and how small-scale agricultural initiatives (i.e. Community Supported Agriculture, permaculture) can produce new avenues towards democratic reform.

Péter József Bori is an independent researcher with degrees from the University of Copenhagen in Denmark and the University of Sussex in the United Kingdom. His research focus is on post-Soviet European rural development and the appropriation of environmental and rural narratives by authoritarian populist regimes. He is interested in the emancipatory potentials of rural regions and how small-scale agricultural initiatives (i.e. Community Supported Agriculture, permaculture) can produce new avenues towards democratic reform.

More on Hungary

Letter From The Farm | Rasputin The Ram & The Ethics Of Lamb For Easter Dinner

More on rural populism

Quietness & Adaptability – Ukrainian Peasants’ Responses to Land Grabbing & Agribusiness Expansion

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.