To mark the publication of the Meat Atlas 2021, we are republishing a selection of our favourite articles. In this one, Peter Birke brings attention to poor labour conditions in the global meat industry. The pandemic has put a spotlight on this issue, but it is by no means new. EU food trade unions call for a bloc-wide response.

The MEAT ATLAS 2021 is jointly published by Heinrich Böll Stiftung, Berlin, Germany Friends of the Earth Europe, Brussels, Belgium Bund für Umwelt und Naturschutz, Berlin, Germany. Republished under Creative Commons (CC BY 4.0)

Covid-19 outbreaks in abattoirs and processing plants are just the latest in a long list of problems in the meat industry. Low wages, hard work, and precarious employment are the price that workers pay to supply us with cheap meat. The industry is attempting to dodge its responsibility to provide decent conditions for its staff.

By Peter Birke

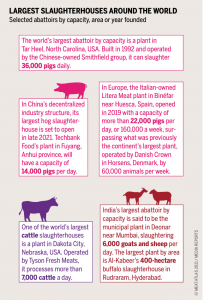

In early 2020, it emerged that over 200 of the 3,700 employees at Smithfield in Sioux Falls, one of the biggest pork processors in the US, had been infected with Covid-19. After an intervention by the federal government, the plant was classified as a “critical infrastructure industry” and was not closed immediately on the grounds that a shutdown would lead to supply shortages. It was only after 700 workers had contracted the virus that production was finally halted for three weeks.

Read, Download the Meat Atlas 2021

Sioux Falls was no exceptional case. Mass infections of workers occurred in numerous slaughterhouses and meat processing plants around the world. Tens of thousands of workers in the Brazilian meat industry were infected, and dozens died in the first wave of the pandemic. Poultry plants belonging to the world’s largest meat companies, JBS and BRF, were criticized for refusing to provide their workers with the necessary equipment to protect them against infection. The authorities in Rio Grande do Sul linked one-third of all Covid-19 cases to local cold-storage facilities. In Mato Grosso do Sul, one-quarter of the workers in a cattle abattoir owned by JBS tested positive for the virus. At the main factory of Tönnies, Germany’s biggest pork processor, more than 1,500 of its 6,100 staff were found to be infected.

The Covid crisis has shined a spotlight on the poor working conditions in the meat-processing industry around the world. A long list of factors has contributed to the spread of the virus in the industry, including a lack of social distancing, poor housing conditions for workers, a lack of inspections, cold temperatures, and insufficient ventilation. Management, on the other hand, likes to blame the workers for the disease outbreaks. Even when there were cases of tuberculosis in German plants in 2018 and 2019, managers denied responsibility. During the Covid-19 crisis, politicians and managers have used racist stereotypes of migrant workers to “explain” the infections: the “living conditions of certain cultures” are supposed to make workers want to live close together.

Criticism of the labour conditions in the meat industry is by no means new. In many countries, slaughterhouses employ people whose residence status forces them to accept low wages and poor working conditions. In many parts of Europe, labour turnover rates are correspondingly high. A large proportion of the staff in the meat sector are cross-border or migrant workers from both within and, increasingly, from outside the EU. The work is frequently physically demanding with repetitive hand movements, excessive working hours and exposure to health hazards.

A report by EFFAT, a European trade union federation, warns that many workers are employed through temporary work agencies or subcontractors that enable the meat plants to escape liability. In some countries, the subcontractors operate as bogus cooperatives, with the workers classified as self-employed. The practice of “posting” workers – employing workers in one country but having them perform the work in another – still occurs, though it is becoming less common. “Letterbox” companies are also frequent. These have a mailing address in one country but conduct their business in another. Such tricks enable employers to evade or circumvent stricter regulations concerning remuneration, social security and taxes in the host country.

The enormous expansion of meat production facilities and abattoirs in recent years has been accompanied by rising numbers of migrants working in the industry. It is also marked by the internationalization of corporate structures. For example, Smithfield, the largest pork producer in the Western world with over 100,000 employees, is now part of WH Group, which is headquartered in Hong Kong. JBS, a Brazilian beef producer firm with over 200,000 workers, has been active in the US market for years. In the USA, the deterioration in working conditions has been accompanied by fierce disputes. Between 1994 and 2008, Smithfield was the scene of a long-lasting battle over union rights and decent working conditions. Even though this struggle ended in defeat for the workers, demands for better labour rights, social rights and secure residence are still on the table.

To put an end to the poor working conditions in the meat industry, European food trade unions are demanding that the EU create a legally binding instrument to ensure that employers are jointly liable throughout the whole subcontracting chain. This should provide for sanctions, back payments and compensation if the industry does not respect labour laws. A European solution is needed because the sector is mobile. The boom in the German meat industry is rooted in the shift in production from Denmark and the Netherlands, where wages are higher and collective agreements generally protect workers better.

More

Covid19, Meat Processing Plants and the Limits of the Intensive Farming Model

The True Cost of Britain’s Addiction to Factory-Farmed Chicken