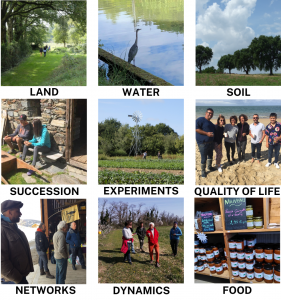

Producing and selling locally is a shared value. Rural territories are defined not by administrative borders but by economic concerns. That’s what we heard on the ground from the farmers and other rural actors we visited in France in 2021 and 2022. On the topic of the place of agriculture in territorial dynamics, several participants defined their territory as where they sell their products. The broader community is demarcated by commercial exchanges, or even potential channels for distribution. Last in a four-part series analysing the hot topics around transition, by the Rural Resilience project team.

Background

For almost a century, the so-called primary sector (agriculture) lost jobs and manpower to industry and services, in the name of ‘development’, ‘modernity’ and the balance of trade, with the export of agricultural products and import of manufactured goods and petroleum products. After more than half a century of the CAP, agriculture still has an economic function in terms of jobs that cannot be outsourced, maintaining local businesses, and ensuring living territories. The role of farmers in the territory is back in the spotlight as local authorities, citizens and other actors work to support sales of local products and to develop local distribution channels.There is no magic wand: behind these efforts to support local are a variety of networks, both formal and informal.

Formal networks, shaped by history

Agriculture today involves a diverse range of actors. This plurality is essential to build the resilience of rural territories.

Institutions

In France, rural development is decentralised to a whole network of state-run organisations. At regional level, the Ministry for Agriculture and Food Sovereignty is represented by the regional directorates (Directions Régionales de l’Alimentation, de l’Agriculture et de la Forêt, or DRAAF) and at departmental level (Direction départementale des territoires, or DDT). The Chambers of Agriculture are crucial for new farmers:

“What allowed me to move forward was working with the Chamber”

Sébastien Blache, mixed farmer

However, the majority of the farmers we spoke to are critical of the work carried out by these organisations. They note divisions between small producers and large producers, and a lack of adaptation to new agroecological practices and other developments, which results in orders that may be contradictory or inappropriate to the daily lives of farmers and their customers. For the majority of project participants, contact is limited to the strictly necessary, regulatory aspects.

Trade unions

The majority farmers’ union in France is the FNSEA, aligned at European level with COPA-COGECA. However, most of the farmers we met belong to Confédération paysanne, the French chapter of La Via Campesina and advocate for the day-to-day concerns of peasant farmers on the ground. This representation for small farmers is essential for reporting to state institutions (such as the SAFER regional development agency – Société d’aménagement foncier et d’établissement rural), even if the debates can bring divergent points of view.

Networks for getting work done

The farmers we met are actively involved in groups that help them to limit investments in equipment, to connect with other farmers, and to share information and new ideas for collaboration: the CUMA machinery cooperatives, replacement associations, and associations that manage processing tools (cooperative slaughterhouses and other processing facilities, AMAPs (community supported agriculture).

The CUMA cooperatives are places where all types of farmers come together, regardless of their opinions: it is a place of solidarity and working together, especially when it comes to planning and decision-making. In the village of Campbon, the local CUMA branch plans to create a workshop for seeds and seedlings.

Farmers also belong to groups where they can exchange and learn, with training and support from experts on technical matters and more general issues. Other organisations often cited by the farmers we spoke to are ADDEAR (Association for the Development of Agricultural and Rural Employemnt) and CIVAM (Centres for Initiatives to Value Agriculture and Rural Areas). For example, vegetable grower David Peyremorte has leaned on these groups for training and exchanges on the working conditions of employees, and for support when starting his farm.

The geographic spread and the role of these support structures varies in different parts of France. The plurality of unions is a laudable achievement for French farmers over the last 50 years.

Less formal networks – incubators for the future ?

A changing patchwork of actors engaged in agriculture

Numerous structures work on rural, food and farming issues, contributing to the evolution of territories: non-profit associations, rural development advisors, researchers, schools, INRAE (French research institute for agriculture, food and environment), community groups, territorial agencies, start-ups. Often there is no coherence or communication between these various structures, resulting in missed opportunities for collaboration. While these networks weave ties between territories and between sectors, there can be a certain amount of competition i.e. coopetition between networks, as well as between territories. This raises questions around the aims of these networks, their funding (in some cases, calls for proposals can encourage the grouping of initiatives) and the visions at work in the territories: who should be at the service of whom and for what?

Family, friends and neighbours

Informal networks of family, friends and neighbours are an essential part of rural life, based on mutual aid: helping out neighbours and friends, working together at markets, spreading manure on a neighbour’s farm, tool swaps. These nameless networks are nonetheless important to build community and spark ideas.

In the end, the co-existence of these networks raises many questions:

- Are there spaces for debate and exchange (despite the omnipresent workload)?

- How to reconcile work and involvement in networks?

- Since each initiative is specific, how to ensure that each one is properly represented?

- Is there a new model to invent? To be re-invented? (like the maintenance of the commons in the rural world)

- Should volunteer work be ‘paid’ and how?

A good illustration of territorial dynamics in practice is the shared maintenance of hedgerows and paths.

Networks at work: Taking care of the landscape

Farms provide a collective service to municipalities by maintaining hedgerows and paths and shaping the landscape of the area. The municipality alone would not be able to provide this maintenance. Some municipalities put in place supports in recognition of the work. In the Deux Sèvres department, an environmental charter was established:

“When I was a [municipal] councillor, we set up an association to create a charter on hedgerow maintenance. It wasn’t great that farmers were living on subsidies, but what really deserved a subsidy was the maintenance of hedgerows on paths. All the inhabitants benefited, but it was the farmers who did it. So we set up a charter and if the farmers respected the charter, they were compensated per hour worked”

– Ludovic Boulerie, farmer-baker

The municipality of Campbon (Loire-Atlantique) asked farmers to collectively reflect on a better distribution of land in order to reduce their impact in terms of transport, with a view to preserving natural resources, hedgerows and biodiversity. This is in contrast to the large-scale land consolidation carried out by the French state.

The non-profit association Fermes Paysannes et Sauvages also works to develop and restore biodiversity to farmland.

In upland areas, farmers play an essential role in nature conservation, with practices such as land management and turning out to pasture.

“It’s about the environmental practices of humans, their relationships to nature and the environment, to the world in which they are evolving.”

– Claude Veyret of the non-profit Ecologie au Quotidien

Rural communities are shaped by complementary networks

As these farmers describe the networks that contribute to their activities, it conjures up the communities where they live, where these socio-cultural relationships play out.

“People drive the economic, social and cultural dynamic of the territory” – Claude Veyret

A rural community is rarely defined by administrative borders. For all the farmers participating in the project, the local community is important, and getting involved to keep their territories attractive and alive is essential. It’s about social ties and a sense of belonging.

“The territorial approach that gives pride to its inhabitants”

– Hugues Vernier, former head of agriculture for the Val de Drôme agglomeration of municipalities

This community extends to visitors of all ages as farms open their doors and host events accessible to all.

Don’t miss the rest of the Rural Realities series:

Part 1 – Feet on the Ground in the The Battle for Land

Part 2 –Succession – Passing It (All) On To The Next Generation

Part 3 – Testing Grounds for Wellbeing

In 2023-2024, “Nos Campagnes en Résilience” embarks on a new phase of joining the policy dots while continuing to nurture what we have built together. Now renamed the Rural Resilience project, the scope has widened from France to the broader Europe. To learn more, visit the project page, follow us on Instagram, LinkedIn and Facebook.

Visit the Rural Resilience project page

Read ARC2020’s findings from the field in France, 2020-2022

More on the project

Rural Realities | Succession – Passing It (All) On To The Next Generation

Cultivating The Future Together – ARC’s Rural Resilience Gathering in France

France | Meet The Farmer-Bakers Proving Their Skills – part 2

Cross-Pollinating Resilience From Portugal: Nos Campagnes en Resilience in Plessé