By the Rural Resilience project team

The countryside is a nice place to live. Farmers are happy. That’s what we heard on the ground in the cooperative farms we visited in France in 2021 and 2022. One thing these farms have in common is a focus on collective wellbeing: farmers are innovating and experimenting to improve quality of life for themselves and their communities. Yet these experiments go under the radar at national and European level, and need supports to weave ties between actors and sectors. Part three of a series analysing the hot topics around transition, by the Rural Resilience project team.

Background

Faced with changes in society, climate and geopolitics, we are all vulnerable. This vulnerability calls for ongoing adaptation, questioning of how we work and how we live. For rural territories, quality of life is a lever for development. Rural society is imagining new ways of functioning, in which every person has a place, and their needs and wants are respected.

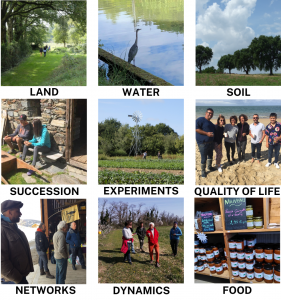

“Nos Campagnes en Résilience” (now the Rural Resilience project) looked at agroecological transition initiatives in France through a socio-ecological lens. We chose to research cooperative farms known as GAECs (Groupement Agricole d’Exploitation en Commun). This legal structure is interesting for several reasons: GAECs are rooted in practices (both conventional and non-conventional agriculture), and played a social role in agricultural and rural France in the 1980s and 1990s by working for gender equality in the running of a farm.

Through this entry point, we sought to find out how GAEC cooperatives were now contributing to other social and ecological issues. Rural society is changing in terms of its relationship with work, living environments and quality of life. Official experiments have made some progress – such as the ‘Youth Guarantee’ (Garantie Jeunes) deployed over several years in experimental stages. Yet individual ultra-local initiatives remain the best way to find and test solutions.

Community and solidarity

The statistics are stubborn: poverty remains more prevalent in so-called rural areas. Some farmers are involved in social policies for vulnerable people, with donations to the Restos du Cœur soup kitchens, commitments to social security for food, or solidarity shops… A participation in local life to try to reduce inequalities. Au Maquis, a non-profit in Luberon, is experimenting with bringing to the farm people from working-class neighbourhoods in a nearby city:

“We grow food with and for people in food insecurity. We go to Cavaillon to collect the people, and while we work on the farm, a team prepares the meal at the village café. Then we eat together” – Maud, Au Maquis

Together these actors contribute to a more harmonious and solidarity society. However, this raises questions, especially when the farmers sell their products at very low prices in order to participate in the collective effort:

“We’re aware that it’s a crutch for a system that doesn’t work. If we sell at a lower price, we’ll be in a precarious situation and going to the solidarity shop because we won’t be able to make a living from our work. It doesn’t make sense to think of the social economy like that.”

This social issue remains unresolved: these ultra-local experiments are sticking-plaster solutions.

Wellbeing on the farm

Farming has changed over the last 30 years. The cooperative farms we visited are life-size laboratories for agroecological practices which began as experiments and are now generalised.

No more long hours seven days a week: work on the farm is organised to allow for free time – for leisure, volunteering, or family time.

“One-third sleep, one-third leisure, one-third work. For your social life, you have to free up time. In farming you can have one-third leisure time if you work collectively.” – Pierre Gachet, market gardener

Work-life balance is essential for the farmers we spoke to. It’s a dealbreaker when joining a cooperative farm or taking over land – on par with earnings. This new perception of agricultural activity leads to a more collective form of work. The functioning of the farm is carefully designed and regularly re-assessed in keeping with the skills and preferences of the farmers.

“We gave ourselves references according to the desires and preferences of each person” – Ludovic Boulerie, farmer-baker

This sort of organisation calls for new skills.

“We all try to be more versatile to have more time off, a personal life” – Fanny Serralongue, mixed farmer

When everyone on the farm has polyvalent skills, the result is autonomy (notes Stéphane Airault), mutual trust and shared responsibilities (say Marion and Benjamin Henry). This eases the mental burden and improves everyday life.

Ergonomics is a concern, as farmers seek to improve working conditions in their tasks:

“We don’t want to hurt ourselves anymore, so I think we’ve had a lot of discussions over the past year on how to gradually improve ergonomics” – Fanny Serralongue, mixed farmer

These farmers are negotiating and sharing organisational systems. They are pooling skills to serve common projects, with an emphasis on quality of life. The innovative systems they have created, by definition vague, lack recognition and resonance at national and European level. The reward? “Live to an old age and in good health”, says Stéphane.

Fair earnings for farmers

For the majority of the 40 farmers we visited, income comes from direct sales of their products. This gives them a degree of control over the price… a price they describe as fair. But what is a fair price? An experiment carried out with the Cooks Alliance (Alliance des cuisinier.e.s) in the West of France found that the key variable was, not surprisingly, the cost of labour.

Among the farmers we met, for some, earnings matter little; others require higher earnings to meet greater overheads. How can this variable be taken into account in the price? The question remains open.

Nevertheless, the way in which the question of price is broached with consumers seems to have an impact: it is important to educate the farm’s customers. Communication on price is essential to improve understanding of the structure of operating costs. Beyond a fairer income, direct sales are an opportunity for these farmers to meet and interact with consumers.

Many of the farmers have been involved in AMAPs (community supported agriculture) since the early days of their farm. The AMAP system ensures cash flow for farmers, as well as help with certain tasks on the farm. A lot of planning is involved: “In the AMAP, you commit to providing 5 or 6 different vegetables each week in the basket, which is very demanding in terms of planning,” explains market gardener Vincent Peynot.

Since late 2021, these farmers have seen a drop in direct sales, with in some cases a loss of up to 30% of turnover. This forces farmers to diversify production, diversify their activity, and create new sales channels: not to put all their eggs in the same basket. Additional earnings can come from farm stays, or educational or community-related activities, as we see particularly in the Drôme region. Because of the personal investment in these activities, they also increase workload.

Earnings can be affected by debt, and good management of the farm’s finances. Modest earnings are complemented by benefits in kind: fresh produce from the farm, bartering between farmers at the end of the market, a house on or near the farm, use of work vehicles.

A social future is the only possible future. These actors are stepping up in the name of collective wellbeing, and teeming with ideas to be put to the test. Their experiments, however formal or informal, are spotlighting connections, and making space for solidarity and mutual aid at farm or community level. This sharing of ideas and energy takes time: to build ties and to master constraints. It also requires facilitators to connect and build bridges between sectors.

Don’t miss parts 1 and 2 in the Rural Realities series: Feet on the Ground in the The Battle for Land and Succession – Passing It (All) On To The Next Generation.

In 2023-2024, “Nos Campagnes en Résilience” embarks on a new phase of joining the policy dots while continuing to nurture what we have built together. Now renamed the Rural Resilience project, the scope has widened from France to the broader Europe. To learn more, visit the project page, follow us on Instagram, LinkedIn and Facebook.

Visit the Rural Resilience project page

Read ARC2020’s findings from the field in France, 2020-2022

More on the project

Rural Realities | Succession – Passing It (All) On To The Next Generation

Cultivating The Future Together – ARC’s Rural Resilience Gathering in France

France | Meet The Farmer-Bakers Proving Their Skills – part 2

Cross-Pollinating Resilience From Portugal: Nos Campagnes en Resilience in Plessé

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.