Taxpayers have a right to demand value for money from agricultural subsidies. But does this merit placing farmers under continuous surveillance? Farmers can struggle to reap the benefits of new digital tools that add to rather than ease their workload. Czech farmer Terezie Daňková relates her experience with the demands of the new digital order, and proposes an intergenerational solution.

Agriculture is an inherently conservative industry. If you were to ask the man in the street which field of human activity he considers most affected by digitalisation, he would probably not choose agriculture. However, digitalisation is rapidly entering this sector too.

I am not going to talk about the revolutionary technologies that allow cameras to determine the health of each plant and apply the exact amount of fertiliser to its roots. Nor am I going to praise collars capable of detecting the function of an animal’s digestive tract 24 hours a day.

I will talk about how digitalisation is affecting farmer-government communication. When I refer to the state administration, I am referring primarily to the Czech State Agricultural Intervention Fund (SZIF), which administers agricultural aid from the European Union and the Czech Republic. Then there is the Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry of the Environment, the State Veterinary Administration and other institutions.

Continuously monitoring farmers

It is well known that agriculture is a highly regulated industry. It affects nutrition and thus health and social well-being in society. It has an equally profound effect on the landscape and the environment.

For these and many other reasons, society imposes various duties and constraints on farmers. Farmers receive payments and compensation for fulfilling these duties and respecting these constraints. Communicating and controlling this whole system is a challenging task for both parties: for public administration (at national and European Union level) as well as each individual farmer.

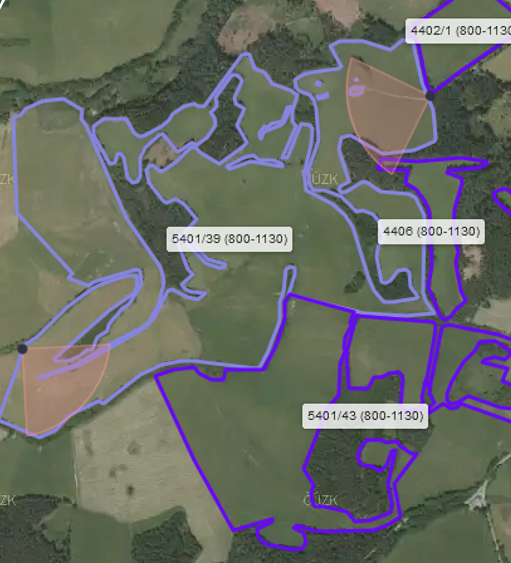

LPIS (Land Parcel Identification System) was created for this communication and control. It is one of the basic elements of the Integrated Administrative Control System (IACS) and is legally anchored in Regulation (EU) No 1306/2013.

In the Czech Republic, LPIS together with the Integrated Agricultural Register (IAR) form the backbone of the Farmer Portal. These systems essentially record online each animal, its life path, each parcel and the cropping practices applied to that parcel. Field manure, grazing, animal sheds, everything is mirrored in the geographic information system.

This year, this already massive system has been expanded to include two additional portals: AMS (Area Monitoring System) and GTFOTO, a photo geotagging app.

These systems are designed to continuously monitor farmers using satellite imagery and inform the state government of farmers’ compliance with all the rules it has set. It goes without saying that the taxpayer has the right to demand value for money from farmers and has the right to monitor the work. However, a system that monitors farmers 24 hours a day, 365 days a year can cause discomfort.

Until now, farmers had been inspected by regular aerial photography at approximately two-yearly intervals, and random on-site physical inspections.

The AMS portal has now introduced a ‘traffic light’ scoreboard. All plots of land farmed are rated by colour – green, orange or red. The system was rolled out this year. In August, a number of farmers saw red scores. The stress in the farming community was phenomenal. Officials at various levels of government had words of apology for us, saying not to worry, wait for the system to settle down. It’s a bit like telling someone they can run a red light and hope for the best.

The satellite evaluates each area based on chlorophyll. When communicating with the farmer and the system still uses the original aerial images. On these images it flags areas that are not clear in terms of chlorophyll. The farmer then has to download an app on their mobile phone. Scan a QR code to pair the app between the computer and the smartphone. And take a picture of the situation at the site that the system has assessed as problematic.

“Download the app on Google play and scan the QR code”

My experience: it took me four days from receiving the email to completing the assigned task. I watched several recommended videos and presentations. I downloaded the app on Google play, generated a QR code on my computer, and showed it to the app so it would know which farmer I was. I could see the task on my computer, but not on my phone.

I spent the whole day trying to figure out what I was doing wrong, why it wasn’t syncing. I gave up and called the office. A very nice, helpful clerk told me that I had not opened another tab and had not enabled the sync. Tab on the left, tabs on the right, enable sync.

With the task on my smartphone, I went in search of the location I was supposed to photograph. A bit like geocaching: the system says you are not at the location, you are closer but not at the location. You’re at the location but at the wrong angle. Finally, I’m at the location and in the right position to take the picture. The photos are uploaded. The next day, as I was bragging about my amazing accomplishment, I realised I had missed the last step. Submitting the task. But you only see that when you scroll down. So it took me four days altogether.

I am describing this whole adventure in such detail not to reveal to the world my utter incompetence with new technologies.

There is a conception that these systems are great and can be very helpful, created by people whose technological prowess and even willingness to use them is quite different from that of the end users.

I am a woman in my early 50s, willing to learn new things. If I look at farmers around me in terms of age and computer literacy, I would say I am about average. Which means that half of us are older than me or less computer literate.

Telling these farmers to “download the app on Google play and scan the QR code” just comes across as obnoxious. People who choose to spend their lives in the countryside with animals do not tend to be fans of computers.

Student farmers can help

It seems to me that the solution is right under our noses. In the Czech Republic there is a massive network of agricultural and veterinary training centres, schools and colleges that are full of students who would find the task that stressed me out for a week a pleasant challenge. My farm alone works with an agricultural trainee, three students from agricultural schools, and an entire agricultural college. I don’t understand why the state doesn’t train the teachers of these schools in these different tasks, and then create a demo for the students, and ask them to give feedback to the system.

For at least seven years now, I have taken every opportunity to raise the topic of a Farmer Portal demo for schools. Preferably a nationwide demo. It would also be a tremendous help to the State Agricultural Intervention Fund, which would gain people to spot minor flaws or help with the settings to make it more user-friendly. Farmers would gain thousands of helpers who could assist them during their studies. Young people, when they go to work on a farm, could be given the task of managing the portal – they should be able to navigate one after years of studying.

Such strong training would help in other issues: eradicating overpopulated voles, helping areas affected by drought or frost, and so on. We would be able to assess in real time whether and how farming is having an impact on these issues. Whether there are more or less voles depending on field size, ploughing or no-till farming, and other factors.

During a debate on this subject with a Minister of Agriculture, I learned that there is no money for this. I looked up in public sources the amount of money that the State Agricultural Intervention Fund budget spends on these portals.

[For 2023, an estimated €22.8 million will have been spent on “Data processing and information and communication technology services” – see item 5168 in this report from the State Agricultural Intervention Fund to the Czech Parliament dated 21 November.

Looking at those figures, no one can convince me that creating a demo is a question of money. On the contrary, I think that a well-organised collaboration with schools would save money, not least in the creation of constantly new features of the systems. Not to mention how much it would save when students from agricultural and veterinary schools collaborate with farmers.

Incidentally, on the subject of vole overpopulation: on the Farmer Portal, the public administration has information on the cultivation of every metre of agricultural land. Farmers have asked for the possibility of increased use of vole control products. I suggested that they apply for specific areas through the portal. At that point we would know online if there was a relationship between the size, slope, tillage method, crop and other characteristics of the area and its exposure to rodent overpopulation. The proposal was rejected and the public was mired in debate as to whether or not any of the characteristics had an effect.

The Farmer Portal, the AMS portal and the GTFOTO app are all wonderful tools that, if used properly, can facilitate the work of public administration and perhaps even improve communication between farmers and the public, whether from the perspective of taxpayers or buyers. Schools need to be given the opportunity to teach their students how to use these systems and to evaluate the information that they provide to us as a society.

More on Digital

EU Digital Agriculture Needs Clear Socio-Ecological Directions

Strengthening Multifunctional Agriculture through Digitalisation: Insights from Europe and Japan

Rural Japan | Agroecology, Diversification and Digitalisation on Hashimoto Family Farm

Rural Japan | Diversification and Digitalisation on a Dairy Family Farm

The Influence of EU Policies in National Rural Digitalisation

Italy | Digitalisation, Short Food Chain and Sovereignty – Fuori di Zucca

A Rural Proofed CAP post 2020? – Analysis of the European Parliament’s Position

Rural Dialogues | The Three Conditions of Sustainable Rural Digitalisation

More on Czech Republic

Czech Republic | COPA No Longer Defends Interests of Majority of Czech Farmers

Letter From The Farm | Freedom, Forgotten Places And The Future Of Farming

Letter From The Farm | Half The Price Of Your Food Is Paid By The EU