By Guy Pe’er & Sebastian Lakner

By Guy Pe’er & Sebastian Lakner

Toilet paper was at a premium, wine was scarce, but the Covid-19 crisis was not a threat to food security. Meanwhile a more insidious threat persists beyond the pandemic, as CAP payments – intended to buy food security for the EU – continue to sponsor the destruction of the environment in which our food grows. It’s time to dump the food security narrative, argue Guy Pe’er and Sebastian Lakner.

One common claim in the current public debate around European farming and the CAP post 2020, is that in light of global food security risk we cannot allow ourselves to take land away from production, that is, in favour of environmental protection. In the context of the COVID-19 crisis, we are also hearing that the crisis demonstrated the centrality of food security. In the following post, we provide a number of arguments demonstrating lack of evidence to support these claims – and propose that the food security narrative should best be aborted.

A: Food security itself is not a major challenge in the EU

1. Generally, food security is not a major issue in the EU.

The EU is self-sufficient, i.e. producing beyond the own demand (See table 1 below). This leads to net-exports, especially in the meat sector. On the other hand, meat production in the EU is relying on the imports of feedstuff from other continents, such as soy from Latin America. Notably, the later might be problematic from a food security perspective, but for other reasons.

2. Poverty in terms of food-access expresses itself in different forms in Europe.

Evidence suggests that within industrial countries we can identify other challenges in our food systems:

a) Food-waste – a report of Thuenen-Institute for Rural Studies estimates that about 12 mio. tons of food per year, of which 7 to 7,6 Mio. tons could potentially be avoided. About 52% of this amount comes from private households (see Schmidt et al. 2015: 59/60). It is noteworthy, that some of the food waste (like residues from harvests) might be hard to avoid, simply because economic incentives are missing (Koester 2013), but both of these figures suggest other challenges but food security per se.

b) Overconsumption and obesity: A report states that “the prevalence of obesity, however, has risen substantially, especially among men: in GNHIES98, 18.9% of men and 22.5% of women were obese, in DEGS1, these figures were 23.3% and 23.9%, respectively.”. The study also points at an increasing rate of obesity among young people. (Mensink et al. 2013). Practically, unhealthy diets in the EU are driven more of by obesity and overconsumption, as well as lack of awareness, rather than access to (healthy) food.

c) Health related issues resulting from this. Demonstrated diseases include diabetes, cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), dementia and cancer. In OECD-countries, about 311 bn. US$ (PPP) are spent to treat diseases caused by overweight. This is about 8.4% of all health spending in these countries (see study of Vulik et al. 2019: p75).

In public surveys among EU-citizens and consultations, real poverty or issues of food security do not appear as a top priority (EU Commission, Eurobarometer 473, see figure 4 at the bottom). Risk of starvation or food security is not among the main challenges of Europe’s food-systems. When it comes to food, too low economic and social participation is the main challenge. We can provide enough food, if there is enough purchasing power.

3. There is no indication of food insecurity due to Covid-19.

The Covid-19 pandemic, as much as it was sold to claim that demonstrated how important food security is, de facto showed the opposite. For example, in Germany shortages were seen in toilet paper (see The Local), and in France, wine was scarce. However, food supplies were secure, the problems of the shutdown were found in other details of the agricultural and food supply chains. Security was not the issue.

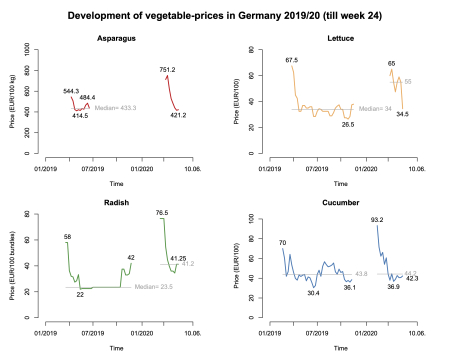

In agriculture, we were lacking the support of seasonal workers in fruit and vegetable production, which astonishingly could be found locally in some cases. For Germany, travel stop prohibited arrival of labour-forces from outside Germany. But surprisingly, calls for volunteers in Germany via online-platforms were often not responded. On April 2, the German Ministry for Food and Agriculture (BMEL) announced a set of rules to allow 40,000 seasonal workers to travel by plane to Germany in April and May (see Blogpost at Arc2020) leading not only to falling prices for vegetables but also to a debate on the social misery of seasonal workers, non-compliance to Covid-19-safety-rules (Panorama of 23.04.), reported cases of misuse of labor contracts, and large-scale outbreaks of Covid-19 (Tagesschau am 9.5.2020, Spiegel 18.05., Spiegel 15.04., taz 16.04.). Notably, the German prices for vegetables so far do not suggest a large-scale scarcity of vegetable production (figure 1), especially after opening up the borders in April.

This example points at a completely different direction than food security, namely, an inefficient use of existing labor forces. In light of rural depopulation, this reaffirms the centrality of rural employment challenges (and hence, the importance of CAP’s Pillar 2).

4. The Covid-19 pandemic demonstrated the importance of a good system of international trade.

After some difficulties in March 2020, followed by generating regulations for safe imports, it is evident that EU intra-trade is largely functioning, if the supply chains are well organised. Main threats come from unsustainable food-systems like in the slaughtering industry or some of the asparagus farms, where basic labour-standards were not kept. Thus, if anything, the Covid-19 pandemic revealed the importance of safe food standards of employed farm- and food-workers and sustainable working relations, whereas farm production was largely unaffected. And the Covid-19-Crisis including the shutdown rather revealed, that open borders and a functioning agricultural trade were key for food security. Rather than the CAP or Direct Payments.

5. Where are the largest potential to contribute to global food security?

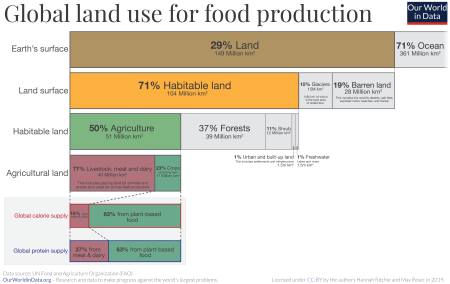

If food security is indeed an issue, and Europe, as often claimed, should somehow contribute to addressing it, then why not produce food? Much of the EU’s UAA is used to produce feedstuff and biofuels. For example in Germany (see figure 5, at the bottom), about 57% of the land is used to produce fodder, another 12.1 for bioenergy and 1.8 for industrial use (see Destatis 2019). Even if coupled production is not included in this calculation, a majority of the area is taken off from effective production, whereas non-production areas such as fallow land cover a marginal area (1,9%). On a global scale, the picture is similar (figure 2):

Worldwide, we use about 77% of the land for animal production (see figure), accounting for 65% of all land use changes from 1994-2011 (Alexander et al. 2016), and 4% of crop land for the production of biofuels (UFOP 2018 Global Report). If it is food that we are lacking, these should be the first to be taken. Another option could be to reduce meat exports and use the respective land to produce crops. In other words, if we take food security seriously, highest priority should be given to reducing our ecological footprint by reducing both intensive animal production (Schader et al. 2015) and our consumption of animal products (meat, dairy). This would require changes in our food and energy policies, hopefully to come (at least partially) through the Farm to Fork strategy.

B: CAP is not the solution

6. Food security was a historical, initial motivation of CAP.

While food security was the main motivation to create the CAP in a post-WWII Europe, it is clearly not a relevant objective nowadays. From a continent with substantial starvation and hunger and a dependence from US food deliveries, the EU developed into a self-sufficient and even over-producing continent. For instance, the self-sufficiency rate of grain increased from 94% in 1968 (EU-6) to 120% in 1989 (EU-12). In consequence, historical CAP reforms placed central efforts to intentionally move away from coupled (=production-oriented) support, following justified concern that this kind of support leads to overproduction, distort global markets and drive environmental degradation.

7. The current role of CAP payments focuses on farmers, not on production:

While concerns are repeatedly raised as if retaining the CAP’s Direct Payments is essential for food security reasons, our Fitness check review (Pe’er et al. 2017) indicated the opposite: Direct Payments actually act to reduce rather than increase productivity because they secure farmer income regardless of farm management. So, if at all, Direct Payments are influencing farmers decisions towards a less efficient production. So, if food security is a problem, DP is not the solution!

From a global food security perspective, a strict market orientation (including strong and uniform environmental enforcement) might a more suitable strategy than paying production distorting coupled payments, which harm the environment and lead to a mismatch of production and supply even beyond the EU internal market. Areas where farmers struggle economically, and end up abandoning, may indeed warrant more attention but this should be addressed through the relevant instruments in Pillar 2.

C: Diverting from the right discussion

8. Food Challenges should be solved globally, from farm to fork

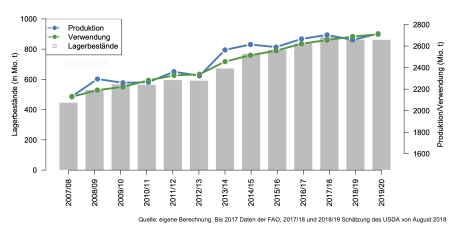

Many countries out of the EU, i.e. without the CAP, are producing just enough if not too much. According the UN Food and Agricultural The global food balance has been positive in most of the last years (see figure 2).

Figure 3: World Cereal Production, Utilization and Stocks (Data from FAO 2020)

Due to increasing world population, the demand for food indeed is expected to rise. But about 50% of the food consumed globally is produced on small-scale, smallholder farms, including a substantial contribution of subsistence farming. For instance, wheat production from countries with yields above 6 t/ha and year (North America and Europe) represent 12.5% of the world harvest. The same share come from countries with a yield potential less than 2t/ha (Tittonell et al. 2016). Any slight increase of the yields in these countries has a larger effect than any debate on production versus non-production areas (such as Ecological Focus Areas) in the EU.

Any strategy to cope with food insecurity has to include a proper development strategy for small-scale family and subsistence farms in developing countries, not only for reasons of resilience, where in such a case different regions and farm types contribute to global food security. Moreover, with current production exceeding global needs, the real challenge relates to food distribution and inequity in access to resources. Here, the EU does have a role in reducing its global impacts, primarily due to land-use changes driven by our consumption.

9. Food security is a wrong argument to secure CAP-payments

A production-oriented discussion is not helping the majority of farmers, i.e. those managing small farms. In order to produce more, one can intensify management using, e.g. machinery or more chemical inputs. Here, we find ourselves in the centre of the “technological treadmill theory”, which describes the mechanisms leading to a larger uptake of technology on the farms, replacing labour forces, which however leads to an increased overall structural change.

If the main objective of the CAP-payments is to secure on farm labour and support family farming, any sharp increased food security can appear as counter-productive, especially, if we recognize that a certain pressure for taking up technologies is there anyway. The narrative of food security (implicitly driving productivity) is contradictory to the narrative of supporting and protecting family farming, which is still the main objective of Direct Payment.

Better arguments for payments are public goods or a solid, facts-based welfare policy for the farming sector – where we, however, strongly doubt that the latter is going to happen. So the public goods argument deems the most reliable to maintain support for the farming sector, with all challenges included.

10. Secure food production needs functioning agro-ecosystems

Finally, especially when placed in the context of the Common Agricultural Policy and attempts to strengthen environmental protection, shifting the discussion toward a production versus nature-conservation creates a polarized debate that is not only evidence-free but also harming the reputation of farmers. Notably, the Public Consultation of 2017 indicated that 94% of non-farmers and 64% of farmers think the CAP should do more to protect the environment. This indicates that most farmers do care for the environment but want to be supported, and incentivised, in doing so. Thus, placing the farmers against the environment secludes farmers from the rest of society, portrays them in a negative way, and does a disservice in failing to represent farmers’ own opinions and perception as keepers of the environment. Given that 40% of the EU’s budget is allocated to supporting the farmers – as a sector – such a line of argumentation may further erode the support of the public for the CAP.

To sum up, whenever food security and production are brought as counterarguments to environmental protection, or as justifications to keep the CAP as it is, one should question the evidence and the argument. As long as the CAP fails on both farmers and the environment, there is a win-win to explore, for the benefit of the EU as a project.

Final remarks: A better narrative for the CAP

The main argument to address ecological challenges in the EU, and to set aside some non-production areas, is that nature provides invaluable insurance value for farming systems, for production and for our society.

We need biodiversity (pollinators, pest controllers) for most of our food types, we need trees and bushes to retain soils and water and to combat climate change, and we need functioning ecosystems for long term production. The low harvests due to drought in the summer 2018 have highlighted the necessity to incorporate risk into planning. Farms with wide crop-rotations and high CO2-content had better harvests, since soils could keep humidity and plants could still grow.

We need landscape structures to block wind and water erosion: In spring 2011, a large-scale car accident near Rostock occurred due to strong sandstorm (Spiegel 08.04.2011). Terraces, hedges and trees can impede such risks.

So indeed, the stats may seem simple: a reduction of production for non-production may seem like hampering incomes, but in reality, much more is at stake if we lose soil fertility or pollination, or let our fields bake exposed in the sun of prolonging summers. Food security cannot be achieved in a rapidly changing world without a proper ecological strategy, including environmental education, to retain and improve the knowledge which many farmers already have, and others are rapidly forgetting: We cannot survive without the services delivered by functioning ecosystems.

This article was originally published with references on Sebastian Lakner’s blog. Comments and Questions are welcomed.

More on food security

Effects of Coronavirus on Agricultural Production – a First Approximation

Effects of Coronavirus on Agricultural Production – a First Approximation (part 2)

Coping with Covid19 – Supply Chains and the Butterfly Effect

Framing Farming – Nationalism, Food Security and Food Sovereignty

UK | Coronavirus: Rationing Based on Health, Equity and Decency now Needed

UK | Coronavirus Diary: the Virus That Did a No-Deal Brexit on our Food Supply

Coping with Covid19 – Commoning as a Pandemic Survival Strategy

Council of Ag Ministers meet on Covid19 | Green Lines, State Aid, CAP Extension

Coping with Covid19 – Tensions in Farming, Trade and the EU Institutions

Coping with Covid19 – the Open Food Network and the New Digital Order(s)