What’s next for our countrysides? Before we even begin to consider re-scaling the rural, we must slow down and work in deep collaboration and coproduction – with all. This requires deep listening to the voices on the ground. But also trusting farmers and artists, who are skilled at working alongside and within communities, human and nonhuman. Otherwise we will continue to do the countryside a disservice, argues Kate Genever.

An artist and farmer, Kate, together with her two sisters and parents, runs the Three Daughters Croft Farm in Uffington, Lincolnshire, UK, where she specialises in lambing. For Kate, making art feels much like farming.

These words were composed en route from her farm to rural Denmark, where Kate presented at the Re-Scaling The Rural conference.

Yes I am Kate Genever……. I am an artist and farmer and this presentation, like both these jobs has no final answers, but does take a position. Arguing that, like my beautiful journey here, all the way by train – oh and this morning’s bus – from east England, we must slow down, respect, recognise our impact, pay attention, risk, work in deep collaboration and coproduction – with all – before we even begin to consider what’s next for our countrysides.

I am aim to help us consider re-scaling and how creativity can excel under strain and how this leads to forms of courage that makes champions of the overlooked.

As a farmer I work alongside the family on our traditional mixed farm in South Lincolnshire, England. I’m entwinned in the daily care of animals and land. For those who don’t know this area, it’s low lying (at the max 20m above sea level), being the highest ground before the vast reclaimed highly productive area called the Fens. Drained by the Dutch from about 1400 onwards it’s the Breadbasket and veg box of the UK.

Improvisations

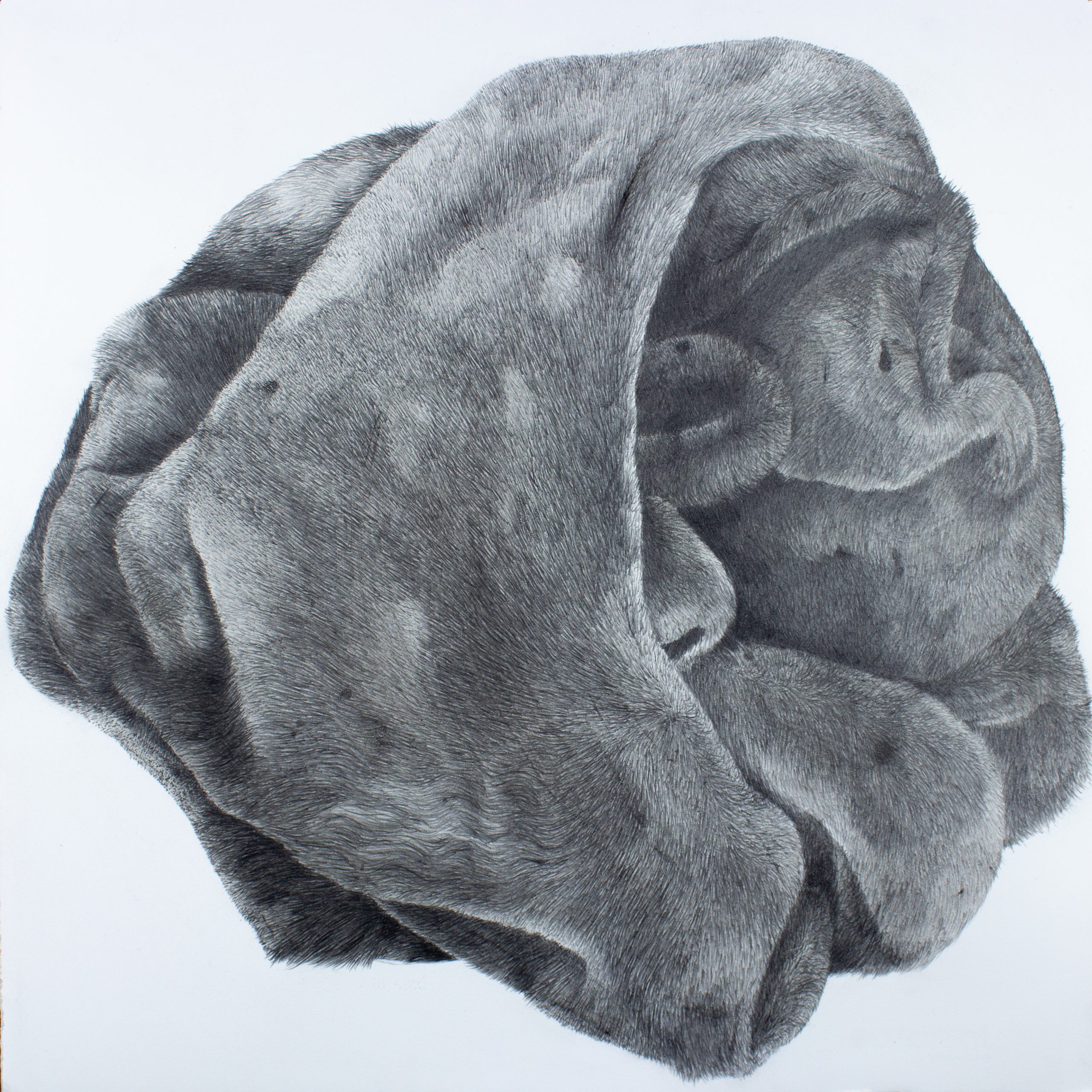

Importantly as artist and farmer both affect each other in action. Which perhaps explains why I make sense of the world through drawing. I take drawing to be more than a technique or process, rather a disposition revealing our connections with a world of materials and each other. I draw from, with and together, in places, over extended periods to consider how we improvise, imagine, and cope, in response to our immediate problems. I support people and communities to reflect on and activate change.

Many describe what I do as a social practice. I call it drawing, it feels much like farming.

I work in marginalised places, over extended periods, be it refuges, secure units, prisons, rural, coastal and urban areas…. I build deep connections with people in the celebration and support of site-specific responses, DIY architectures and resourceful actions – IMPROVISATIONS.

I use process-led principles, and advocate asset-based co-production approaches – often working in collaboration with other artists, organisations, researchers and curators. This work is deeply political and is driven by a determination to reduce the impact of being overlooked or worse still romanticised.

I think Improvisation is responsive, temporal, courageous and comes from really dwelling somewhere. Tim Ingold, the anthropologist, says, the improvisational world is one that is crescent rather than created, in that it is always in the making.

The stuff I like ranges from branches being used to prop open gates to window latches as coat hooks to supremely elegant, poetic clever, sophisticated, buildings, community led programs. The makers are masters of invention, working often with what’s at hand. I am humbled by their attention and lateral thinking. Ordinary subjects which in their ordinariness are extraordinarily representative is a John Berger phrase that sums it up perfectly.

A social practice that feels much like farming

Begun in 2007 during my MA at the Royal College, but still ongoing, Farm Archive contains many sculptures, drawings, paintings, prints, photos, rubbings and collages. All representing the improvised tools and architectures we as a family make and use when working with animals or growing crops.

The archive has its idiosyncratic system or taxonomies – Round things, Long things and Hold in the hand things, for example. The Long things section contains for example drawings of an aluminium javelin converted to shepherds crook, a 15ft bamboo stick otherwise known as the Walnutter and a looped string used for calving.

The collection is ever growing and is currently be accessioned into the Museum of English Rural Life at Reading University. Importantly though, unlike the collections at the MERL, Farm Archive does not hold any original tools, technologies or architectures. They instead remain in use – changing and being adapted as needed.

Commissioned by Metal Peterborough 2021 -22 HOME/LANDS built on research into farming/rural practices in Lincolnshire and Cambridgeshire in a previous commission. In particular how farmers and countryside specialists work in, on and with the land and how we imaginatively transfer, draw up, celebrate, distil and repurpose it for the healing and nourishment of ourselves and others.

These photos made during the research phase include images of Bowman’s Pumpkins. Europe’s largest pumpkin producer, growing in excess of 5 million ‘Halloween units’ a year. The labour force are majority Bulgarian economic migrants who work 12-hour shifts 12 days on. Alongside this I also interviewed people including flower arrangers, roofers, foresters, sheep farmers and an alpaca farming reiki master! I then made new works in response which included social events, facilitated conversations, photography, print and pottery… All the work combined to form a reflection on making, embedded lives and how identities and values form in complex and layered ways.

Hosted in unique rural spaces such as village halls F.E.A.S.T. [Farming. Environment. Agriculture. Sustainability. Tabled] brings people together and encourages debate by linking social, environmental, scientific and cultural thinking in an artful way. Begun in 2018 with Dr Liz Genever, a scientist and agricultural consultant, in response to the lack of understanding across and between sectors, F.E.A.S.T. builds on both our individual specialisms and our roles as farmers.

F.E.A.S.T always incorporates a weekend take-over of a unique community-based venue. A curated exhibition of 2 artists whose work is relevant to the F.E.A.S.T themes and who are local to setting. A collaboration with cooks who help create a dinner of locally sourced food including food waste. Each meal is opened with specific provocations from both the arts and science.

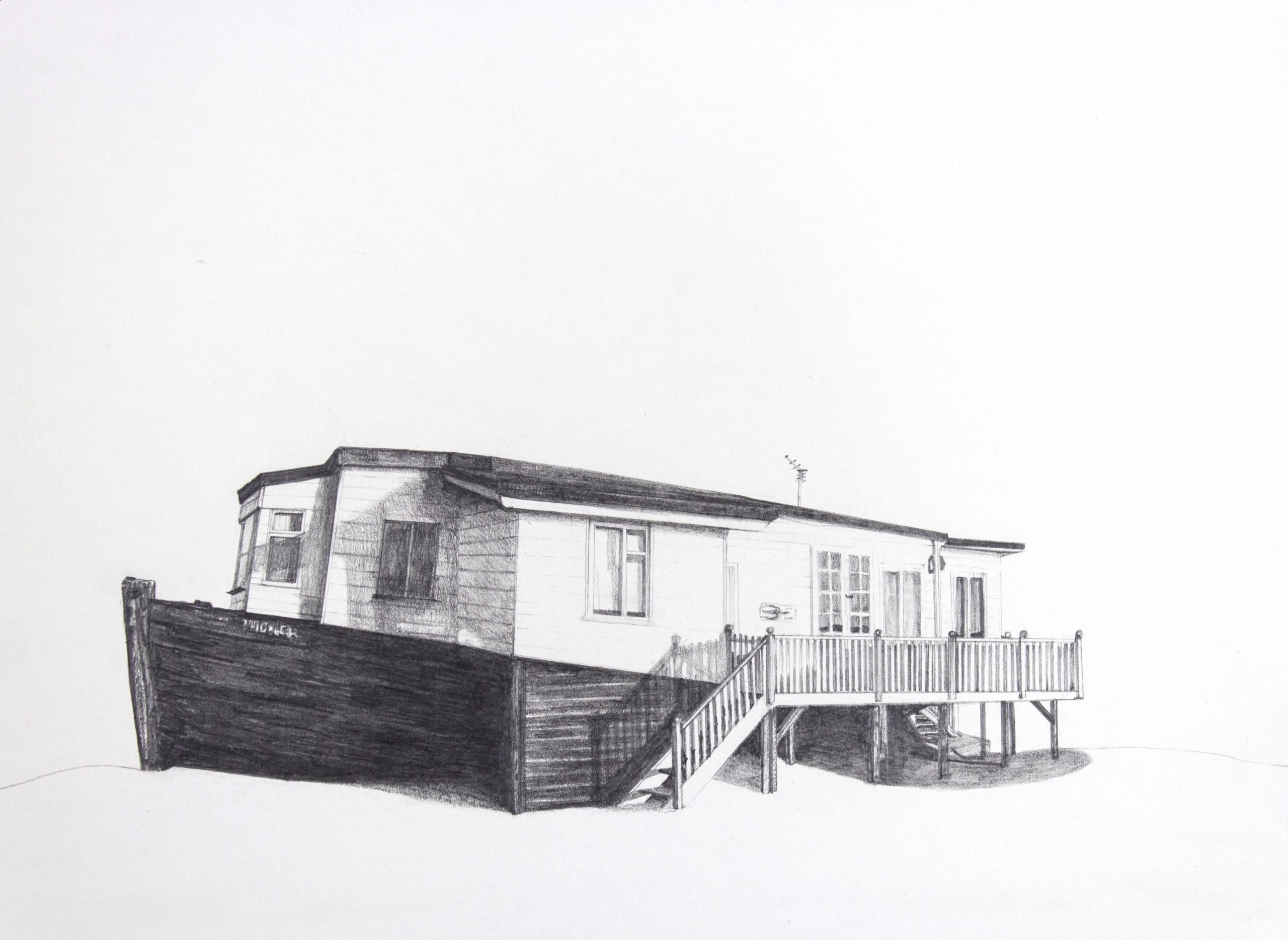

In 2018/2020 with Arts Council England funding I explored communities living in sites I describe as half land half water…Fragile eastern England sites, where residents respond to their immediate stress in clever ways. The works aimed to mirror the disenfranchised residents and reveal to wider audiences glorious tangible and intangible knowledges and tenacity.

For example the becalmed boat/houses in Eulogy to those who lost their lives at sea began as coal barges before being washed up in a flood in 1950 which have since been DIY converted to dwellings using cheap at hand materials. They are constantly being adapted and extended masking the humble boat at each of their centres. Professor Stephen Walker at University of Manchester said: “As well as celebrating improvisation they draw attention to ongoing negotiation and ask us to look the other way, or look another way.”

We all need to see ourselves be loved

But how does all this help us consider Re-Scaling the Rural…. ? What follows is a list series of bullets written using word or idea association. Ultimately it’s a condensed bit of thinking that’s draws on hunches, experience and research. It’s the stuff I think is important about working in marginalised settings.

1. I would argue that 99% of the people I work alongside didn’t go to art school, and therefore didn’t unlike me spend the first two weeks of their degree on a set assignment that meant we were only allowed to use orange crayons, in a white room that had classical music piped in – an attempt via 90s fine art training to perhaps rip off Bauhaus’s Vorkurs foundational approaches to get us to deconstruct and think laterally. Instead the creativity in the communities I work alongside is born of unfettered artfulness, practical need and precarity.

2. Carl Rogers in 1980 wrote about some sprouting potatoes in a bucket in his basement. He said their directional tendency can be trusted. The clue to understanding their behaviour is that they are striving, in the only ways that they perceive as available to them, to move toward growth, toward becoming. To healthy persons, the results may seem bizarre and futile, but they are life’s desperate attempt to become itself.

3. Carl also believed in offering his clients unconditional positive regard – which a baker I know says is another way of showing love. There is no other way to work.

4. All people are working with the light available to them, but I definitely don’t think they should be kept in buckets in the basement. However I do know the most incredible creative solutions and resourcefulness I’ve seen is born out of need and provides elegant solutions that are representative demonstrations of courage, radical-hope and humility. Ways of being that embrace empathy, generosity and acceptance.

5. Budgets that bring curiosity, investigative approaches and people like me to consider a 360 degree view is what’s needed otherwise we risk keeping many people in the dark.

6. Development architect Nabeel Hamdi said in his book Small Change: “Start small and start where it counts.” I like this.

7. However I think he bastardised it from Julia Cameron who in 1992 wrote the book The Artist’s Way and said something very similar…

8. Her book is a guide to unblocking the imagination, it uses free association and love to liberate ourselves from ourselves. So we can create despite fear. Change I know starts in the imagination.

9. She, like Freud, thought we wage a constant war between death instinct and life instinct. And that’s going on out there too.

10. Adam Phillips who recently wrote: “Freedom is available – we may be determined by our biological destiny and our transgenerational histories, but within those constraints are viable freedoms.” But it’s not easy, it takes work and encouragement.

11. I heard Dame Jo da Silva say: “We rush to rebuild, when in fact change in any scenario needs to be people centred and this takes time.” I say it takes more time than you think.

12. I think re-ing things by that I mean re-new, re-generate, re-scale, focuses us on nostalgic better pasts and imagined good futures. This a delusion.

13. Kintsugi on the other hand embraces the act of repair as a creative act rather than an attempt at returning something to a previous state and imagining it not changed.

14. On taking over the broken Glasgow CCA Director Francis McKee said something along the lines of: Now we are conceptually and financially bankrupt the CCA can only now see a new way…. open the doors let the local community in.

15. Uncertainty can be uncomfortable. It’s often tempting to stop pondering and jump to conclusions. But by resisting the temptation to dismiss, solve and despise, it’s possible to open the door to discovering traits that are worthy of sympathy or admiration.

16. Negative capability – which advises we rest in doubt, continue to pay attention and probe in order to understand things more completely – was a concept John Keats the poet described in 1817. I, like him believe, those who are willing to question their own assumptions and adopt new perspectives are in the best position to arrive at new insights.

17. Jonathon Lear’s writing about cultural collapse and Plenty Coup the first nation Crow leader says: “We might see how his response to the challenging circumstances of his time, could be seen as courage. An ability to live well with the risks that inevitably attend human existence…. To be human is necessarily to be a vulnerable risk taker. In such a way radical hope might be not only compatible with courage: in times of radical change, it might function as a necessary constituent.”

18. Radical Hope at its core is like a crying baby reaching out – it doesn’t know what will come but does it anyway.

19. But we are not all loved babies. Some of us live in risky settings.

20. Living in risk excludes us from stable, resilience and makes us unwell. Healthy life enhancing risking is what I’m doing now!

21. Endemic low self-esteem persists in marginalised individuals and geographies – it’s the result of power imbalances and results in us all being afraid of our own greatness.

22. Yet the land and people are full of promise and potential.

23. The rural offers distinct cultural contributions yet these have systematically written out of our national museums and deemed unsophisticated by urban based, urban educated curators, makers, writers and thinkers.

24. The rural needs to be considered and supported like any other marginalised community.

25. This is stuff we all know, but again I reinforce: We all need to see ourselves be loved.

26. In the 90’s Miyomoto Ryuji photographed the artfully made temporary shelters of the homeless in Japan– he said they are not a random collage of recycled parts but rather proves an intentional installation that provide shelter, space, place and a sense of dignity to its disempowered residents. They reveal mankind’s activities since Neolithic times, these hunter gathers show us the very origins…

27. These hunter gathers like those who determinedly build boat houses or tools or trolleys balanced with their life, are all designers often with limited cash and little life security. Their experience of living is central to their ideas and its worth is bound only in feelings towards their creation… I argue it’s an emotional rather than financial investment.

28. Marcel Mauss says in The Gift: One gives away what is in reality a part of one’s nature and substance, while to receive something is to receive a part of someone’s spiritual essence. The thing given then is not inert. It is alive and often strives to bring to its original clan and homeland some equivalent to take its place.

29. The Truth, you see, IS waiting in all things.

Deep listening, and trusting

I’m fighting to bring a consciousness of the rural via a lived experience to as many as possible. There is no manifesto, there is no revolution, rather an energy to speak to power. Which arguably challenges and asks that we scale down before we even think about scaling up. So that distinct creative offers, even in limited light, can be seen and developments don’t look like urban contributions but rather informed radical exciting responses.

Yes I am promoting an approach and offering a warning, which declares without deep listening to the voices on and in the ground or a rooting yourself deep – you will continue to do the rural the disservice it’s sick from.

But don’t just listen – trust farmers and artists too, who, like me, are skilled at working alongside and within communities – human and nonhuman. We are highly productive, bring new ideas and people with us and are relatively cheap, which is good given this work will take a long, perhaps never-ending time.

Precarity and cultural collapse is terrible, but like any trauma, with vision, love, courage and empathy, radical hope and forms of courage can come – producing outcomes that are more than worthy of a glance. Rather they show us new ways to look and versions of dignity that should question all our practices and make champions of those we’ve overlooked.

This is a lightly edited transcript of a talk given by Kate Genever at the Re-Scaling The Rural conference in Denmark in May 2022. Republished with permission from Kate’s blog.

More on rural Europe

The Influence of EU Policies in National Rural Digitalisation

Hungary | Electoral Win for Orbán – can he keep up pro-farmer façade?

Western Balkans | Reviving Rural Areas & Moving Towards EU Integration

A Rural Proofed CAP post 2020? – Analysis of the European Parliament’s Position

Rural Europe Takes Action | For Resilience and Peace – Political Action Now!