By Prof. Dr. Sebastian Lakner (University Rostock)

In March 2021, the German Agriculture Ministers’ Conference and the Federal Ministry for Food and Agriculture agreed on important cornerstones for the country’s CAP Strategic Plan. In his preliminary assessment, Sebastian Lackner shows that while the resolutions have opened the door for a more ambitious CAP in Germany, it remains to be seen whether the federal and state governments will seize this opportunity when they decide on details still to be negotiated. This is an amended version of an article that originally appeared in German on Sebastian Lackner’s blog.

1. Introduction

On Friday March 26th 2021, the German Agriculture Ministers’ Conference and the Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture (BMEL) agreed on important cornerstones for CAP reform and basic features for the financial structure. In the Federal Republic of Germany, agricultural policy is a subject largely decided by the 16 federal states (“Länder”). Especially the programmes of CAP’s second pillar (EAFRD) are designed and implemented at the lower level. Only first pillar decisions, valid for the whole country, are something where the federal ministry in Berlin takes the leading role. But even here, the federal government (“Bund”) and the federal states coordinate the CAP design together – in the German Agriculture Ministers Conference (AMK).

In the following article I present a short, preliminary assessment which essentially builds on my last blog post from March 19, 2021 (in German). In principle, the resolutions are more ambitious than expected from many observers in mid-March, and the financial resolutions may enable the CAP to be better designed with regard to environmental goals. However, important details are still not fixed and the payment levels for individual measures, which can be decisive in terms of efficiency, have not been determined. The legal details and the payment levels will be determined by a working group of the BMEL and the federal states, still with the lead in Berlin. In this respect, the door to a more ambitious CAP is open, but the BMEL and the federal states still have to go through it.

2. Conditionality

The AMK only made a few marginal stipulations on conditionality and the criteria of “good agricultural and ecological conditions (GAEC)”. For GAEC 1 it was determined that an area would retain its grassland status from the reference year 2015. In practical terms, this means that a farm no longer has to automatically plough an area that it uses for fallow land or fodder every five years so that the area retains its arable status. Science had been calling for this regulation for a long time, so this decision is to be assessed positively.

GAEC 9 defines the minimum proportion that a farm must provide for non-productive areas. Here the AMK stipulated that the minimum requirements from the Brussels trilogue are to be adopted 1:1. From a European point of view and with a view to competitiveness, at first glance this uniformity appears desirable. However, in the CAP-reform process the area to which this criterion relates, whether it should be three, five or more percent of the area and what is to be understood as non-productive area are still being discussed. It was demanded that especially fallow land, flower strips and landscape elements should be understood as such areas. However, both the Council and the Parliament have largely watered-down conditionality (see Arc2020-publication on October 29, 2020) and in many details the GAEC 9 are similar to the greening-rules, i.e. allowing catch crops and legumes as “non-productive” areas. However, science has shown, that these options are not effective for the protection of biodiversity (see e.g. our study Pe’er et al. 2017). In that sense, Council and Parliament have largely ignored the recommendations from science. A lot would need to be changed in the CAP-reform text to make GAEC 9 into an effective option. Taking the EU-rules 1:1 accepts the inclusion of a watered-down GAEC 9, so in that sense, the AMK’s proposal is largely unambitious.

The AMK did not take any decisions on other GAEC criteria. The protection of moors and wetlands (GAEC 2) or the protection of Natura 2000 grassland (GAEC 10) can be designed by the BMEL – here it depends on the details and they may or may not lead to effective regulatory principles. So, also in this instance the discussion is not over.

3. Eco-schemes: practices and financial allocations

Eco-scheme measures described in my last blog post from March 19, 2021 have now largely been decided on by the AMK. And, one week after the Conference, the Federal Ministries for Food and Agriculture (BMEL) and for Environment (BMU) figured out some further details on eco-schemes:

- Voluntary increase in the non-productive area according to conditionality (fallow land, flower strips, landscape elements and old grass strips on grassland) (GAEC 9 beyond the obligation of conditionality)

- Planting of flowering areas and strips on arable land and permanent cultivated areas (interline and border greening)

- Diverse Cultures in arable farming, including a minimum proportion of 10% legumes and at least five main crops.

- Support of the maintenance of Agroforestry measures on arable land

- Permanent grassland extensification (for the entire farm)

- Permanent grassland managed for results (4 regional indicator species)

- Arable and permanent crops without chemical-synthetic plant protection

- Management in accordance with the conservation objectives in Nature 2000 areas

Source: see press-release by BMEL from April 13, 2021

These measures are generally effective measures addressing a number of environmental purposes, but the details that still need to be worked out are important. Furthermore, a lot depends on the coordination with the agri-environmental and climate measures (AECM) in the 2nd pillar. And the premiums for these measures can decide whether farmers choose a sensible implementation (for example through an intelligent combination of eco-schemes and AECM), or whether due to high deadweight effects and with low participation in AECMs, low efficiency and effectiveness is achieved.

Regarding the financial allocations, the trilogue negotiations in Brussels have not yet determined whether the budget for eco-schemes should be at least 20% (Council’s position) or 30% (EP’s position) of direct payments. However, AMK and BMEL agreed on 25% of the direct payments for eco-schemes. While this might reflect the most likely outcome of the trilogue negotiations in Brussels (i.e. 25%), it indicates that the BMEL is counting on a less ambitious target compared to the 30% proposed by the European Parliament.

The AMK has agreed on a two-year transition period, which may mean that a little less will be spent on eco-schemes in 2023 and 2024. The AMK has also agreed that, under certain circumstances, spending for AECM in the 2nd pillar will be offset against these spending obligations for eco-schemes. This appears, for technical reasons, even sensible.

4. Eco-schemes: main principles

Overall, the question arises as to how much scientific proposals have been taken into account in the design of the post-2020 CAP, and to what extent the proposals for the content of the eco-schemes can possibly be improved. From October to December 2020, interdisciplinary workshops took place in 13 EU member states, attended by more than 300 scientists from different disciplines (mainly from agroecology, environmental sciences, agro-economics and agro-policy).

At the workshops it was discussed how green architecture can be designed in a favourable way from a biodiversity perspective. Four questions were addressed:

- The overall design of the green architecture

- The design of the eco-schemes (design and implementation)

- Goal setting and monitoring

- Indicators for the CAP 2021-2027

The first preliminary report was published on iDiv on March 10th (Pe’er, Birkenstock, Lakner & Röder 2021). The workshops came very roughly to the following key principles for success:

- Landscape elements and near-natural areas (including grassland) are central

- Diversity and multifunctionality should be a primary goal

- Spatial planning in terms of objectives and implementation

- The “no backsliding principle”, i.e. no decline in environmental ambition in the current funding period.

- Demand a clear intervention logic from the MS

- High Nature Value Farmlands (HNVFs) should be integrated into conditionality, eco-schemes and AUKM.

- Extensively used grassland serves both biodiversity and the climate.

Source: Pe’er, Birkenstock, Lakner & Röder 2021

If one looks at the substantive resolutions of the AMK, it becomes apparent that the first point in particular is complied with in some places. But here it depends on GAEC 9, so that landscape elements and fallow land actually dominate. Spatial planning has scarcely played a role so far. The no-backsliding principle must be examined after the final decisions. There are also no indications for evaluating a clear intervention logic. And the extent to which High Nature Value (HNV) farmland and extensively used grassland are well-promoted depends on the specific measures and premiums, so this cannot be assessed either. At the same time, the recommendations of the scientists can still be considered during programming.

5. Transfers to Pillar II

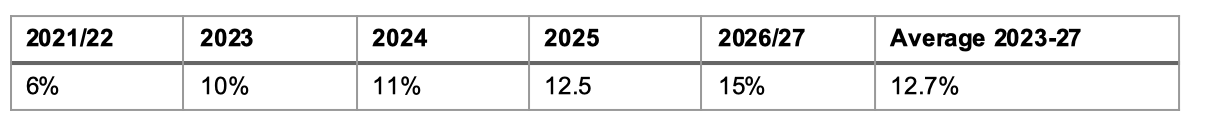

When reallocating budget from Pillar I to Pillar II, the AMK actually agreed on significantly higher percentages. The financial structure of the CAP after 2020, and especially the slightly lower funds for the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD), actually make this necessary (see blog-post of March 19, 2021), and the AMK has apparently drawn the right conclusions from this. The reallocation begins in 2023 with 10% and increases over several steps to 15% in 2026. Between 2023 and 2027 an average of 12.7% of the direct payments are reallocated to the 2nd pillar and are available there for a number of measures:

The reallocated funds come without co-financing and the AMK specifies various possible purposes for the reallocated funds in the second pillar:

- Sustainable agriculture, especially agri-environmental and climate action

- Strengthening of animal welfare and animal welfare

- Measures to protect water resources

- Promotion of organic farming

- Compensatory allowances in nature-disadvantaged areas

Source: AMK resolutions of March 26, 2021

The emphasis on animal welfare is new in this list, otherwise this earmarking was already applied in the last funding period 2014-2020. Most of the tasks are effective and important from an environmental point of view and can be used to design targeted measures for biodiversity, climate measures or the expansion of organic farming. Only the payments for areas of natural constraints (ANC) should be evaluated critically, as these payments are usually not linked to any environmental obligations. The ANC-payments could be linked to a minimum environmental requirement, but so far these payments have not had any causal environmental effects.

Overall, the question arises as to how the reallocated funds are used within the 2nd pillar. If a large proportion is used for animal welfare or the ANC-payments, the funds thus gained are likely to be spent quickly. In this respect, the reallocation opens up possibilities, but here again it depends on the specific measures. The measures will be determined within the rural development programs (RDP), which will only be programmed by the state ministries during the year, and submitted to the EU commission for notification. Therefore, here again, the decisions open up opportunities, however, many details are still to be determined.

6. Coupled payments for grazing premium

A coupled payment is introduced for suckler cows (EUR 60 / ha) and for sheep (EUR 30 / ha). In the last funding period 2014-20, Germany did not use coupled support (as the only MS in the EU), so the decision opens up a new instrument. In principle, these payments could make sense from an environmental point of view, as suckler cows and sheep often graze on biodiversity-rich grassland.

The economic accounts in Germany clearly show that this type of husbandry is economically difficult: The type of farm keeping sheep and suckler cows is called “other grassland farms”. This type of farm achieved a lower profit than all other types of farms in 2017/18 with an average of € 41,447 per company and only € 30,057 per labour unit (see BMEL 2019 Agrarbericht 2019: 77, see also table below). It remains to be seen whether this premium is actually linked to environmental criteria. The AMK has also stipulated that this premium is only available for pure suckler cow farms that do not keep dairy cows at the same time. This seems to make sense in terms of structural policy, but it could finally drive the process of the division of operations (if it has not already ended).

7. Redistribution: the first hectare

The AMK and BMEL decided not to apply any capping or degressivity. Instead, Germany will continue the practice to pay increased payments for a number of x hectares (first hectare-payments). In the next funding period, 12% of the direct payments will be used. For the first 40 hectares, the payment will be 69 €/ha and for the following hectares 41-60, 41 €/ha will be paid. This is substantially higher than in the last funding period 2014-2020, where only 6.9% of direct payments was paid for the first 46 hectares. The financial volume increased from 6.9 to 12%, however, the higher limit of 60 hectares is just a result of structural change.

All three redistribution measures are criticised from a structural policy point of view. Small farms are neither particularly environmentally friendly, nor has it been proven whether small farms are socially disadvantaged per se. (Note, that this finding is only valid for the EU context and it refers to farm-size, not to smaller field size, where we can definitely observe positive environmental effects.) The size by hectare says little about the economic performance of a farm. The following table shows the profits and the possible redistribution effects of the most important types of agricultural operations in Germany in the 2017/18 financial year:

If the figures above are used to derive the premiums, the average base premium for the years 2023-2027 is € 152.54/ha and a first-hectare payment of € 31.02/ha. The present calculation is a rough estimate and is therefore based on a simplified basic premium of 150 € / ha and payments for the first hectares of 30 € / ha. If calculated both together, we receive the direct payment (w/o first hectares) as a reference to compare with. If, on the other hand, the first 60 ha are given a premium of € 30 / ha, a redistribution effect becomes apparent.

We can observe different redistribution effects between different types of farms. The pig and poultry farms, on average smaller in terms of area but economically quite powerful, achieved higher profits per labour unit with a profit of 39,780 EUR/ labour unit. The lowest profits can be for “other grassland farms” (sheep, suckler cows) and mixed farms, achieving only 30,000 and 30,600 EUR/LU. Applying the first hectare payments, arable farms, other grassland farms (sheep, suckler cows) and the mixed farms are losing. Especially the latter two achieve lower profits, which suggests that this redistribution does not fit to the economic competitiveness.

The calculation is a rough average view over all German farms (disregarding regional difference), it only shows the redistribution effects as an approximation. But the main principle of this measure is captured: Farms with a large area (farms in East Germany, other grassland farms) lose out compared to farms with lower land endowment (= pig and poultry farms and smaller arable, mixed and dairy farms in Southern Germany). Smaller farms in southern Germany win overall, containing in many cases also part-time farms, which do not rely to the same extent on income-payments. The first hectare payments with its redistributive effects cannot be reconciled with performance. Size in hectares does not give a reliable indication of economic viability and the distribution does not become fairer by applying first hectare payments.

Another redistributive effect is taking place between eastern and western Germany. Farms in eastern Germany, larger farms on the one hand benefit from economies of scale. However, it seems a bit daring to provide 12% of the first pillar for the first hectares to compensate for economies of scale.

On the other hand, large farms in rural regions in eastern Germany are often the only employers in villages, so any cuts on these farms may also endanger scarce employment opportunities. For small farms, however, the payments for the first hectare are hardly enough to improve their own situation on the lease market. In this respect, although this payment has a structure-preserving effect, it does not open up any long-term prospects for small farms (see the modelling by Balmann and Sahrbacher 2014).

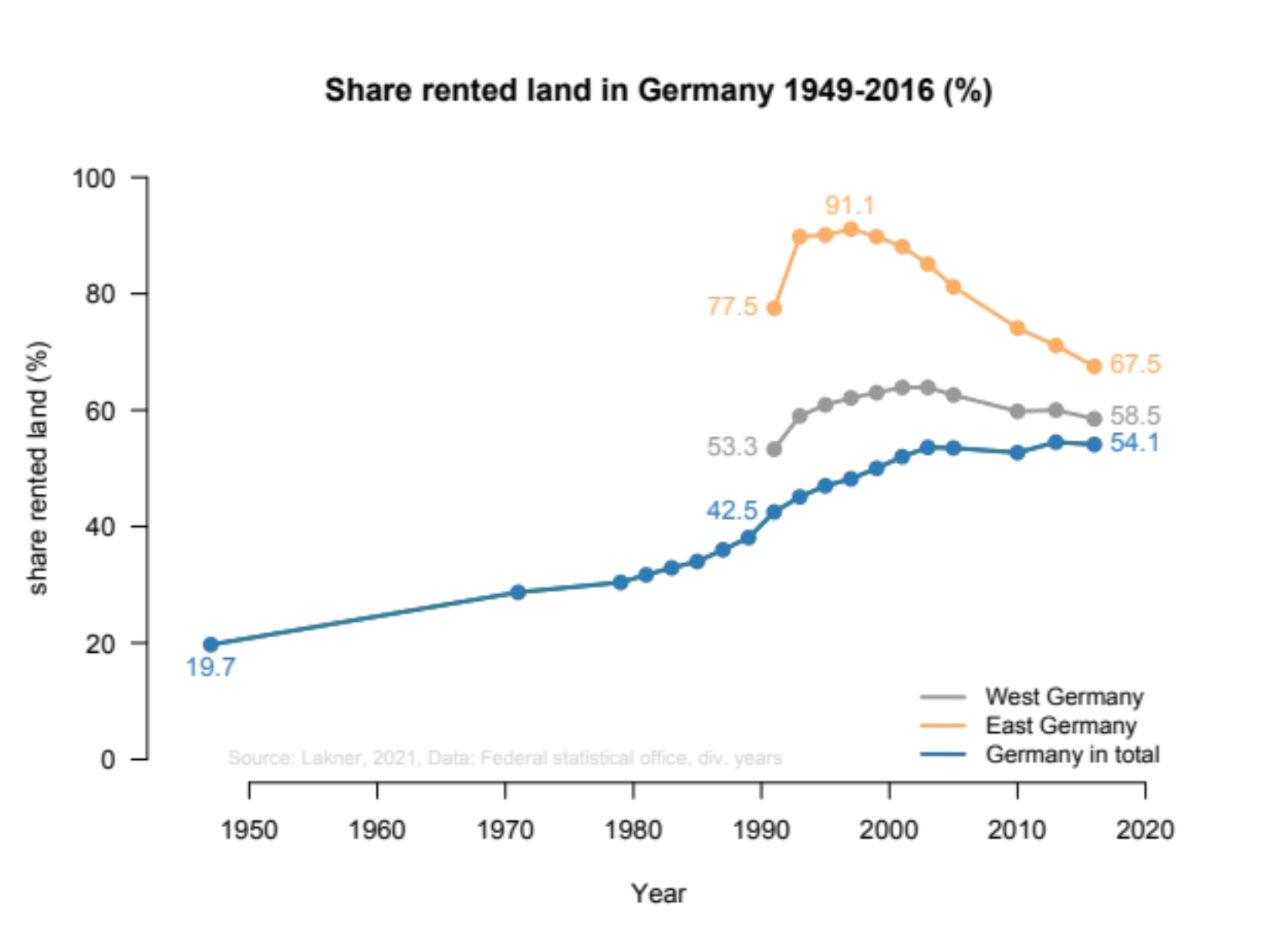

Farms in eastern Germany often have a lower share of ownership: On average, the lease share in the east is 67.5%, in the west it is only 54.1% (Figure).

Because direct payments are at least partially passed on to landowners via the lease agreements, farms in the east benefit less from the direct payments and at the same time lose more from the first hectares. For this redistribution, too, there is no clear formulation of objectives on the part of agricultural policy and one could come to completely different conclusions in terms of distributive policies.

It is particularly dubious that large suckler cow and sheep farms are disadvantaged by the redistribution. These farms, which are important for nature conservation, lose with the first hectares and are compensated in the next step by the coupled premium. Presumably, the animal premium (depending on the design and upper limit) is usually higher, but this shows which manoeuvres are necessary to compensate for the incorrect control of the first hectares. This redistributive policy is not oriented towards individual or group-specific needs and this regularly leads to incorrect management. No matter how we observe the case, we often come to the same conclusion, that direct payments are not a useful or targeted instrument for equalising income-differences.

Overall, the few, rather rough considerations show that the redistribution measures actually do not lead to any substantial improvement in direct payments. The economic need of a farm does not necessarily correlate with the size by hectare but depends on individual circumstances. Overall, it makes much more sense to implement income policies at household level, but so far there have been no considerations in this direction and there is hardly any data from agricultural households that would provide an indication for the design of such a policy. In this respect one always comes to the same conclusion: 1) justify goals sensibly and substantiate them with figures and 2) abolish direct payments or transfer them to a more sensible instrument of income support.

However, the decisions of the AMK on income policy (unlike environmental policy) are not suitable for correcting the deficits of previous policy. And all of the state ministers and agricultural politicians of all parties have not yet had a convincing answer to this issue. The only positive aspect in this implementation is that the share of basic payments and first hectares is shrinking over the financial period, and probably, this is the best evaluation we can give here.

8. Financial decisions

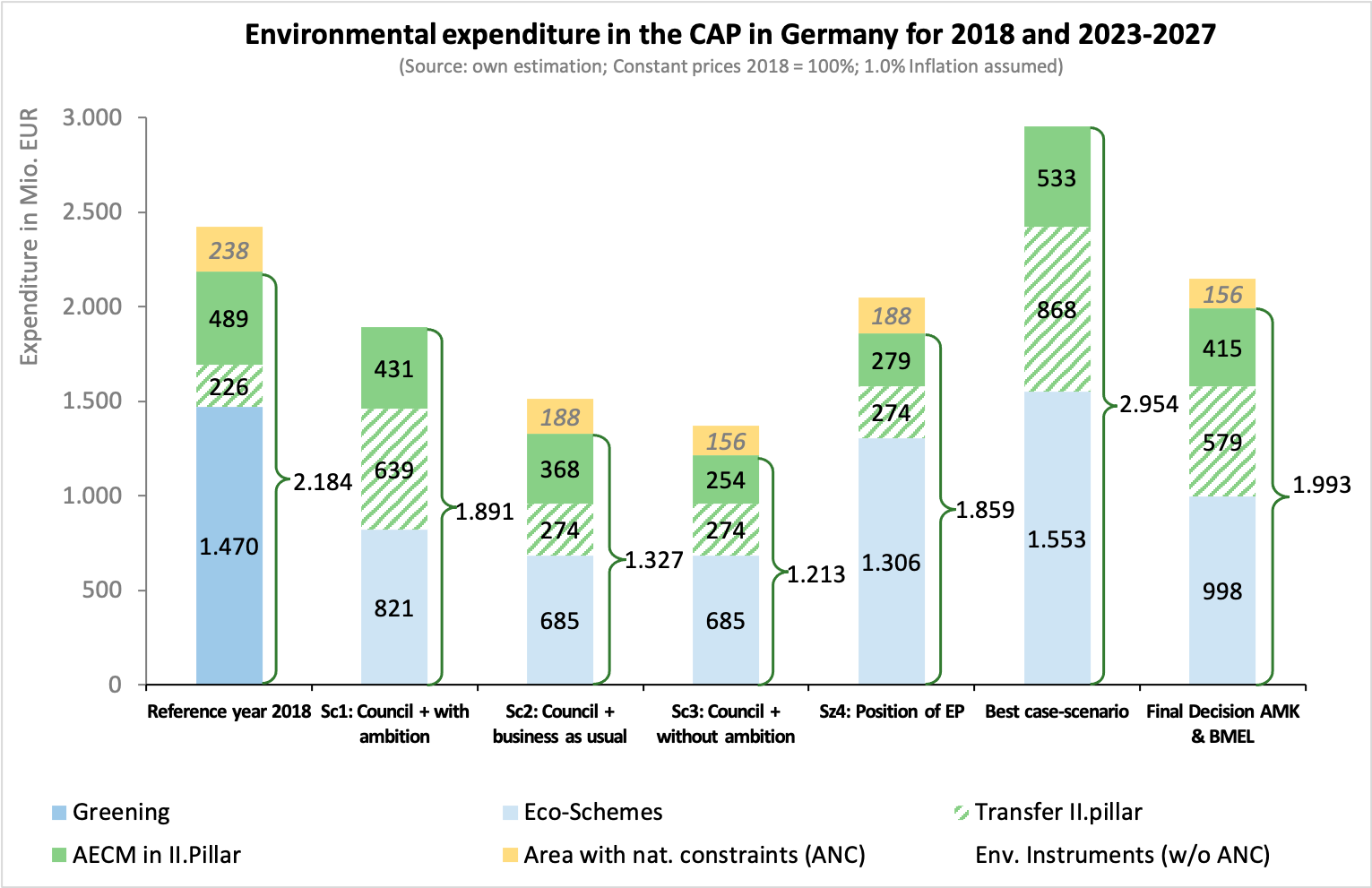

It appears that in the best-case scenario, financial resources for environmental measures will be provided in the years 2023-27 to a similar extent as in 2018. Taking my evaluation for Greenpeace in January 2021 or my last blog in mid-March 2021 (both in German), it didn’t look like that for a long time either. Assuming that the shifted funds will be made available for agri-environmental measures and that the federal states programme measures accordingly, almost EUR 2.14 billion will be available annually for environmental measures in the CAP. However, the AMK & BMEL resolution states that the funds that are shifted to Pillar II will also be used for animal welfare and payments for disadvantaged areas. If one carefully assumes that at least 10% of Pillar II is used for payments for less-favoured areas from these funds, then there are 2.0 billion euros.

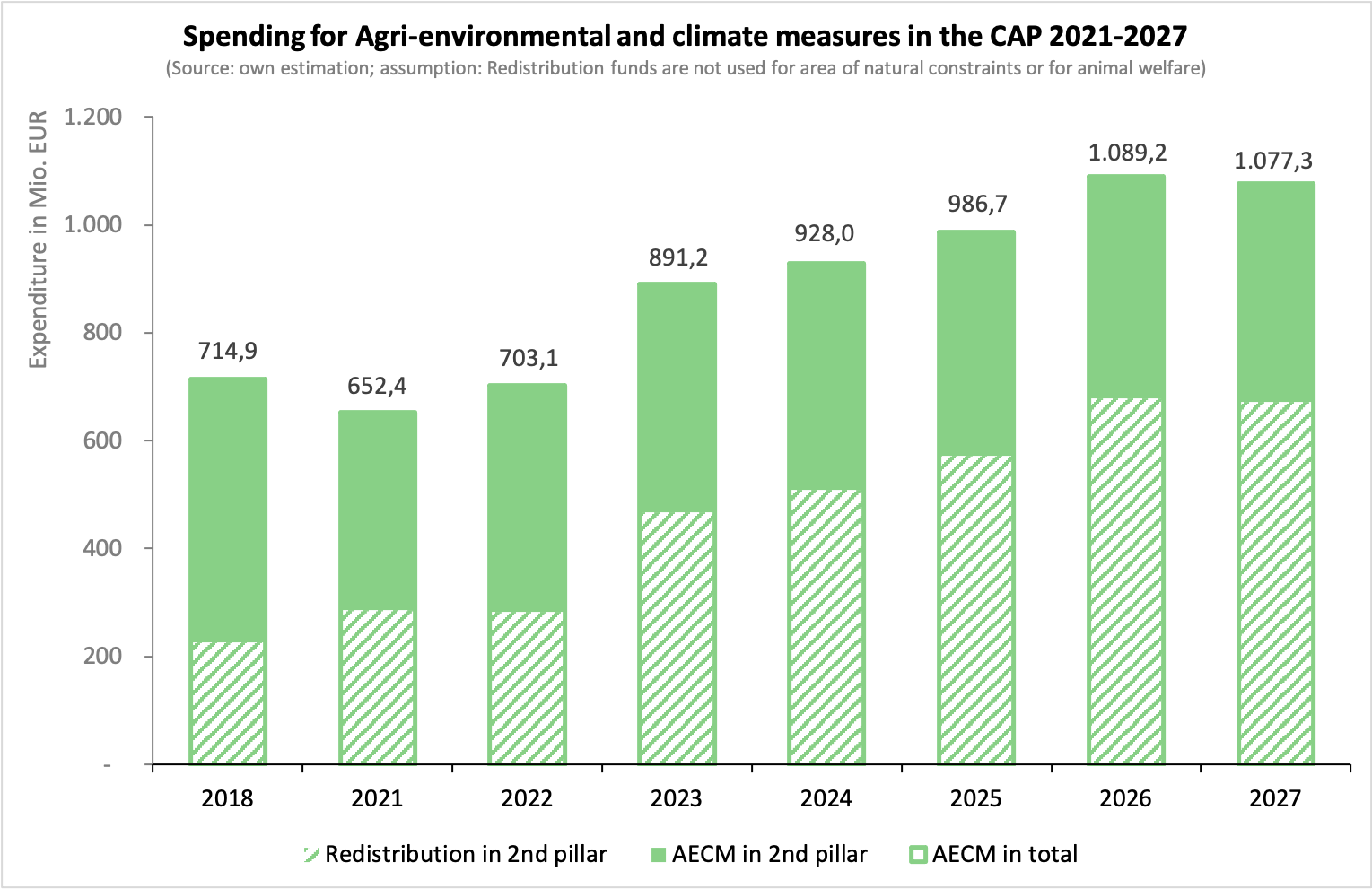

This result is still more favourable than most of the previously assumed scenarios. Only the two quite optimistic scenarios of Parliament and Council provide similar amounts for environmental measures with ca. € 1.9 billion EUR. In this respect, one can describe these resolutions as a step in the right direction in terms of environmental spending. Getting more into the details, we can observe, that especially the payments for agri-environmental and climate measures can be extended. If we assume, that the reallocation into the 2nd pillar is used for AECM, then much more funds are available for AECM, increasing from the 2018 level of € 715 Mio to ca. € 1,000 Mio from 2026 onwards. (Note, that in many evaluations, AECM show different degrees of effectiveness, however, at least some of the measures are quite effective.). Especially this aspect of the German implementation can open the door for a more effective environmental policy, but here as well, the devil lies in the detail and finally, it depends, whether reallocation-funds are used for AECM or spent for ANC or animal welfare.

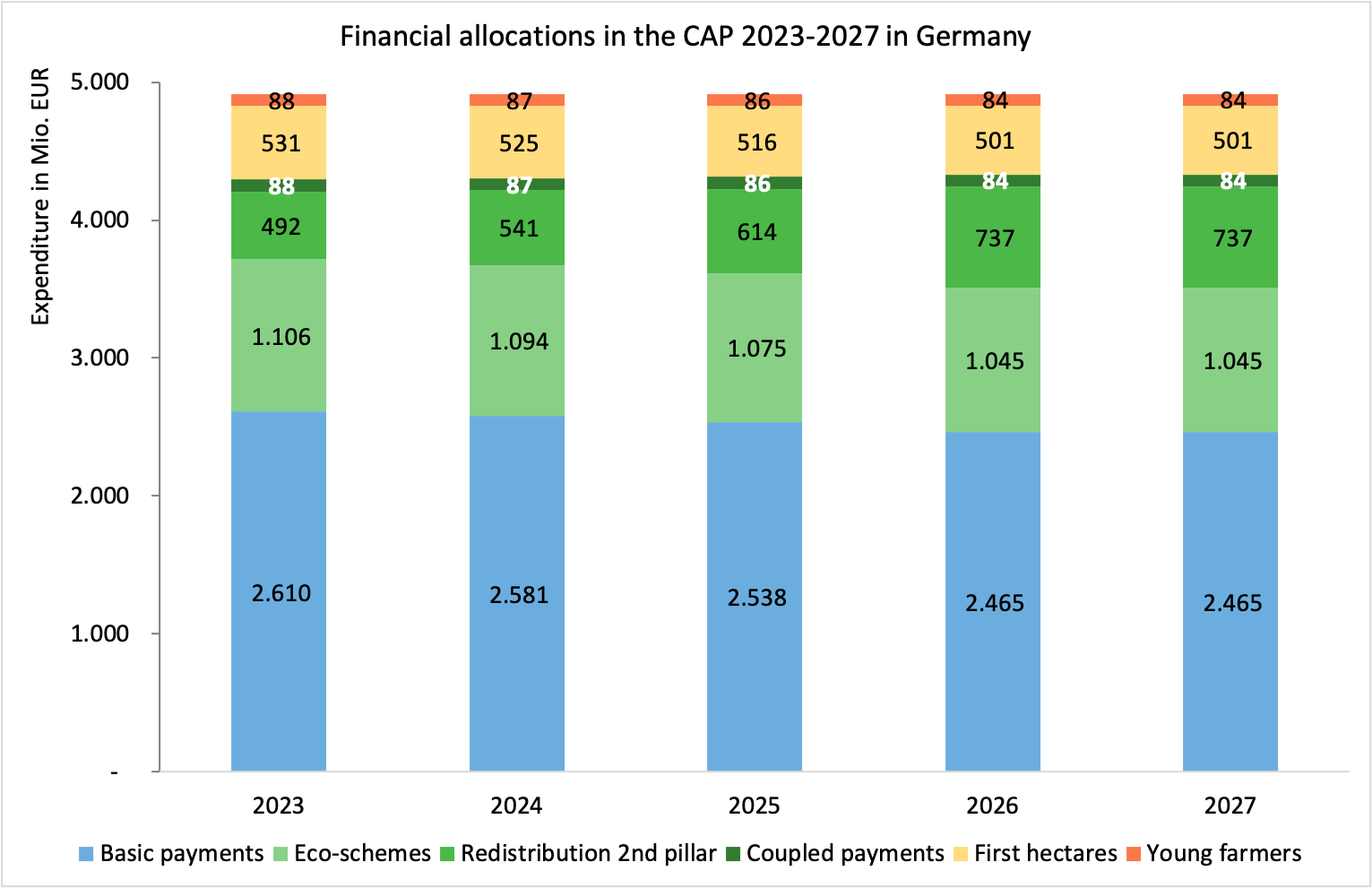

A side-effect of the increasing reallocation from 2023 is that the funds for direct payments will be gradually reduced. The following figure shows the step-by-step lowering of the basic premium, which will initially be 150 EUR / ha in 2023, but then drop to 135 EUR / ha. This transition makes sense because it describes a development path and farms can adjust to the changes over several years (see next figure).

In the first year of the CAP implementation in 2023 around 61% will still be used for the basic premium and redistribution, but this will decrease to 56% by 2027. If one assumes that the Small Farmers Scheme and the young farmers’ payments are social goals (which one can also discuss…), then by the end of the next funding period almost 44% of the payments will be oriented towards social goals. However, the weak points have already been identified (payments for areas of natural constraints (ANC)). The young farmers’ payment also seems to have been little reflected upon, because when a farm is taken over, investment projects are sooner to be befitting rather than a (fairly low) area payment. In this respect, it would make sense to discuss other instruments and methods for this measure as well.

9. Open Points

Overall, the decisions of the AMK point in the right direction. But none of the measures has already been worked out in such a way that a final assessment can be made.

- Conditionality: As outlined above, conditionality is still being worked out and the AMK and the BMEL will (blindly?) adopt the resolutions of the trilogue. From a competition policy perspective this may seem sensible, since the same law applies to all member states. On the other hand, uniform clauses can be interpreted differently in the member states. In this manner, peatlands and wet grassland are classified as grassland in some German federal states (e.g. Bavaria), so that farms can receive direct payments, while other federal states do not define such areas as grassland, and peatland protection fails because there are no direct payments. This heterogeneity is also likely to develop between the member states, so the AMK decision is not convincing.

- The details of eco-scheme measures have not yet been negotiated. The effectiveness of a crop rotation support depends on which crops are prescribed and in which proportion. The AMK resolution says nothing about this, and the details of other measures still have to be worked out. The tightrope walk runs between measures that are, on the one hand, sufficiently simple for many farmers to share, and sufficiently specific that they have an effect. Finding this balance will be the task of the BMEL; effectiveness depends on this.

- The payment levels for different eco-schemes are not yet fixed. Here, too, a lot depends on whether the eco-schemes use tax resources efficiently. There have been several calls for agri-environmental measures to include an income component. The first question will be whether such a component is used systematically in both pillars or only in the eco-schemes (which is not advisable). The second question, which has been discussed for years, deals with the subject of the WTO criteria: If agri-environmental measures are to be “green box compliant”, they must not be linked to production. However, this is simply necessary for certain measures. The EU Commission has set this requirement without considering that it unnecessarily restricts the funding of certain measures. Part of the funding could simply be reported as an amber box, since there is still room for manoeuvre here. The blog post by Norbert Röder on CAP reform from 02.03.2021 provides an overview of the debate. Overall, a lot depends on the structure of the premiums, and eco-schemes can be a success in combination with the AECM, or continue the problems of greening.

- Finally, the programming of the agri-environmental and climate measures is still missing in the second pillar, which is implemented by the federal states and which will make a decisive contribution to whether the CAP reform brings an improvement or not. The federal states have the tricky task of programming the measures in such a way that they are compatible with the previous measures and, on the other hand, fit with the eco-schemes. It is probably irrelevant to farm managers whether a measure is offered in pillar I or II; what matters more is whether the measures can be combined and whether different contracts with different specifications and control times are concluded so that measures entail a high administrative and control effort. In 2019, the Scientific Advisory Board at the BMEL has published a report on the subject of administrative simplification (in English). I actually mention this report in every second blog post hoping that it will be read and implemented by the ministries. The farm managers would certainly appreciate some degree of simplification.

10. Conclusions

The decisions of the AMK are going in the right direction, but the most important details have not yet been finalised. Actually, the decision is a success of the agriculture ministers of the Green Party. 8 of 16 agricultural ministers are from the Green Party, which suggests a certain influence. In the past, it was difficult to see a coordinated policy impact, however this time, they had apparently better prepared. But also, agriculture ministers from other parties supported the change requests and supported the more ambitious course. In the medium term, it remains to be seen whether the BMEL and the state ministries will make something out of this proposal. The door for a more ambitious CAP is open, but the federal and state governments still have to go through it.

A version of this article was originally published in German on Sebastian Lackner’s blog

This article is produced in cooperation with the

This article is produced in cooperation with the

Heinrich Böll Stiftung European Union.

More by Sebastian Lackner

Is Food Security A Relevant Argument Against Environmental Measures In The EU?

More on CAP Strategic Plans

CAP Strategic Plans: Support to High-Nature-Value Farming in Bulgaria

Commission’s Recommendations to CAP Strategic Plans: Glitters or Gold?

German Environment Ministry Proposals For CAP Green Architecture

CAP Performance Monitoring and Evaluation Framework – EP Position

A Rural Proofed CAP post 2020? – Analysis of the European Parliament’s Position

CAP Beyond the EU: The Case of Honduran Banana Supply Chains

CAP | Parliament’s Political Groups Make Moves as Committee System Breaks Down

CAP & the Global South: National Strategic Plans – a Step Backwards?

CAP Strategic Plans on Climate, Environment – Ever Decreasing Circles

European Green Deal | Revving Up For CAP Reform, Or More Hot Air?

Climate and environmentally ambitious CAP Strategic Plans: Based on what exactly?

How Transparent and Inclusive is the Design Process of the National CAP Strategic Plans?