By Guus Geurts

Why has the CAP been historically problematic for farmers’ economic sustainability, biodiversity and the environment, in the EU and the Global South? This two-part series underlines the crucial role of trade policies in shaping agriculture. In this first article, I explore historical choices regarding trade and CAP that led our agriculture towards liberalisation, highlight the consequences and propose some changes that could start a shift away from a market-oriented agriculture. A second article will then focus on the Farm to Fork Strategy, its potential and the changes needed in trade and CAP policy to make it effective, coherent and fair for farmers inside and outside the EU.

I would like to thank Niek Koning and Gérard Choplin for their very useful comments.

Introduction

Since 1992, the WTO-ruled CAP has shown a lot of limits in addressing economic sustainability for farmers as well as environmental challenges, inside and outside the EU. Market regulations have been replaced by unstable low prices compensated by hectare-based subsidies, following a logic of liberalisation of food systems. Last year’s reform could have been an opportunity to change the WTO logic behind the CAP and address the worldwide negative effects it has had on the livelihoods of family farmers, the environment and food security. This opportunity has been missed. But how did we end up in this unstable and precarious situation in the first place?

Historical analysis[1]

1962 – 1992: Decades of market intervention

The objectives of the Common Agricultural Policy, established by the predecessor of the EU in 1962 remained unchanged since the Treaty of Rome came into force in 1958. The five key objectives were:

- To increase agricultural productivity;

- To ensure a fair standard of living for farmers;

- To stabilise markets;

- To ensure the availability of food supplies;

- To ensure reasonable prices for consumers.

To reach these goals while staying in the frame of the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT), countries were allowed to protect their agricultural markets, provided that they controlled their production and exports. In order to protect agricultural markets, the main measures implemented were the introduction of import tariffs and import quotas as well as the implementation of minimum intervention prices in land bound sectors like dairy, beef, grains and sugar. The EU intervened in the market if prices fell too low, for example with commodity storage.

The CAP was successful in building agricultural self-sufficiency in Europe[2]. But by aligning guaranteed prices with the level of the lowest costs of production, the CAP also induced a quick industrialisation of production and many farmers had to leave agriculture. With minimum prices, increased intensification, and a lack of supply management, mountains of surpluses (milk powder, butter, beef, sugar and cereals) started to pile up. In order to get rid of those surpluses, export subsidies were introduced, covering the difference between the prices paid to farmers and the world market priceexs. This dumping of food on international markets especially affected farmers in the Global South. It also led the CAP budget to rise and as a result, supply management was introduced through the quota system with the milk quotas established in 1984. However, because the quotas permitted exceedance by 10% of total EU consumption, a lot of room was still left for subsidised export.

From 1992 onwards, a WTO-ruled CAP

In 1992, in the build-up to the WTO Agreement on Agriculture (AoA), and in cooperation with the US, the EU decided to tackle the increasing CAP budget and answer critics of dumping. The AoA and the 1992 CAP-reform reorganised the way EU would accommodate to market rules.

The AoA decreed that WTO members had to reduce by certain percentages all protective market measures, which means lowering import taxes. Both the EU and US had to drastically decrease their safety buffer stocks for grains. Looking at it through the lens of the current food crisis, those stocks would have been useful to prevent price peaks and speculation[3]. Least developed countries were exempted from those obligations, but they already faced forced liberalisation of their markets through Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) led by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund[4]. This had a devastating effect on farmers and food security in the Global South[5].

From the 1992 CAP-reform onwards, instead of effectively managing supply, the EU decided to lower guaranteed prices, aligning them with world prices. As these new prices were too low for European farmers, the EU partially compensated them with direct payments. With the EU maintaining its export ambitions, these payments essentially replaced the former export subsidies. Dumping in third countries goes on, but is not recognised as such by the WTO rules anymore. That is the trick of the AoA[6] – the WTO recognising dumping as an export below the internal price and not below the costs of production. In the end, it mainly served the interests of (multinational) agribusinesses that needed new markets to dispose of the EU overproduction for a cheap price.

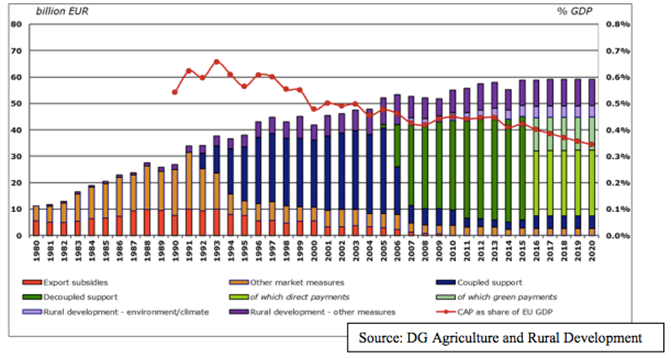

Those decisions reshaped the way European agriculture was subsidised but didn’t allow for the budget to decrease. Reduced expenses for intervention stocks and export subsidies were counterbalanced by the amount of direct payments, first through coupled support, later through decoupled support.

Reforms in trade policy and CAP since 2001

Since 2001, the WTO negotiations in agriculture have been stalled and the Global South has kept on criticising the use of trade distortion subsidies. The US recently attacked India’s subsidy programme for food and agriculture, aimed at insuring food access for the poor and fair revenues for farmer[7]. Professor Biswajit Dhar, Head of the Centre for WTO Studies at the Indian Institute of Foreign Trade, explained that “developed countries like the US and EU subsidise agriculture to exploit global markets while India and other developing countries use subsidies and public food stocking to ensure domestic food security and livelihoods.”

Meanwhile the EU moved the attention to bilateral and regional free trade agreements (FTAs) such as Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) with the African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP)-countries

(former colonies), Canada (CETA) and Mercosur. Within EPAs, the EU pushed developing countries to liberalise most of their agricultural and industrial sector, leading to loss of livelihood for farmers. The dumping of skimmed milk powder, re-fattened with imported palm oil in Western Africa, is an example of how those trade agreements can destroy third countries agricultural sectors. Adama Diallo, chair of the national union for mini-dairies and local milk producers in Burkina Faso, explained that “this imported milk powder is a lot cheaper than local milk and therefore kills off local production”. Implementation of EPAs would only increase this issue as they would “give way to a 0% tax import on European milk products, which are already only taxed at 5%”[8]

Another important reason for this increased dumping is the abolishment of the EU milk quota system in 2015. Quickly increasing production led to a dramatic price drop, that could only be partially covered by direct payments. Arable farmers also lost part of their income since 2017 when the abolishment of the EU sugar quota system led to a price drop[9].

To cover up the promise that subsidies were not trade distorting, from 2014 onwards, all European farmers get a direct payment per hectare. Since 2003, the EU is also legitimising those subsidies through environmental conditionality. But, as the European Court of Auditors concluded, the CAP “hasn’t been effective in reversing the decades-long decline in biodiversity and intensive farming remains a main cause of biodiversity loss” with an estimated 1.000 farms disappearing every day.

Current role of the Common Market Organisation (CMO)

The CMO is the legal framework for market measures provided under the CAP, covering all agricultural products. As we’ve discussed, through different reforms, the policy progressively became more market-oriented, scaling down the role of intervention tools, which are now regarded as safety nets to be used in the event of a crisis[10], the latest example being the pig meat sector support measures. During the last decades, the CAP shifted from CMO rules (import duties, export refunds, etc.) to mostly direct payments. Export refunds and most of the supply control measures have been abolished but direct payments coupled and later decoupled, still lead to exporting below the cost of production.

Currently, import duties and tariff quotas are still in place. Tariff quotas are import quotas in certain commodities for which zero import duties are imposed. However, because of various FTAs (with Canada, Mercosur, Australia, New Zealand, etc.), import duties are reduced to zero and tariff quotas are increased. Public storage systems coupled with minimum intervention prices have also been reformed drastically. Opportunities for public intervention or private storage aid still exist, but are more restricted.

Propositions to reach an effective CAP and CMO

During the last CAP negotiations, both the Committee of Regions and the European Parliament made propositions to amend the CAP and CMO and address the issues that we’ve discussed. They insist that while ensuring stable livelihoods to European farmers, the EU should also meet the UN Sustainable Development Goals and EU’s policy coherence for development. To do so, the CAP should promote the development of sustainable and prosperous family farming in developing countries, which helps maintain rural populations and ensures the security of their food supplies. To reach this goal, I highlight here below some proposed changes that would be crucial to create a robust framework ensuring robust regulated markets :

- EU agricultural and food products should not be exported at prices below European production costs.

- Member States should include interventions for crisis prevention and risk management in every sector of their strategic plans.

Where the market prices fall below a certain flexible threshold that is indexed to average production costs and set by the European market observatory for the sector concerned, the European Commission shall implement support measures for producers in the sector concerned who, over a specified period, voluntarily reduce their deliveries compared to the same period in the previous year. The current volume reduction scheme, granting aid to dairy farmers who voluntarily produce less in times of severe market imbalances, should be extended to all agricultural sectors. Later on, those schemes should evolve by permitting obligatory cuts when crises worsen. The European Milk Board has already developed a Market Responsibility Programme proposing voluntary reductions in milk production in case of a price crisis, followed by obligatory cuts if necessary.

- The list of products eligible for public intervention should be extended to new products: white sugar, sheep meat, pig meat and chicken. Public intervention should be open for all eligible products throughout the whole year, not only for specified periods.

- In order to maintain fair competition and ensure reciprocity, the EU should enforce production standards consistent with those established for its own producers. Import of agri-food products from third countries should only be allowed if they comply with standards and obligations applying to the same products in the EU, in particular in the field of environmental and health protection.

Introduction to part 2

First of all, even though these are good proposals, they mostly didn’t make it to the final CAP text or are not yet part of the multilateral trade policy. Moreover, some environmental measures such as the reciprocity of norms induce questioning on effects that they could have on third countries and their compliance with WTO rules. In the second part of this series, I will focus on the Farm to Fork Strategy and, building on the above proposals, highlight the changes that would be needed in trade policy and CAP to make them effective and fair to farmers, the environment and food security inside and outside the EU.

Guus Geurts studied Environmental Policy, is a publisher (author, photographer of World Food – Pledge for a Just and Environmental Friendly Food Supply (Dutch)), and campaigner in EU agriculture and trade policy. He is the coordinator of the Agriculture coalition for Just Trade (farmers’ organizations) and is involved with the Platform Aarde Boer Consument, Voedsel Anders NL, the Handel Anders!- the coalition and Working group Food Justice (all established in the Netherlands) and the (international) Seattle to Brussels network.

Guus Geurts studied Environmental Policy, is a publisher (author, photographer of World Food – Pledge for a Just and Environmental Friendly Food Supply (Dutch)), and campaigner in EU agriculture and trade policy. He is the coordinator of the Agriculture coalition for Just Trade (farmers’ organizations) and is involved with the Platform Aarde Boer Consument, Voedsel Anders NL, the Handel Anders!- the coalition and Working group Food Justice (all established in the Netherlands) and the (international) Seattle to Brussels network.

→ Read part 2 of the “A Just and Green CAP and Trade Policy in and Beyond the EU” series here.

[1] https://www.rli.nl/sites/default/files/infographic_1_-_veranderingen_europees_landbouwbeleid_in_vogelvlucht.png and https://slideplayer.com/slide/13041189/

[2] Exceptions to this are vegetable protein and oils. In 1962 the US forced the EU to lower import tariffs to zero on oil-seeds/cakes (mainly soy) and grain substitutes such as maize gluten. Import tariffs on soy are still zero.

[3] https://www.sol-asso.fr/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Rebuilding-the-WTO-for-a-sustainable-global-development-J.-Berthelot-July-12-2020.pdf

[4] https://www.boerengroep.nl/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Koning-2006.-Agriculture-development-and-international-trade.-CAP-and-EU.pdf

[5] https://grain.org/fr/article/entries/212-trade- and https://www.iatp.org/sites/default/files/Food_Sovereignty_in_the_Era_of_Trade_Liberaliz.htm

[6] https://www.sol-asso.fr/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/Rebuilding-the-Agreement-on-Agriculture-on-food-sovereignt.pdf

[7] https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/us-stand-at-wto-on-india-s-msp-to-farmers-erroneous-says-trade-expert-118093000212_1.html

[8] https://www.politico.eu/article/hogans-milk-wars/

[9] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/108/first-pillar-of-the-cap-i-common-organisation-of-the-markets-cmo-in-agricultural

[10] https://www.agriculture-strategies.eu/en/2019/07/the-european-sugar-policy-a-policy-to-rebuild/

Download this article as a PDF

This article is produced in cooperation with the

This article is produced in cooperation with the

Heinrich Böll Stiftung European Union.

More on CAP Strategic Plans

Bulgaria’s CAP Strategic Plan: Backsliding on Nature and Biodiversity

Changes “required” to Ireland’s CAP Strategic Plan – European Commission

French CAP Plan: What Opportunities for Change During the New 2022-27 Presidential Term?

CAP, Fairness and the Merits of a Unique Beneficiary Code – Matteo Metta on Ireland’s Draft Plan

ARC Launches New Report on CAP as Member States Submit Strategic Plans

Slashing Space for Nature? Ireland Backsliding on CAP basics

Quality Schemes – Who Benefits? Central America, Coffee and the EU

Civil Society Organisations Demand Open and Ambitious Approval of CAP Plans

CAP Strategic Plans: Germany Taking Steps in the Right Direction?

CAP Strategic Plans: Support to High-Nature-Value Farming in Bulgaria

Commission’s Recommendations to CAP Strategic Plans: Glitters or Gold?

German Environment Ministry Proposals For CAP Green Architecture

CAP Performance Monitoring and Evaluation Framework – EP Position

A Rural Proofed CAP post 2020? – Analysis of the European Parliament’s Position

CAP Beyond the EU: The Case of Honduran Banana Supply Chains

CAP | Parliament’s Political Groups Make Moves as Committee System Breaks Down

CAP & the Global South: National Strategic Plans – a Step Backwards?

CAP Strategic Plans on Climate, Environment – Ever Decreasing Circles

European Green Deal | Revving Up For CAP Reform, Or More Hot Air?

Climate and environmentally ambitious CAP Strategic Plans: Based on what exactly?

How Transparent and Inclusive is the Design Process of the National CAP Strategic Plans?